The Economic Risks of Transposing the EU Product Liability Directive in Germany

Published By: Oscar Guinea Dyuti Pandya Vanika Sharma

Research Areas: EU Single Market, Institutions, and Governance Industrial and Competitiveness Policy

Summary

With the Ministerial Draft (Referentenentwurf) dated 11 September 2025, Germany has embarked on transposing the EU Product Liability Directive (EU PLD) into national law, a step that goes beyond a mere regulatory update and could have far-reaching implications for its economic competitiveness.

The most immediate impact will be felt within Germany’s Information and Communication Technology (ICT) industry, which stands as one of the largest in Europe. The Ministerial Draft broadens the definition of a “product” to include software, digital files, and services like AI systems, exposing ICT firms to greater liability risks. As companies prepare to minimise the risk of liability issues, compliance procedures will intensify, leading to higher operational costs. Furthermore, in some cases, the Ministerial Draft overlaps with existing regulations which fuels legal uncertainty and discourages innovation.

Beyond the ICT industry, the Ministerial Draft poses risks to Germany’s broader manufacturing base. As digital technologies become increasingly embedded in the manufacturing process, any disruption in the ICT sector will directly affect other industries such as the automotive and medical technology sectors. The implementation of the Ministerial Draft in Germany’s new Product Liability Act may slow digital adoption and make the integration of these technologies more costly, ultimately hampering Germany’s industrial competitiveness.

Critically, the Ministerial Draft significantly increases the likelihood of collective actions. By expanding liability to a wider pool of companies – including component suppliers, service providers, and even app developers – the Ministerial Draft amplifies the risk of mass litigation. In addition, both the previous deductible for property damage and the overall liability cap are eliminated. Moreover, the introduction of rebuttable presumptions of defectiveness which significantly lowers the bar for claimants, together with the introduction of evidence disclosure obligations – a notable procedural departure for German law – increases the potential for costly and time-consuming legal battles.

To assess these costs, this Occasional Paper draws on empirical evidence from the US, where mass litigation has long been a challenge, to estimate the impact of collective actions on the German economy. While the implementation of EU PLD may not be the sole driver of increased mass litigation in Germany, it is undeniable that it will contribute to this trend. The presence of a well-developed ecosystem of lawyers, litigation funders and claims collectors – combined with a broader regulatory trend facilitating mass litigation in Germany, exemplified by the Consumer Rights Enforcement Act (VDuG) and its representative action mechanisms – makes the rise of representative- and collective actions a tangible economic risk.

The economic costs of mass litigation are significant. Private enforcement costs, litigation expenses, and the potential slowdown of innovation all add up. The total cost could amount to billions of euros annually, with the risk of mass litigation diminishing the market value of innovative firms by as much as €10 billion. Such disruptions not only affect businesses but could also impact the wealth of German families, as pension funds and insurance portfolios are tied to the performance of these companies.

The implementation of EU PLD may slow down Germany’s digitalisation efforts which would have an impact on the wider economy as ICT has become a cornerstone of Germany’s economic growth, and its role in the wider manufacturing sector is indispensable. The government has made strides to reduce bureaucracy and enhance competitiveness, but the Ministerial Draft may undermine these efforts by adding regulatory complexity and heightening legal risks. Policymakers must carefully weigh these economic consequences when they decide on how exactly they will transpose the EU PLD to avoid unintended setbacks that could hinder Germany’s future economic growth.

1. Introduction

With the Ministerial Draft,[1] Germany has begun transposing the revised EU Product Liability Directive. This is far more than a technical update to the 1989 German Product Liability Act; it represents a fundamental recalibration of liability for the digital age, with wide-ranging implications for companies.

The Ministerial Draft treats digital and non-digital sectors equally. Yet in doing so it assumes, wrongly, that they can be regulated in the same way. Digital products are inherently different from physical goods: they evolve over time, receiving updates from both manufacturers and adapting to users’ behaviours. This makes assigning liability across sellers, producers, and component makers far more complex.

As a result of the implementation of the Ministerial Draft in Germany’s intended new Product Liability Act, digital firms will need to record every interaction with suppliers and customers to protect themselves against potential liability. At the same time, the innovative nature of digital products, which often requires several iterations after release,[2] could be hindered if courts interpret these improvements as evidence that the original version was flawed.

The economic consequences are significant. As Europe’s largest software market, with nearly 100,000 IT firms, Germany’s ICT sector faces significant setbacks if regulatory uncertainty and new legal risks proliferate across the industry.[3] The second impact is on Germany’s industrial base. Regulatory burdens on ICT will spill over into manufacturing, slowing digital adoption and increasing costs. These effects run counter to the government’s efforts to support industrial digital transformation through Industry 4.0 programmes and new innovation frameworks[4] – the term “transformation” appears 42 times in the coalition agreement.[5]

Germany can ill afford these setbacks. With a stuttering economy, policymakers are focused on cutting bureaucracy,[6] easing regulatory burdens[7] and boosting competitiveness.[8] Modern applications in autonomous driving, e-health, or precision agriculture depend on high-performance digital infrastructure and digital products. Yet the implementation of the Ministerial Draft, in its current form, in Germany’s new Product Liability Act may work against this agenda by adding red tape rather than simplifying regulation. Germany should consider carefully how it can transpose the EU PLD while ensuring that any negative consequences are minimised as far as possible.

The Ministerial Draft explanatory memorandum acknowledges some costs, largely administrative and borne by the state. Total costs are likely to be higher. Extending liability across digital supply chains increases the risk of collective actions against multiple suppliers. Germany already has a highly developed ecosystem for bringing mass claims that involves litigation funders, claim-collection firms, and legal insurance providers. While procedural safeguards limit how damages can be pursued and a ceiling applies to the percentage that litigation funders may earn, the expansion of liability to digital products could still encourage mass litigation. Digital products, which can affect thousands of users simultaneously, are natural targets for such actions.

Faced with this threat, companies will ramp up compliance far beyond what the government anticipates. Moreover, the economic literature is clear in relation to the cost of mass litigation. Growth in collective actions means higher litigation costs, greater enforcement burdens and weaker innovation across the economy.

This Occasional Paper sets out the potential economic risks of transposing the EU PLD in Germany, with particular attention to the likely rise in collective actions. It is structured as follows:

- Chapter 2 examines the main features of the Ministerial Draft, including how it defines product, defect and damage, expands liability across supply chains and over time, and effectively shifts the burden of proof.

- Chapter 3 analyses how these developments could make mass litigation more common in Germany.

- Chapter 4 reviews lessons from mass litigation in non-digital sectors.

- Chapter 5 argues that the implementation of the Ministerial Draft in Germany’s new Product Liability Act risks shifting the costs of mass litigation into Germany’s digital sector, undermining Germany’s economic competitiveness.

- Chapter 6 assesses the wider economic impact of increased mass litigation and shows why costs are likely to exceed official estimates.

- Chapter 7 presents the key conclusions from the study.

[1] Ministerial Draft (Referentenentwurf) of the Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection dated 11 September 2025. Available at: https://www.bmjv.de/SharedDocs/Gesetzgebungsverfahren/DE/2025_Produkthaftung.html

[2] Software updates are not required because the original version is inherently faulty, but because they are an essential part of maintaining and improving technology over time. Updates help sustain system performance, protect against emerging security threats, enhance stability, and ensure compatibility with new applications.

[3] ITA. Germany Country Commercial Guide. Available at: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/germany-information-and-communications-technology-ict

[4] Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action. (2025). Manufacturing-X – Funding Scheme for a Competitive, Resilient and Sustainable Industry. Available at: https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/EN/Publikationen/Digitale-Welt/manufacturing-x-program.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6l

[5] Federal Government. Coalition Agreement. Available at: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/federal-government/coalition-agreement-482268

[6] Die Bundesregierung. (2025, July 30). Tailwind for state modernization and bureaucracy reduction. Available at: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/aktuelles/ausschuss-staatsmodernisierung-2373828

[7] One of the initiatives include the Act to strengthen growth opportunities, investment and innovation as well as tax simplification and tax fairness (Growth Opportunities Act). Federal Law Gazette 2024 I No. 108 from March 27, 2024.

[8] Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action. (2025). Annual Economic Report. Available at: https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/EN/Publikationen/Wirtschaft/annual-economic-report-2025.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4

2. The New German Product Liability Law

2.1 Rethinking Product, Defect, and Damage in the Digital Age

One of the most significant aspects of the Ministerial Draft is the expanded definition of a product, which now explicitly includes digital manufacturing files and software under Section 2. Moreover, the Ministerial Draft’s explanatory memorandum explains that software will fall under product liability regardless of how it is supplied or used, whether embedded in a physical product, connected to one, stored locally on a device, or accessed through the cloud.

The modernisation of the product liability law also considers other factors when assessing defect such as the product’s self-learning capabilities (e.g., machine learning), its interactions with other products (e.g., traffic data used by the navigation system of an autonomous vehicle), and compliance with cybersecurity requirements. In a significant development, damages caused by the destruction or loss of data not used for professional purposes are also eligible for compensation.

However, implementing the current regulatory framework in the digital economy faces some difficulties. Autonomous vehicles provide a good illustration. Under current German law, liability for damages in road traffic is primarily governed by the Road Traffic Act (StVG), which already establishes strict liability and liability for negligence for manufacturers, and, since the 2017 amendment, extends this to highly and fully automated driving functions.[1]

The German transposition of the EU PLD goes further than the StVG by explicitly extending strict liability to digital components integrated into a product, such as navigation systems or software updates. This results in two parallel liability regimes: one under the general traffic liability and insurance rules (e.g., the StVG) and another under the new PLD-based framework. While claimants cannot obtain double recovery for the same damage and must ultimately choose their legal basis, the coexistence of these regimes creates legal and procedural uncertainty for both victims and manufacturers.

This regulatory uncertainty directly increases compliance costs that are already onerous in the EU. In digital products, especially, including AI, it is particularly difficult and often unclear to prove whether a harm has occurred because of a genuine defect in the product, from misuse by the consumer, from interference by a third party, or from the autonomous behaviour of the AI system itself. This is because, in contrast to traditional goods, these technologies are adaptive and dynamic. Their decision-making processes can evolve in ways that were not foreseen at the moment of design or production.

Therefore, in order to manage overlapping liability risks, companies producing and using these technologies will be required to invest in more extensive documentation, testing, and risk monitoring not only for the initial version of a product, but also for subsequent updates, retraining cycles, or changes in system behaviour. And even with rigorous compliance measures, tightened security protocols, and regular checks, establishing a clear causal link between a defect in a product and the harm (e.g., loss of data) will always be difficult, especially in a setting in which multiple inter-acting products are used such as in hospitals.

Even more significantly, an unchecked transposition of the EU PLD may discourage or delay the introduction of new or improved products in Germany. From an engineering perspective, iterative improvement is a natural and responsible part of product development; however, such changes may be presented as evidence of defectiveness, even though they are improvements, making it easier for claimants to argue liability. While the Ministerial Draft seeks to limit this risk by clarifying that a product is not defective merely because a better version exists, in practice, the line between responsible innovation and evidence of defectiveness may remain unclear.

The difficulty lies in the fact that the test for defectiveness is tied to a product’s safety, rather than its fitness for purpose. Under Section 7, a product is deemed defective if it fails to provide the level of safety that people are entitled to expect, or that is required under EU or national law. Section 8 adds that all relevant circumstances must be considered, including a product’s ability to learn or acquire new functions after being placed on the market, as well as the foreseeable effects of other products expected to interact with it. This creates a risk for firms: when they update or improve a product, even to enhance safety, such changes could be cited in court as evidence that the earlier version was unsafe. As a result, companies may think twice before innovating or rolling out improvements.[2]

2.2 Expanded Liability Across the Supply Chain and Throughout the Product Lifecycle

The proposed new product liability law in Germany would widen the scope of responsibility by defining “economic operator” (Sections 3, 4 and 10–11) to include not only manufacturers but also component makers, service providers, authorised representatives, importers, fulfilment providers and distributors. Anyone who develops, manufactures, designs or commissions a product may now be held jointly and severally liable (Section 15).

This wider scope is particularly challenging in the digital economy. A product’s functionality often depends on software developers, component suppliers, integrators, cloud providers, platform operators and even end-users. In such fragmented ecosystems, as mentioned previously, assigning fault is far harder than under the traditional producer-centred liability model.

Two provisions create additional uncertainty. First, anyone who affixes their name, brand or other mark to a product may be treated as a manufacturer (Section 3). This could expose resellers, distributors or firms that simply rebrand or white-label goods to the same liability as producers. In the digital context, the scope is even less clear: software branding, app-store listings or digital signatures may all trigger manufacturer status. Second, the Ministerial Draft recognises that many products remain under the manufacturer’s control even after sale, through updates, remote access or cloud-based functions. Liability, therefore, extends for as long as the manufacturer retains such control.

The Ministerial Draft proposes a series of successive deadlines for bringing claims. Under Section 16, the standard limitation period is three years from the moment the injured person becomes aware, or ought to have become aware, of the product defect, the damage and the identity of the debtor. Section 17(1) adds a ten-year absolute cut-off from the date the product was placed on the market or put into service, after which claims cannot be made (this does not apply if the creditor has initiated proceedings against the debtor before the expiry of the 10 years limitation period). An exception applies to latent health injuries: where medical evidence shows symptoms only emerge after a long delay, and the limit is therefore extended to a lengthy 25 years (Section 17(3)).

This lifecycle view creates particular problems for AI-driven systems. As mentioned, unlike traditional goods, they do not simply wear out; they evolve through updates, new data and integration with other services. Risks may appear years after sale, for example, through later updates or compatibility issues arising as surrounding systems evolve more rapidly than the product can be updated. Proving causation over such timeframes presents significant evidentiary challenges for claimants. As explained in the next section, the EU PLD sought to address this by introducing presumptions of defect and causation in certain circumstances, effectively lowering the burden for claimants but simultaneously increasing potential exposure for manufacturers. However, this approach may have limited practical effect in complex digital ecosystems, where evidence is already difficult to trace and attribute. After ten or twenty-five years, records may be incomplete, forensic traces lost, or the original manufacturer no longer in business, making it doubtful whether such presumptions can meaningfully assist in establishing causation.

2.3 Effectively Shift in the Burden of Proof and Disclosure Rules

The EU PLD makes it easier for claimants to prove their case by introducing rebuttable presumptions – i.e., legal assumptions which stand unless the defendant can disprove them. These presumptions apply in several situations including where showing that a product was defective, or that it caused the harm, would otherwise be very difficult because of the product’s technical or scientific complexity. In such cases, the claimant only needs to show that a defect or causal link is probable.

The EU PLD also establishes two specific presumptions of defectiveness in case of litigation. The first applies when a defendant refuses to comply with a court order to disclose evidence, thereby blocking the claimant’s ability to prove their case. The second applies when the claimant can show that the product failed to meet mandatory safety requirements under EU or national law, or that the harm resulted from an obvious malfunction during normal or foreseeable use.

Sections 19 and 20 of the intended new German product liability law adopt these presumptions. While Recital 43 of the EU PLD explicitly gives member states the discretion to stipulate rules on disclosure obligations not regulated by the Directive, the Ministerial Draft does not provide for pre-trial disclosure, disclosure by third parties, or penalties for failing to comply with disclosure orders. Notably, the Ministerial Draft relies on the vague legal terms found in the EU PLD – including the “plausibility” threshold of the claimant’s damages claims as a trigger for disclosure. Especially, the Ministerial Draft limits disclosure to what is “necessary and proportionate” but largely fails to provide concrete definitions or robust safeguards. Without clear criteria, courts are left with broad discretion, and parties cannot reliably predict the scope of disclosure they may be compelled to provide. This vagueness creates serious risks: disclosure requests could be used strategically by claimants to impose disproportionate costs or pressure defendants into settlement.

However, the intended new rules are far more favourable to claimants than what is available to them under current German law. In accordance with the EU PLD, Section 20(1) presumes a product is defective if a defendant fails to disclose relevant evidence. Section 20(2) extends this presumption to causation where the damage is typical of the defect. Section 20(3) allows courts to presume defectiveness or causation or both even when disclosure has been made, if the claimant shows that proof remains excessively difficult due to technical or scientific complexity and that a sufficient likelihood exists that the product is defective, that there is a causal link between the defect and the injury, or both. These increasingly favourable rules are leveraged by the fact that with the introduction of terms such as “causal link” and “excessive difficulty” the draft law introduces undefined legal terms which add an additional element of legal uncertainty.

At the same time, the disclosure mechanism that underpins these presumptions is far from straightforward in practice. Disclosure obligations raise significant practical challenges. It is often unclear what qualifies as “relevant”, particularly when documentation is spread across corporate groups, cloud providers or third-party suppliers. Since claimants may challenge not only the adequacy but also the accessibility and clarity of the disclosure, defendants are under pressure to provide documentation that is both comprehensive and comprehensible.

This mechanism is likely to be a powerful weapon for claimants, especially in complex case such as those involving AI systems where proving causation or defectiveness is often challenging. Once a claimant meets the plausibility threshold and secures a disclosure order, any shortcomings in disclosure can shift the evidentiary balance in their favour. This will also drive-up compliance costs, as firms must devote substantial resources to recording, storing and presenting information in ways that will meet the higher legal standards set by PLD, including in litigation up to 25 years later.

This concern is further amplified, in particular because German courts are largely unfamiliar with many of the concepts employed in the Ministerial Draft, and because the introduction of evidence disclosure constitutes a new feature in German product liability law. For example: while the Ministerial Draft limits disclosure to what is deemed “necessary and proportionate,” it nonetheless fails to provide clear definitions or robust procedural safeguards.

[1] Fully automated driving functions refer to the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) Level 2-4 autonomous vehicle (AV). Civil liability for negligence continues to apply to drivers or operators, as well as to AV system providers. They may also be subject to criminal liability for negligence, with the driver’s obligations varying depending on the level of automation. These obligations may include monitoring the system or intervening if it malfunctions.

[2] Galasso, A., & Luo, H. (2024). Product Liability Litigation and Innovation: Evidence from Medical Devices (No. w32215). National Bureau of Economic Research.

3. Product Liability and Mass Litigation in Germany

Safety issues related to product safety, including safety-related cybersecurity requirements, under the proposed product liability law may lead to civil liability and trigger collective actions. The EU PLD states that claims for damages may be brought by persons to whom a claim has been transferred, or by those acting on behalf of one or more injured parties under EU law, national law or contract. The Ministerial Draft expressly provides only that claims for damages may be brought by natural persons. All other possibilities foreseen by the EU PLD, as clarified in the explanatory memorandum to the Ministerial Draft, already follow from the applicable provisions of German law and therefore do not require separate transposition. However, the interplay between the various actors entitled to bring claims in Germany is central to understanding the regulation’s potential economic impact. By extending liability into the digital domain, it increases the risk of mass litigation for digital firms and for those supplying products to non-digital industries.

The German system of collective actions can be divided into two strands. The first strand covers cases brought under specific laws: the Model Proceedings in Capital Market Disputes Act (KapMuG); the Declaratory Action (Musterfeststellungsklage), and the Redress Action (Abhilfeklage), both now governed by Germany’s Consumer Rights Enforcement Act (VDuG), which transposes the EU’s Representative Actions Directive in Germany; and actions for injunctive relief under the German Injunctions Act (UKlaG) and the Unfair Competition Act (UWG).

The second strand is the assignment model (Abtretungsmodell), under which individual claims are transferred to a third party that pursues them in court on behalf of the claimants. This model is not explicitly regulated by a single law but derives from general provisions of German civil and procedural law.[1] [2]

Key differences distinguish the assignment model from the German Consumer Rights Enforcement Act. Under the assignment model, consumers transfer their claims to a third party that becomes the legal claimant, whereas under the Consumer Rights Enforcement Act only qualified consumer organisations (QEs), including QEs from other EU member states, can bring representative actions. Litigation funding is another distinction: under the German Consumer Rights Enforcement Act it is capped at 10 percent of compensation, while no such limit applies in the assignment model.[3] In addition, under the German Consumer Rights Enforcement Act, QEs must disclose the sources of their funding and, if third-party funded, provide the full unredacted contract to allow scrutiny for conflicts of interest. This also applies in cases where the financing of the action occurs only after the action has been filed.

The absence of these restrictions in the assignment model has made it increasingly popular and fostered an ecosystem of litigation funders, lawyers and other actors whose business models centre on mass claims. For funders, litigation offers significant returns[4]: more than 40 private funders now operate in Germany, the second-highest number in the EU after the Netherlands.[5] For lawyers, the assignment model opens the door to cases that would otherwise be difficult under German law, which restricts contingency fees, since funders cover legal fees and finance the collection of claims.

Claim-collection firms form another pillar of this ecosystem. The 2021 German Legal Tech Law allows collection agents offering debt recovery services to pursue single claims in exchange for a success fee or a share of compensation. These agents operate online platforms that typically charge 20 to 40 percent of the compensation awarded, a high rate reflecting limited competition.[6] Such platforms have been used to gather claims in the Dieselgate and Truck Cartel cases, as well as disputes over flight cancellations, tenants’ rights and rent control.[7]

Finally, Germany’s mass-litigation ecosystem is reinforced by a growing litigious culture, in part facilitated by the availability of legal protection insurance. This insurance, well-established and trusted by consumer covers legal costs, lawyers’ fees, court expenses and other charges, lowering the barriers to litigation. While this strengthens consumers’ ability to assert their rights, it also contributes to a higher overall volume of claims.

[1] For example, the German assignment model is supported by Section 398 the German Civil Code (Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch) (assignment) and Section 59 of the German Code of Civil Procedure ZPO (Joinder of parties in communities of interest with regard to the disputed right, or where the cause is identical). Available at: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_zpo/englisch_zpo.html#p0231

[2] In Germany, owing to the presence of a highly active litigation-acquisition industry among law firms, a large number of individual consumer actions concerning the same subject matter remain common. This is particularly evident in cases involving alleged small-scale damages, as illustrated by the thousands of ongoing data protection claims.

[3] Becker, M., de Lind van Wijngaarden. & Mallmann, R. (2023, September 29). Redress Action in Germany – the new kid on the block? Freshfields. Available at: https://riskandcompliance.freshfields.com/post/102iowe/redress-action-ingermany-the-new-kid-on-the-block

[4] For example, in the case of Bates v. the UK Post Office, funders’ profits were equal to 41 percent and defended this return as being within the legal cap for comparable agreements. See Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025, p. 108.

[5] Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Zilli, R. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in the UK. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 6/2025, 78 p.

[6] Plog, P. (2019, May 29). German draft law on legal tech: Take the plunge! Fieldfisher. Available at https://www.fieldfisher.com/en/insights/german-draft-law-on-legal-tech-take-the-plunge

[7] See MyRight (https://www.myright.de); Financialright (https://www.financialright.de);Flightright (https://www.flightright.com); WenigerMiete.de (https://www.wenigmiete.de).

4. Lessons from Mass Litigation in Germany’s Non-Digital Sectors

The rise of collective actions in Germany has had an impact on the economy and on some of its largest firms. The Model Proceedings in Capital Market Disputes Act was introduced after Deutsche Telekom’s incorrect valuation of real estate, while the Model Declaratory Action was designed for cases such as those against Volkswagen. The latter also helped fuel the rise of collective actions through the assignment model. Beyond Germany, major companies have faced collective actions abroad. Bayer, for instance, was hit with multiple lawsuits in the United States after acquiring Monsanto.[1]

These collective actions have had real financial consequences. Their impact is visible both in the compensation paid and in the impact on the companies’ market value. A year after the Diesel scandal broke in 2015, Volkswagen’s share price had fallen by 30 percent as investors priced in reputational damage and looming compensation costs.[2] That same year, Volkswagen agreed a $14.7 billion settlement in the US[3] and paid €830 million to 260,000 car owners in Germany.[4]

The German Insurance Association (GDV) estimates that the diesel scandal generated €1.52 billion in legal costs, making it the most expensive case in the history of German legal insurance. Yet only 10.4 percent of the claims, which joined the diesel litigation were fully successful, 42.1 percent partially successful and nearly half (47.5 percent) unsuccessful.[5] All claims that were brought led to costs within the legal system. Additionally, even where only 10.4 percent of the claims brought against a company are successful, the costs in legal fees for the company, the impact on its share value and reputation remain substantial.

A further contrast can be seen in the fact that, while lawyers and litigation funders often absorb high legal costs, consumers typically receive only relatively modest amounts from such claims. The recent UK case Merricks v. Mastercard provides a good example. After a decade of costly litigation, £100 million was awarded as compensation, leaving claimants with up to £70 each if only 5 percent claimed but as little as £2.50 each if the full class of 44 million people came forward. In contrast, £46 million went to the litigation funder, with a further £54 million potentially payable as return on capital, depending on the number of claims submitted. Mr Merricks’s legal team billed more than £18.1 million. Mastercard’s legal costs were undisclosed but likely much higher.[6] Studies in other jurisdictions where mass litigation is common confirm this pattern of high rewards for lawyers and funders, but meagre returns for consumers.[7]

Moreover, although the state does not directly finance the parties’ legal fees, the operation of the court system is publicly funded. Germany’s judiciary is already under strain. According to the European Commission’s 2023 Rule of Law Report, resources for the justice system remain inadequate, with 78 percent of judges and 92 percent of prosecutors reporting insufficient staffing.[8] In this context, a further rise in collective actions and PLD-based claims could exacerbate existing capacity constraints, placing additional pressure on courts and, ultimately, increasing costs for taxpayers.

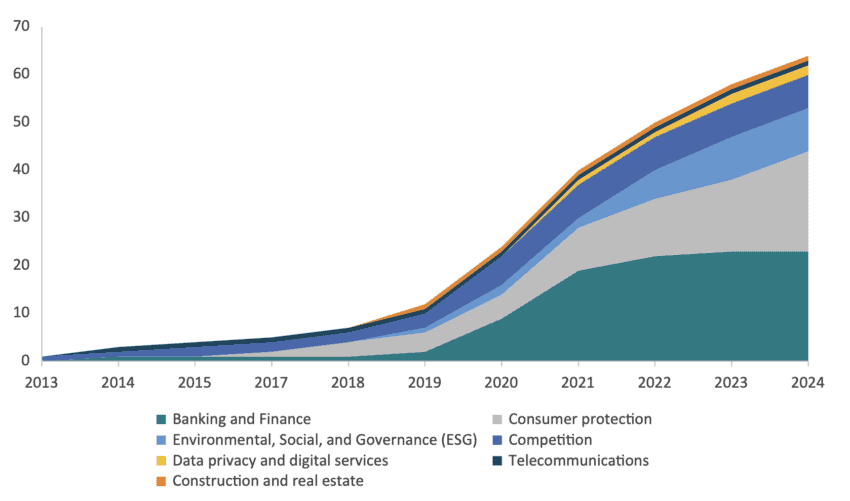

Collective actions via the assignment model have affected a wide range of industries in Germany. Figure 1 shows the cumulative number of collective actions across major economic sectors between 2013 and 2024, including “Competition” cases such as the Trucks Cartel. Other prominent examples include challenges in the banking sector (e.g. unlawful interest rate adjustments), disputes over energy prices, and claims linked to digital services. The figure illustrates that as the overall number of cases rises, the range of sectors affected has also expanded.

Figure 1: Cumulative number of collective action lawsuits across economic areas, Germany (2008–2024) Source: Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025, p. 108.[9]

Source: Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025, p. 108.[9]

[1] Bayer. (2020, June 24). Bayer announces agreements to resolve major legacy Monsanto litigation. Bayer. Available at: https://www.bayer.com/media/en-us/bayer-announces-agreements-to-resolve-major-legacy-monsanto-litigation/

[2] Independent UK. (2016, September 17). Volkswagen diesel emissions scandal: the toxic legacy. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/leading_business_story/volkswagen-diesel-emissions-scandal-the-toxic-legacy-a7312056.html

[3] Office of Public Affairs, US Department of Justice. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/volkswagen-spend-147-billion-settle-allegations-cheating-emissions-tests-and-deceiving

[4] Volkswagen. (2020, February 28). VW to pay €830m settlement to German consumers. Available at: https://www.dw.com/en/dieselgate-volkswagen-to-pay-830-million-settlement-to-german-consumers/a-52572281

[5] “Fully successful” means that claimants received the full compensation, while “partially successful” means that claimants received less than what they demanded. Source: GDV. Abschlusszahlen zum Diesel-Skandal: Streitwert bei 10,8 Milliarden Euro. Available at: https://www.gdv.de/gdv/medien/medieninformationen/abschlusszahlen-zum-diesel-skandal-streitwert-bei-10-8-milliarden-euro-162788

[6] FCJ. (2025, February 25). Merricks-Mastercard Settlement Shows Real Winners from Class Actions. Available at: https:// fairciviljustice.org/news/the-merricks-mastercard-settlement-shows-the-real-winners-from-class-actions/

[7] In an Australian study, Professor Vince Morabito found that litigation funders received a substantial share of class action settlements. In federally funded class actions, funders took 27% of all settlement proceeds, about $528 million out of $1.96 billion, as fees. Across all funded class actions, the share was similar at 27%, with $583 million out of $2.17 billion allocated to funder fees. See: Morabito, V. (2019). An Evidence-Based Approach to Class Action Reform in Australia: Common Fund Orders, Funding Fees and Reimbursement Payments. Funding Fees and Reimbursement Payments (January 31, 2019).

[8] European Commission (2023). 2023 Rule of Law Report Country Chapter on the rule of law situation in Germany. SWD (2023) 805 final.

[9] The Consumer Protection category also encompasses cases falling under product liability.

5. What’s at Stake? Undermining the Growth of Germany’s ICT Sector

5.1 The New Product Liability Act’s Impact on ICT

How Germany implements the draft Product Liability Act could have significant economic consequences for Germany’s ICT sector. The most immediate risk is a surge in mass litigation claims whenever regulatory or safety issues occur, potentially even if the product is not at fault.

As described in Chapter 2, firstly, the Ministerial Draft expands the definition of a “product” to cover software, digital files and related services such as operating systems, apps and AI systems. This broadens the range of claims that can be brought against ICT firms. Secondly, it introduces a rebuttable presumption of defectiveness, lowering the bar for collective actions. Thirdly, it extends liability beyond the final manufacturer to include component suppliers and service providers. This widens the pool of companies exposed to claims, including German SMEs supplying software, digital files or related services that represented 42 percent of the sector’s total value added.[1] Fourthly, it extends liability to defects that appear after a product is released, creating open-ended exposure for digital products. Because many of these products are constantly updated, any design change, even one that improves safety, could be construed in court as an admission that the earlier version was flawed. Finally, ICT has certain inherent features that make it especially vulnerable to collective actions in case of a safety or other regulatory issue. For example, if one app suffers a data breach, many users are likely to be affected at the same time and in the same way.

Beyond the risk of mass litigation, the new German Product Liability Act also adds legal uncertainty. This stems partly from the vague definition of defectiveness and the difficulty of assigning liability in digital and AI systems, as explained earlier, and from conflicts and overlaps with existing digital and data laws.

In addition to the case of Road Traffic Act (StVG) mentioned in Chapter 2, Cybersecurity law provides a clear illustration of these overlaps. In Germany, the BSIG (Act on the Federal Office for Information Security) and the IT Security Act 2.0 (IT-SiG 2.0) form the core cybersecurity framework. Once the new Product Liability Act is adopted, a single incident could expose companies both to regulatory sanctions under BSIG/IT-SiG 2.0 and to liability claims under the new rules. This overlap also raises the question of enforcement. Currently, the BSI (Germany’s national cybersecurity authority) holds regulatory powers, but under the Ministerial Draft courts could also be asked to judge the adequacy of cybersecurity protections. In short, digital companies could simultaneously face claims for compensation under both contract law (warranty) and tort law (product liability) as well as regulatory enforcement (BSIG/IT-SiG 2.0).

This increasing uncertainty, along with the costs of potential litigation such as legal fees, damages and reputational harm, will force digital firms to carefully document every interaction with a third party or service in order to protect themselves which will increase compliance costs.

Regulatory burden will weigh on Germany’s economic performance. As Mario Draghi noted in his report on EU competitiveness, the administrative cost of regulation could reach €150 billion a year, or 1.3 percent of the EU’s GDP.[2] Other evidence shows that restrictive regulation slows the adoption of digital technologies, a critical driver of productivity and competitiveness. A 10 percent increase in regulatory restrictions and digital readiness leads to a 1.3 percent fall in value added.[3] That may sound modest but applied to Germany’s private-sector output of €3 trillion, it means €37 billion lost every year.

Finally, the growing role of mass litigation raises a deeper concern: the outsourcing of regulatory enforcement to private lawsuits. Traditionally, compliance with regulatory duties, whether in cars, cybersecurity or other sectors, has been overseen by public authorities with technical expertise and a public mandate. Under the draft product liability framework, however, civil courts prompted by private claims would be asked to judge whether a company’s measures, for instance in cybersecurity, were adequate. In complex cases, courts would almost certainly need to appoint costly independent technical experts. Consumers may also have to commission private expert opinions to back up their claims, adding further costs. As the Merricks v. Mastercard case shows, this raises doubts over whether mass litigation is a suitable or cost-effective mechanism: whether it truly helps consumers, or simply fuels litigation markets while placing additional strain on the courts. This concern is further compounded by the intended abolition of the previous deductible for property damage and the overall liability cap. A legislative determination – supported by robust economic evidence – that the previous thresholds or caps were excessive is notably absent.

5.2 ICT as a Central Pillar of the German Economy

As already shown, the potential negative effects of the Ministerial Draft on the German digital sector can be significant. The ICT sector is not only a major part of the German economy but also one of its main engines of growth. This role is especially critical given Germany’s recent economic underperformance: between 2022 and 2024, it recorded the fourth-slowest average GDP growth in the EU.[4]

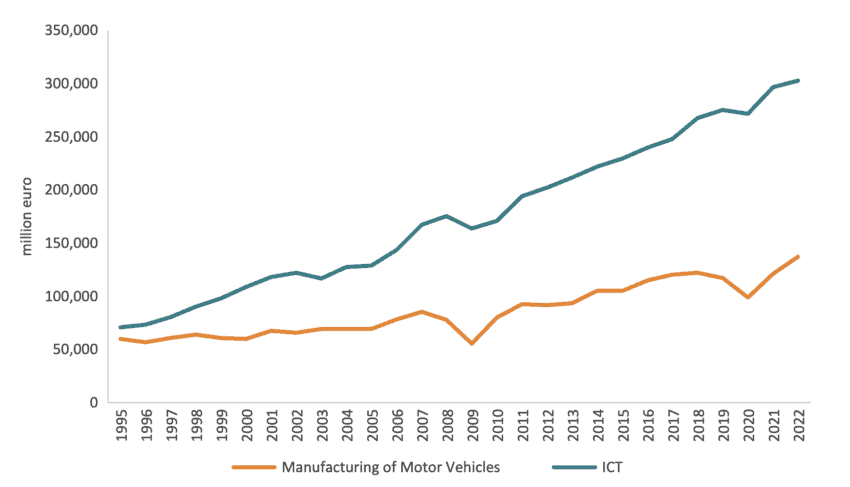

Figure 2 shows the size of the German ICT industry, measured by gross value added, alongside the automotive sector – long regarded as a cornerstone of Germany’s economy. The goal of this analysis is not to contrast ICT with cars or manufacturing, but to use them as benchmarks to highlight ICT’s economic weight. The data shows that, in the mid-1990s, the ICT and automotive sectors made similar contributions to the German economy. Since then, ICT has surged ahead, rising from 4 to 12 percent of the economy, while the automotive sector grew only from 3 to 5 percent.

Figure 2: Gross value added in the German automotive and ICT industries (1995–2022) Note: Authors’ calculation based on Eurostat national accounts. Units: Chain linked volumes (2005), million euro. Note: Eurostat national accounts did not include the aggregate ICT sector. The ICT sector was approximated using the following NACE sectors: Manufacture of Computer, Electronic and Optical Products (C26); Information and Communication (J); and Repair of Computers and Personal and Household Goods (S95).

Note: Authors’ calculation based on Eurostat national accounts. Units: Chain linked volumes (2005), million euro. Note: Eurostat national accounts did not include the aggregate ICT sector. The ICT sector was approximated using the following NACE sectors: Manufacture of Computer, Electronic and Optical Products (C26); Information and Communication (J); and Repair of Computers and Personal and Household Goods (S95).

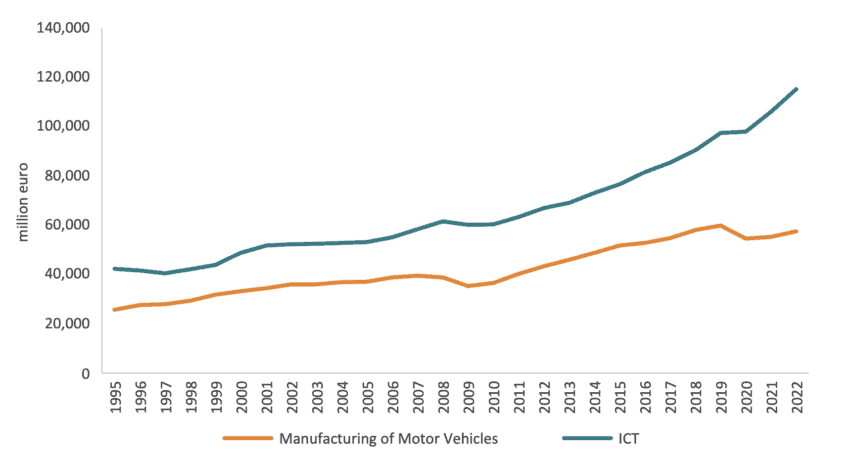

A similar pattern appears in Figure 3 for wages. In 2023, the ICT sector employed 1.6 times more people than the car industry, and total wages paid by ICT firms, therefore, exceeded those in the automotive sector. More important than the levels, however, is the trend. Since 2010, the gap has widened: ICT’s share of total wages rose from 5 to 7 percent, while automotive stayed flat at 3 percent.

Figure 3: Total wages and salaries paid in the German automotive and ICT industries (1995–2022) Note: Authors’ calculation based on Eurostat national accounts. Units: Current prices, million euro. Note: Eurostat national accounts did not include the aggregate ICT sector. The ICT sector was approximated using the following NACE sectors: Manufacture of Computer, Electronic and Optical Products (C26); Information and Communication (J); and Repair of Computers and Personal and Household Goods (S95).

Note: Authors’ calculation based on Eurostat national accounts. Units: Current prices, million euro. Note: Eurostat national accounts did not include the aggregate ICT sector. The ICT sector was approximated using the following NACE sectors: Manufacture of Computer, Electronic and Optical Products (C26); Information and Communication (J); and Repair of Computers and Personal and Household Goods (S95).

Figures 2 and 3 point to two clear conclusions. First, ICT has outperformed the automotive sector by a wide margin. Second, ICT has become a central pillar of the German economy, underpinning both value added and wages.

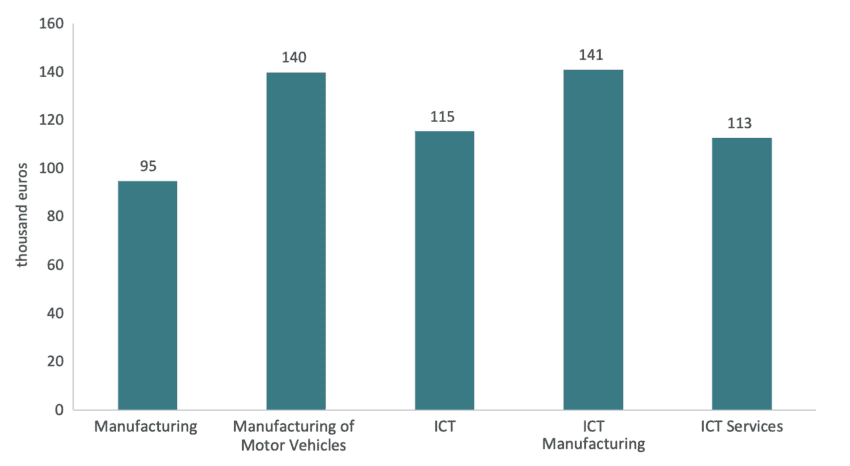

Moreover, the ICT sector is not only larger and faster-growing than often assumed; it is also highly competitive, as shown by labour productivity. Figure 4 compares labour productivity in manufacturing, automotive and ICT, broken down into ICT manufacturing and ICT services. The results are striking: ICT overall outperforms German manufacturing. While automotive still shows higher productivity than ICT as a whole, productivity in the ICT manufacturing sector surpasses automotive, and ICT services are more productive than German manufacturing overall.

Figure 4: Labour productivity by sector in Germany (2023) – Manufacturing, automotive, ICT, ICT manufacturing, and ICT services Note: Authors’ calculation based on Eurostat Structural Business Indicators. Units: thousand euros.

Note: Authors’ calculation based on Eurostat Structural Business Indicators. Units: thousand euros.

5.3 ICT and the Competitiveness of German Manufacturing

The impact of the implementation of the Ministerial Draft will reach well beyond the ICT sector. Advances in Germany’s digital industries are central to modernising its manufacturing base. Digital technologies such as AI and Machine Learning, quantum computing, the Internet of Things, big data, health IT, cloud services, data centres, virtual and augmented reality, 5G, edge computing, or digital factory solutions are now vital for competitiveness. This is particularly important in Germany, where manufacturing accounts for 27 percent of value added, four points above the EU average.

The importance of digital technologies is especially clear in the automotive sector, now increasingly reliant on AI and digital integration. Driver-assistance and autonomous systems depend on dozens of cameras, sensors and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) devices, all managed by complex software. To stay at the technological frontier, German carmakers will need to source many of these technologies from external suppliers.

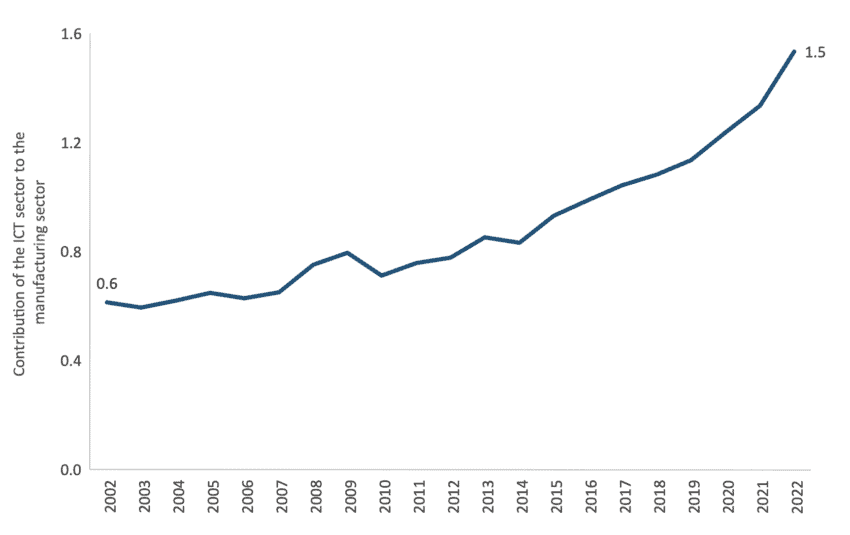

This trend is not new. For years, the ICT sector has steadily increased its contribution to manufacturing.[5] As Figure 5 shows, the amount of ICT sector input required in the production of one unit of the manufacturing sector has more than doubled as the German economy continues to digitalise.

Figure 5: Contribution of the ICT sector to German manufacturing Note: Authors’ calculation based on OECD Input-Output Tables. Note: OECD Input-Output Tables did not include the aggregate ICT sector. The ICT sector was approximated using the following NACE sector: Information and Communication (J).

Note: Authors’ calculation based on OECD Input-Output Tables. Note: OECD Input-Output Tables did not include the aggregate ICT sector. The ICT sector was approximated using the following NACE sector: Information and Communication (J).

As already indicated, digital technologies are becoming more embedded in manufacturing. The resulting pressures on ICT (e.g., greater legal exposure, heavier regulatory burdens and weaker innovation) arising from the extension of liability to software developers, hardware makers and digital service providers will spill over into the wider economy, particularly manufacturing. German industry will continue to adopt digital technologies, but the intended new law risks making the process slower and more costly.

[1] Eurostat. Structural business statistics. Data for 2023. ICT sector included the following industrial categories: (C261) Manufacture of electronic components and boards; (C262) Manufacture of computers and peripheral equipment; (C263) Manufacture of communication equipment; (C264) Manufacture of consumer electronics; (C268) Manufacture of magnetic and optical media; (G465) Wholesale of information and communication equipment; (J582) Software publishing; (J611) Wired telecommunications activities; (J612) Wireless telecommunications activities; (J613) Satellite telecommunications activities; (J619) Other telecommunications activities; (J620) Computer programming, consultancy and related activities; (J631) Data processing, hosting and related activities; web portals; (S951) Repair of computers and communication equipment; (S952) Repair of personal and household goods;

[2] Draghi, M. (2024). The future of European competitiveness: In-depth analysis and recommendations. European Commission, p. 317.

[3] Guinea, O., Sharma, V., van der Marel, E., & du Roy, O. (2025). Breaking Barriers, Boosting Growth: Unlocking the Power of Digital Technology for Europe’s Competitiveness. ECIPE, Brussels, Policy Brief 14/2025, p. 27.

[4] Eurostat. Real GDP growth rate – volume.

[5] Figure 5 measures the total direct and indirect input requirements from the ICT industry to produce one unit of final demand from the manufacturing industry.

6. Quantifying the Costs of the Intended New Product Liability Law

6.1 Cost Estimates in the German Government’s Explanatory Memorandum

The Ministerial Draft to modernise product liability introduces several types of costs. Official estimates are surprisingly low, reaching a total for the country of around €72,000; they relate mainly to additional costs in legal proceedings and the administrative implementation of the regulation. Most of these costs will fall on the public sector, as state and federal courts will need to allocate extra resources for evidence disclosure and the publication of decisions.

These estimates, however, overlook the costs of capacity building within the judiciary. The Ministerial Draft introduces novel disclosure obligations to the procedural rules, brand-new obligations that did not previously exist in German product liability law. German judges and court staff have little experience with such mechanisms, routine in common law systems but novel in Germany. Effective implementation will require specialised training for judges, clerks and court staff on handling disclosure requests, assessing proportionality, and balancing them against confidentiality and trade secrets. Training on this scale, covering hundreds of judges across multiple court levels, entails significant costs for curriculum design, delivery and ongoing education.

By contrast, for companies the explanatory memorandum claims there will be “no change in compliance costs for the economy.” The only additional expense foreseen is the time required to respond to court orders for evidence disclosure. It assumes firms will spend about 40 hours processing requests in 1,000 cases a year, at a total cost for the firms of €26,000.

The explanatory memorandum also acknowledges other potential costs, including those highlighted earlier in this study: a wider range of liable parties, broader categories of damages (now including data), higher litigation risks for innovative products, and easier claim assertion through legal presumptions. However, these costs were not quantified. As a result, the total estimated costs in the Ministerial Draft’s explanatory memorandum amounted to €26,000 and refer to some administrative costs.

6.2 Economic Costs of Mass Litigation

6.2.1 Methodology

An important economic cost that will be triggered by the Ministerial Draft will come in the form of a rise in the number of representative- and collective actions. To quantify these costs, this paper applies an updated version of the methodology developed in Erixon et al. (2025), which assessed the economic impact of mass litigation across the EU.[1] The approach builds on US research that estimates the cost of mass litigation to the US economy and adapts it to the European context, providing a basis for inferring the potential impact of rising collective actions in EU countries.

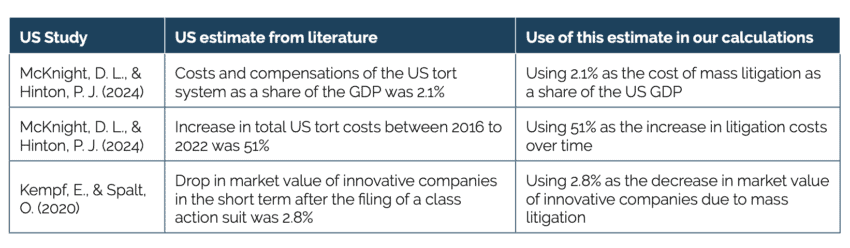

The methodology begins with a set of variables identified through a review of the existing literature. To be included, the variables had to meet two criteria: they needed to have close equivalents in Germany to those used in US studies, and reliable statistical data had to be available. The final selection covered three variables: the cost of private enforcement as a share of GDP, litigation costs, and market capitalisation. The next table sets out these variables alongside the empirical studies from which they are drawn, the definitions used, and the way in which they feed into the estimation of mass litigation’s impact in Germany.

Table 1: Key variables impacted by mass litigation The estimates from the US empirical literature form the basis for assessing the potential economic impact of an increase in collective actions in Germany. That said, it is hard to judge how closely Germany’s system of mass litigation resembles its US counterpart. To account for this uncertainty, a scenario-based analysis is used to capture the range of possible outcomes. These scenarios reflect that while collective actions have grown in use the public regulatory enforcement model is still dominant in Germany.

The estimates from the US empirical literature form the basis for assessing the potential economic impact of an increase in collective actions in Germany. That said, it is hard to judge how closely Germany’s system of mass litigation resembles its US counterpart. To account for this uncertainty, a scenario-based analysis is used to capture the range of possible outcomes. These scenarios reflect that while collective actions have grown in use the public regulatory enforcement model is still dominant in Germany.

The study sets out three scenarios (Low, Medium and High Growth). The scenarios assume that if collective actions in Germany continue to rise, the economic impact would be proportional to the effects identified in the US studies. Each scenario estimates the costs for the three variables identified earlier – private enforcement as a share of GDP, litigation costs and market capitalisation. These are independent exercises, and the results are not designed to be added together.

Following the methodology in Erixon et al. (2025), the scenarios are defined as follows:

- Low Growth Scenario: assumes that the economic impact of mass litigation growth in Germany will be equivalent to 10 percent of the economic effects observed in empirical studies in the US.

- Medium Growth Scenario: assumes that the economic impact of mass litigation growth in Germany will be equivalent to 20 percent of the economic effects observed in empirical studies in the US.

- High Growth Scenario: assumes that the economic impact of mass litigation growth in Germany will be equivalent to 30 percent of the economic effects observed in empirical studies in the US.

Annex 1 provides full details of the methodology and calculations behind each scenario and variable.

The approval of the Ministerial Draft, which extends liability to software and other digital products, is unlikely on its own to lift the number of collective actions to the levels modelled in the three scenarios. The costs presented below should, therefore, not be attributed to the new law alone. Even so, it is clear that the new law will add to the growth of collective actions in Germany. As argued in Chapter 3 and 5, with a well-developed ecosystem of lawyers and litigation funders already in place, and a rapidly expanding digital economy, the modernisation of the product liability law will result in an increase in collective actions. The growth scenarios may not be far from Germany’s current trajectory and the assumptions of 10, 20 and 30 percent of US costs are, if anything, conservative.[2]

In addition, the costs of growing collective actions in Germany will come on top of those already imposed by the country’s burdensome safety laws and consumer protection regulations. Therefore, for German businesses, the costs of private enforcement associated to collective actions will be added to the existing burden of public regulatory enforcement, which is already substantial.

6.2.2 Private Enforcement Costs

Private enforcement is used when individuals or groups of individuals bring a court case to claim compensation for harm or for other redress due to a regulatory breach or other legal cause of action. Collective actions are the most prominent example, especially when breaches affect large numbers of consumers in the same way. The costs of private enforcement for companies include the paying out of compensation that may be awarded by a court or settlement payments in case the case is settled out of court, as well as higher insurance premiums for protection against litigation risks.

In 2022, the costs and compensation payouts of the US tort system as a share of GDP was 2.1 percent. Table 2 estimates the cost of private enforcement as a share of Germany’s GDP.[3] 10, 20 and 30 percent of 2.1 is equal to 0.21, 0.42, and 0.63 percent. Germany had a GDP amounting to €4.33 trillion in 2024. The estimates for the three scenarios are presented below.

Table 2: Cost of private enforcement as a share of GDP – scenario-based analysis Source: Author’s calculations based on Eurostat data on GDP, 2024.

Source: Author’s calculations based on Eurostat data on GDP, 2024.

To put these figures into perspective, the recent German budget for 2025, allocated €22 billion to the development of rail infrastructure in the country.[4] Therefore, the cost of private enforcement in the high-growth scenario for Germany could be higher than Germany’s rail infrastructure budget in 2025.

6.2.3 Litigation Costs

Mass litigation is an expensive method for consumer redress because litigation costs comprise a large and often disproportionate share of the financial outcomes of collective actions, limiting the final compensation received by individuals.

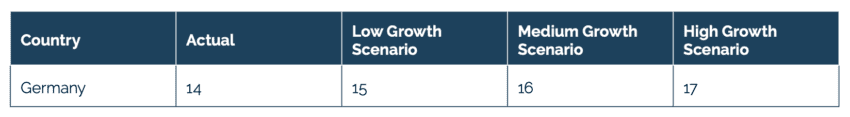

Between 2016 and 2022, tort costs in the US increased by 51 percent.[5] According to the World Bank’s Doing Business in Europe (2020) report[6] litigation costs Germany amounted to 14.1 percent of a claim’s value in 2020.[7] This statistic measures the average of attorney costs, court costs, and enforcement costs as a share of claim value.

Using the scenario analysis methodology, we apply the 51 percent increase in US tort costs over time to the three scenarios. The resulting estimates are 5.1, 10.2 and 15.3 percent (representing 10, 20, and 30 percent of the 51 percent figure respectively). Applying the projected growth rates of 5.1, 10.2, and 15.3 percent to the litigation costs in Germany, we find the following litigation costs as a share of the claim value presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Increase in litigation costs (percentage) – scenario-based analysis Source: Author’s calculations based on World Bank, Doing Business in Europe (2020).

Source: Author’s calculations based on World Bank, Doing Business in Europe (2020).

6.2.4 Innovation Costs

Innovative products, by their nature, involve greater uncertainty about risks and side effects. This makes them more exposed to collective actions. When litigation risk falls most heavily on new products, companies may cut back investment in technology and redirect resources to other less innovative activities and to legal compliance.[8] As a result, the balance of R&D could move away from breakthrough innovations towards safer, less litigation-prone products.

Furthermore, mass litigation can have an immediate and lasting impact on the market value of innovative firms. Research by Kempf and Spalt (2020),[9] which examined the effect of private enforcement on companies’ market capitalisation, found that collective actions cut the value of innovative firms by 2.8 percent. Such lawsuits often target successful innovators disproportionately, reducing their capacity and incentive to invest in new products.

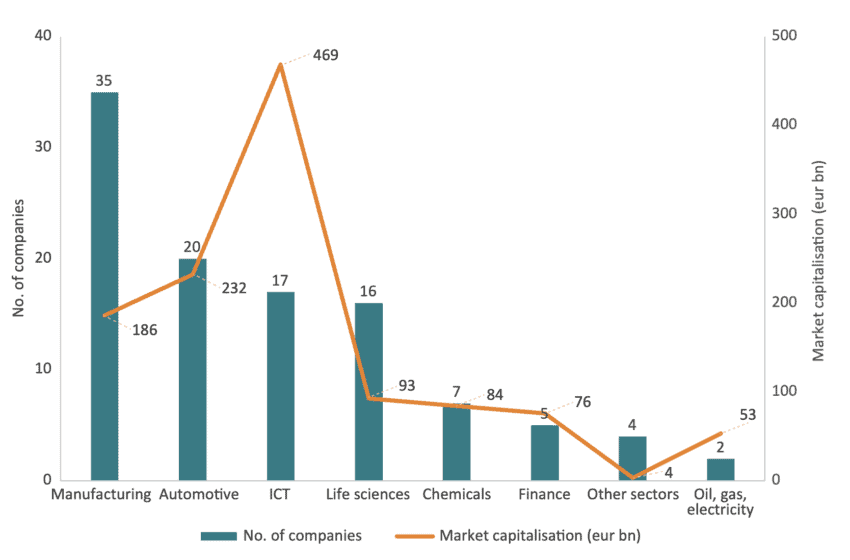

We classify the top 106 German R&D investors by economic sector. Data on market capitalisation comes from the EU Joint Research Centre’s annual report, which tracks the top 2,500 global R&D investors – widely regarded as the world’s most innovative firms.[10] Figure 6 shows the distribution of the 106 most innovative German companies by sector, together with their combined market capitalisation. Annex 2 provides a full list of the companies and their sectors. The importance of the ICT sector, highlighted in Chapter 5, is also clear here. Of the 106 most innovative German firms, 17 are in ICT, representing 39 percent of total market capitalisation.

Figure 6: Market capitalisation of the top 106 German R&D investors by sector Source: Author’s calculations based on European Commission (2023). The “Other sectors” column include four companies in food production, travel and leisure, support services, and industrial metals and mining.

Source: Author’s calculations based on European Commission (2023). The “Other sectors” column include four companies in food production, travel and leisure, support services, and industrial metals and mining.

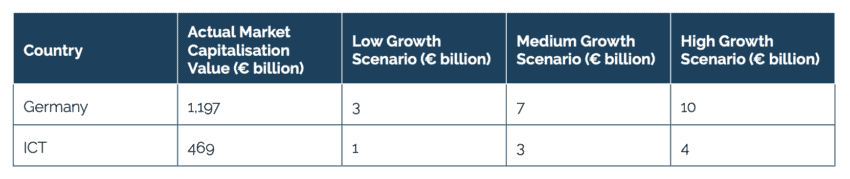

Using the scenario methodology, we applied 10, 20, and 30 percent of Kempf and Spalt’s 2.8 percent estimate to the aggregate market capitalisation of the 106 most innovative companies in Germany. This produced estimates for the Low (10 percent), Medium (20 percent), and High (30 percent) Growth Scenarios. The results are shown in Table 4.

In total, the projected decline in market capitalisation for the top 106 German R&D investors ranges from €3.35 billion to €10 billion. To put this in perspective, gross domestic expenditure on R&D by the German public sector in 2023 was €15 billion. A high growth scenario of mass litigation in Germany would lead to a fall in the market capitalisation of Germany’s most innovative companies worth two-thirds of Germany’s total government sector expenditure on R&D in 2023.

Applying the same scenario methodology to the 17 German companies in the ICT sectors yields similarly striking results. As explained previously, the implementation of the Ministerial Draft could result in increased exposure to collective actions in the ICT industry. Our calculations show that for these 17 R&D-intensive firms the projected decline in market capitalisation ranges from €1 billion to €4 billion.

Table 4: Reduction in market capitalisation for the top 106 and 17 ICT German R&D investors – scenario-based analysis Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on European Commission (2024). The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard.

Source: ECIPE’s calculations based on European Commission (2024). The 2024 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard.

Finally, the effects of a decline in market capitalisation will also be felt by households, particularly savers and both current and future pensioners. In 2024, German households invested 27 percent of their savings in pensions and insurance schemes. Moreover, 60.4 percent of pension fund assets in Germany were allocated to capital market investments.[11] Although there is no public data on how much of these savings are invested in domestic companies, it is likely that a substantial share is held in national firms. This suggests that any fall in market capitalisation triggered by mass litigation under the new EU PLD law and its national transposition act could also adversely affect household wealth and future pension returns in Germany.

[1] Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025, 108 p.

[2] The 10-30 percent range used in the scenarios also reflects structural differences between the US and German litigation systems. The US model is significantly more aggressive due to factors such as pre-trial discovery procedures, the use of juries, punitive damages, and higher contingency fees. These features tend to inflate both the volume and value of claims. By contrast, Germany’s collective redress system is more restrained, with stricter procedural rules, making the assumed share of US costs a conservative estimate.

[3] McKnight, D. L., & Hinton, P. J. (2024), Tort Costs in America: Third Edition. US Chambers of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform. The study defines tort costs as the aggregate amount of judgments, settlements, and legal and administrative costs to adjudicate private claims and enforcement actions. The costs of the tort system also include the portion of liability insurance premiums used to pay administrative expenses and overheads and contribute to the profits of insurers.

[4] Federal Ministry of Finance (2025). Fiscal foundations for the coming years: German government adopts 2025 federal budget, benchmark figures to 2029 and implementation of the €500bn investment package. Accessed at: https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2025/2025-06-24-2-government-draft-2025-federal-budget.html

[5] McKnight, D. L., & Hinton, P. J. (2024), Tort Costs in America: Third Edition. US Chambers of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform.

[6] World Bank (2020), Doing Business in Europe. Accessed at: https://archive.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/media/Profiles/Regional/DB2020/EU.pdf. It measures the average of attorney costs, court costs and enforcement costs as a share of claim value. The indicator focuses specifically on commercial litigation, including class actions and non-class actions.

[7] The chosen variable includes a note of caution. The estimates for litigation costs from the McKnight & Hinton 2024 study, not only include the costs of the tort system but also the compensation amounts. Meanwhile, the German estimates for this indicator only include the litigation costs and not the compensation values. Nonetheless, the estimates for the US are the most recent and the most similar estimates we were able to find through our literature review for the scenario-based analysis. Moreover, since the scenario-based analysis is only estimating an approximate impact of the increase in private litigation in Germany, the estimates for the US provide us with a viable answer.

[8] The threat of lawsuits influences the business decisions of 62 percent of companies, leading them to prioritise litigation avoidance over strategic considerations like business growth. See McKnight, D. L., & Hinton, P. J. (2011). Creating conditions for economic growth: the role of the legal environment. NERA Economic Consulting.

[9] Kempf, E., & Spalt, O. (2020). Attracting the sharks: Corporate innovation and securities class action lawsuits. Management Science, 69(3), 1805-1834.

[10] Nindl, E., Confraria, H., Rentocchini, F., Napolitano, L., Georgakaki, A., Ince, E., Fako, P., Tuebke, A., Gavigan, J., Hernandez Guevara, H., Pinero Mira, P., Rueda Cantuche, J., Banacloche Sanchez, S., De Prato, G. and Calza, E., The 2023 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2023, doi:10.2760/506189, JRC135576

[11] OECD. (2023). Share of households and NPISHs’ currency and deposits, debt securities, equity, investment fund shares, life insurance and annuity entitlements and pension entitlements as a percentage of their total financial assets.

7. Conclusion

The Ministerial Draft largely reproduces the EU PLD, offering little additional guidance or adaptation to the German legal system. As a result, several legal and procedural notions remain ambiguous, which could lead to conflicting interpretations and uncertain legal outcomes. Such uncertainty carries considerable economic risks, particularly for the digital and technology sectors. While the intended law aims to bring digital products into alignment with physical goods in terms of liability, it overlooks the unique characteristics of digital technologies, such as continuous updates and user-driven adaptations. This misalignment increases the regulatory burden on businesses and introduces new legal uncertainty, which could stifle innovation and economic growth.

Key findings include:

- Increased Regulatory Burdens: The expanded scope of the liability framework to include software, digital files, and services increases compliance costs, especially for SMEs in the ICT sector. The new intended product liability law will require considerable resources to be allocated to ensure the production of comprehensive documentation and carrying out of additional testing which may discourage innovation and raise operational costs.

- Mass Litigation Risks: By lowering the thresholds to bring litigation and introducing pro-claimant presumptions that effectively reverse the burden of proof in certain situations, the new intended product liability law increases the likelihood of mass litigation. In addition, the new law increases the number of companies that may be targeted by including in its scope digital supply chains and components. This will contribute to a surge in collective actions, the costs of which, as well as the reputational harm, will be negative for German businesses, particularly in the digital sector.

- Impact on Innovation: The threat of litigation could lead firms to prioritise risk aversion over innovation, shifting their focus from breakthrough technologies to safer, less complex products. This could slow the pace of technological advancements, particularly in those high and emerging tech areas that are critical if Germany’s and the EU’s growth and competitiveness strategies are to succeed.

- Broader Economic Implications: The economic costs associated with the implementation of the Ministerial Draft extend beyond the digital sector, affecting the entire German economy. A slowdown in the adoption of digital technologies will have a negative impact on productivity, particularly within Germany’s industrial base, which heavily relies on digital integration for its success. Therefore, the draft law risks undermining efforts to modernise manufacturing and support the digital transition.

- An Additional Regulatory Layer: The rise of mass litigation in Germany creates a costly hybrid enforcement system for businesses. While the existing public enforcement framework already imposes substantial ex-ante compliance costs, the addition of private enforcement through collective actions will significantly increase the overall financial burden on German companies.

- An Unbalanced Law: The intended new German Product Liability Act creates disproportionate risks for suppliers of digital and other products. Lower thresholds for bringing claims, a de facto reversal of the burden of proof, and expansive disclosure obligations are especially problematic for the digital and ICT sectors. These risks are compounded by the extended 25-year limitation period for latent damages, which increases exposure, data-retention burdens and long-tail litigation risks. Germany should transpose the EU PLD with due consideration for the German legal context, provide clarity on new concepts and ensure that the risks that were discussed at the EU level when the EU PLD was negotiated (such as the misperceived reversal of the burden of proof) are not misunderstood in the transposition phase and in the subsequent application by the German courts.

References

Bayer. (2020, June 24). Bayer announces agreements to resolve major legacy Monsanto litigation. Bayer. Available at: https://www.bayer.com/media/en-us/bayer-announces-agreements-to-resolve-major-legacy-monsanto-litigation/

Becker, M., de Lind van Wijngaarden. & Mallmann, R. (2023, September 29). Redress Action in Germany – the new kid on the block? Freshfields. Available at: https://riskandcompliance.freshfields.com/post/102iowe/redress-action-ingermany-the-new-kid-on-the-block

Die Bundesregierung. (2025, July 30). Tailwind for state modernization and bureaucracy reduction. Available at: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/aktuelles/ausschuss-staatsmodernisierung-2373828

Draghi, M. (2024). The future of European competitiveness: In-depth analysis and recommendations. European Commission, p. 317.

Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Sisto, E., du Roy, O., Zilli, R., & Lamprecht, P. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in Europe. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 3/2025, p. 108.

European Commission (2023). 2023 Rule of Law Report Country Chapter on the rule of law situation in Germany. SWD (2023) 805 final.

Federal Government. Coalition Agreement. Available at: https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/federal-government/coalition-agreement-482268

Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. Regulatory Sandboxes – Testing Environments for Innovation and Regulation. Available at: https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/EN/Dossier/regulatory-sandboxes.html

Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action. (2025). Manufacturing-X – Funding Scheme for a Competitive, Resilient and Sustainable Industry. Available at: https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/EN/Publikationen/Digitale-Welt/manufacturing-x-program.pdf

Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action. (2025). Annual Economic Report. Available at: https://www.bundeswirtschaftsministerium.de/Redaktion/EN/Publikationen/Wirtschaft/annual-economic-report-2025.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4

Federal Ministry of Finance (2025). Fiscal foundations for the coming years: German government adopts 2025 federal budget, benchmark figures to 2029 and implementation of the €500bn investment package. Accessed at: https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/EN/Pressemitteilungen/2025/2025-06-24-2-government-draft-2025-federal-budget.html

Galasso, A., & Luo, H. (2024). Product Liability Litigation and Innovation: Evidence from Medical Devices (No. w32215). National Bureau of Economic Research.

GDV. Abschlusszahlen zum Diesel-Skandal: Streitwert bei 10,8 Milliarden Euro. Available at: https://www.gdv.de/gdv/medien/medieninformationen/abschlusszahlen-zum-diesel-skandal-streitwert-bei-10-8-milliarden-euro-162788

Guinea, O., Pandya, D., Sharma, V., Zilli, R. (2025). The Impact of Increased Mass Litigation in the UK. ECIPE, Brussels, occ. paper 6/2025, 78 p.

Guinea, O., Sharma, V., van der Marel, E., & du Roy, O. (2025). Breaking Barriers, Boosting Growth: Unlocking the Power of Digital Technology for Europe’s Competitiveness. ECIPE, Brussels, Policy Brief 14/2025, p. 27.

Independent UK. (2016, September 17). Volkswagen diesel emissions scandal: the toxic legacy. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/leading_business_story/volkswagen-diesel-emissions-scandal-the-toxic-legacy-a7312056.html

ITA. Germany Country Commercial Guide. Available at: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/germany-information-and-communications-technology-ict

Kempf, E., & Spalt, O. (2020). Attracting the sharks: Corporate innovation and securities class action lawsuits. Management Science, 69(3), 1805-1834.

Ministerial Drat (Referentenentwurf) of the Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection dated 11 September 2025. Available at: https://www.bmjv.de/SharedDocs/Gesetzgebungsverfahren/DE/2025_Produkthaftung.html

McKnight, D. L., & Hinton, P. J. (2024), Tort Costs in America: Third Edition. US Chambers of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform.

McKnight, D. L., & Hinton, P. J. (2011). Creating conditions for economic growth: the role of the legal environment. NERA Economic Consulting.

Morabito, V. (2019). An Evidence-Based Approach to Class Action Reform in Australia: Common Fund Orders, Funding Fees and Reimbursement Payments. Funding Fees and Reimbursement Payments (January 31, 2019).

Nindl, E., Confraria, H., Rentocchini, F., Napolitano, L., Georgakaki, A., Ince, E., Fako, P., Tuebke, A., Gavigan, J., Hernandez Guevara, H., Pinero Mira, P., Rueda Cantuche, J., Banacloche Sanchez, S., De Prato, G. and Calza, E., The 2023 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2023, doi:10.2760/506189, JRC135576

Office of Public Affairs, US Department of Justice. Available at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/volkswagen-spend-147-billion-settle-allegations-cheating-emissions-tests-and-deceiving

Plog, P. (2019, May 29). German draft law on legal tech: Take the plunge! Fieldfisher. Available at https://www.fieldfisher.com/en/insights/german-draft-law-on-legal-tech-take-the-plung

Verbraucherzentrale. Federal Association of Consumer Organizations is examining class action lawsuit against Avacon Natur GmbH. Available at: https://www.sammelklagen.de/verfahren/avacon

Volkswagen. (2020, February 28). VW to pay €830m settlement to German consumers. Available at: https://www.dw.com/en/dieselgate-volkswagen-to-pay-830-million-settlement-to-german-consumers/a-52572281

World Bank (2020). Doing Business in Europe. Accessed at: https://archive.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/media/Profiles/Regional/DB2020/EU.pdf