Privacy at a Price? An Empirical Analysis of GDPR’s Impact on EU Trade Flows

Published By: Elena Sisto Erik van der Marel

Research Areas: EU Single Market, Institutions, and Governance Trade, Globalisation and Security

Summary

The introduction of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2018 created conditions that could raise the cost of trading services with the EU, especially where cross-border transfers of personal data are required. This paper examines whether the GDPR has truly affected trade in digital services between EU member states and third countries.

Using a triple-difference strategy that compares EU trade with partners whose cross-border transfer regimes differ from the EU’s conditional model to a suitable control group, this paper accounts for the fact that, over time, many partners have adopted a similar conditional model (so-called spillovers), following the phenomenon known as the “Brussels effect.”

Identification relies on two elements: sectoral data intensity, measured by the share of firms in each sector participating in the EU-US Data Privacy Framework (DPF), and partner regime alignment, distinguishing EU-style conditional regimes from non-aligned regimes. We estimate a structural-gravity PPML model with high-dimensional fixed effects, complemented by robustness checks using input-output-based intensity measures and a non-gravity triple difference on growth.

Key results

- In addition to EU imports, the GDPR has also affected EU exports following its introduction in 2018.

- At the mean sectoral data intensity, EU imports are 8.19 percent lower and EU exports are 4.15 percent lower to partners with non-aligned transfer regimes after 2018.

- These negative effects are mainly caused by the data transfer mechanisms, which differ from those of the EU’s partners, rather than by its data protection regime.

- Effects rise with sectoral data intensity: at the 75th percentile, imports are 11.23 percent lower, and exports are 5.73 percent lower; at the 90th percentile, imports are 18.87 percent lower, and exports are 9.85 percent lower.

- The results are robust to how data intensity is measured as results are similar when replacing the DPF-based data intensity measure with the input-output measure.

- We also use a different modelling approach using a non-gravity triple-difference on trade growth (treated vs. control, pre- vs. post-2018), showing a similar pattern of slowdowns for partners with non-aligned transfer regimes.

Interpretation and implications: Notwithstanding the compliance costs that the GDPR imposes on firms regarding its data protection rules, differences in regulatory regimes for data transfers have an adverse effect on international trade in digital and data-reliant services.

Policy directions: (i) Deploy and scale up safeguard mechanisms for the international transfers of personal data between the EU and partners that are compatible and reduce trade cost frictions (e.g. shared transfer impact assessment checklists, pre-approved low-risk routes), (ii) Invest in expanding complementary low-friction channels, such as EU adequacy, to reduce compliance costs.

We thank Lars Vandelaar for excellent research assistance.

1. Introduction

In 2018, the European Union (EU) introduced the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), one of its major legislative frameworks governing the collection and use of personal data. The regulation aims to harmonise privacy standards across EU member states while strengthening individuals’ rights and control over their personal information in the EU market. Any domestic or foreign organisation that offers services to the EU market and processes the personal data of EU citizens is subject to the GDPR and may therefore affect trade.

The GDPR has an extraterritorial scope, extending its application beyond the EU’s geographical borders to include any organisation that collects or processes the personal data of EU citizens, regardless of where the organisation is located. Firms without a physical presence or legal establishment in the EU are nevertheless required to comply with the regulation if they handle data belonging to EU citizens. This extraterritorial reach is likely to shape the range of services that foreign providers offer to the EU market, thereby directly influencing their export activities. In addition, the privacy requirements may affect the organisation of digital supply chains for both domestic and foreign firms operating within the EU, with broader implications for the services that the EU itself provides to foreign markets. This paper empirically assesses the impact of the EU’s GDPR on both imports and exports in digital services.

However, over the years, many other countries have adopted data protection regulations similar to those of the EU. Such spillover effects pose a common challenge in the empirical literature assessing the economic impact of the GDPR, as they complicate the identification of a suitable control group of EU partner countries unaffected by the regulation.[1] This paper employs a triple-difference approach to construct such a control group. Our identification strategy rests on the assumption that partner countries with data protection frameworks substantially different from the EU’s model incur higher costs when trading services with the EU market. Following Ferracane and van der Marel (2025), Aaronson and Leblond (2019), and Bradford (2023), the GDPR can be characterised as a rights-based approach to data protection, establishing conditions under which EU citizens’ data may be processed or transferred to third countries.[2] Partner countries that lack such a conditional framework, or that have no specific data protection regulations, face greater challenges in meeting the administrative requirements of the GDPR, thereby constraining their ability to trade services with EU member states.

Moreover, our triple-difference approach further isolates time-invariant, sector-level trends in services trade. In doing so, we introduce a firm-level-based, sector-varying variable that measures the extent to which firms active in each service sector are considered reliant on EU personal data. This data-intensity measure is then interacted with our control-group variable, which captures whether EU partner countries apply a substantially different regulatory framework for data protection. The underlying assumption is that firms operating in sectors with greater data dependence and located in partner countries with markedly different data governance models, will find it disproportionately more difficult than the average firm to trade digital services with the EU after the introduction of the GDPR. To construct this triple interaction term, we use data covering 15 service sectors and 137 partner countries worldwide, ranging from high-income to low-income economies, over the period 2010-2023.

The gravity results of our methodology show that EU imports of data-intensive services declined significantly following the introduction of the GDPR in 2018. Interestingly, EU exports of these services also experienced a marked decrease. A series of robustness checks, including a non-gravity triple-difference approach, confirms this negative impact on both imports and exports, showing in addition a significant reduction in the growth rate of EU digital services trade pre- and post-GDPR. Our results remain robust when employing alternative sector-level data-intensity measures based on input-output tables and by accounting for the fact that some countries were granted adequacy decisions by the EU, removing the need to introduce safeguard measures for cross-border data transfers.[3]

It is important to note that our control group variable captures differences in data governance models based on rules related to personal data transfers. However, data governance models also include provisions concerning data protection, for which we develop a separate variable in our control group that is not part of the baseline control definition. This second variable measures whether partner countries’ data protection regimes differ from the GDPR. Incorporating this second measure as a robustness check into our regressions yields no statistically significant results, thereby serving as an implicit falsification test. This suggests that the negative effects identified in this paper are driven by differences in how the GDPR regulates cross-border data transfers, rather than by differences in domestic requirements governing the processing of personal data.

Related literature. The economic literature has recently produced several important empirical contributions to which our paper relates. First, a growing body of research has assessed the GDPR’s impact on various economic outcomes, including data usage, firm profitability, and venture capital. Frey and Presidente (2024) find that the GDPR negatively affected the short-term profitability of firms in digital sectors, indicating significant compliance costs.[4] Demirer et al. (2024) show that the GDPR reduced firms’ capacity to develop data-based activities, such as data collection and processing.[5] Jia et al. (2021) demonstrate that the GDPR adversely affected the number of EU venture deals, particularly between the EU and the US, due to a shift in investment strategies toward closer deals–especially in data-intensive ventures, a finding reinforced by Jia et al. (2025).[6] Finally, Goldberg et al. (2024) show that the GDPR affected data-based services themselves, such as online web traffic, leading to declines in firms’ revenues.[7]

Second, our work also relates to an emerging strand of the empirical literature that categorises regulatory frameworks for digital market activities in general, and for personal data in particular. Bradford (2023), for example, distinguishes three regulatory governance models that shape firms’ standards on digital activities and technologies such as AI: a rights-based approach (EU), a largely unregulated approach (US), and an authoritarian approach (China).[8] Earlier, Aaronson and Leblond (2021) had already outlined this tripartite distinction for data governance.[9] Building on these contributions, Ferracane and van der Marel (2025) classify countries into each of the three categories and assess their effects on digital trade, showing that the adoption of EU-style conditional flow regimes has mixed effects on trade in digital services.[10]

Third, our paper also relates to a broader strand of the services literature that examines how data-related regulations affect firm-level productivity, trade, and employment. Studies such as Ferracane and van der Marel (2021), Ferracane et al. (2020), and Cusolito et al. (2025) document negative effects on these outcomes, respectively.[11] Given that data-related policies primarily affect digital activities which are found in services, owing to their reliance on data and cross-border data flows, our work also connects to the empirical literature on the impact of services regulation more generally on trade and productivity.[12] Notably, these latter contributions employ interaction terms between industry-level intensity measures and country-level regulatory indicators, a strategy that closely resembles our own empirical approach.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. The next section describes the data used for the empirical analysis. Section 3 outlines the empirical specification, which employs a gravity model and develops our triple-difference approach. Section 4 presents the gravity results and a set of robustness checks, including a non-gravity-based triple-difference approach. Finally, Section 5 concludes and discusses several policy implications.

[1] Johnson, G. (2022). Economic research on privacy regulation: Lessons from the GDPR and beyond (NBER Working Paper No. 30705). National Bureau of Economic Research.

[2] Ferracane, M. F., & van Der Marel, E. (2025). Governing personal data and trade in digital services. Review of International Economics, 33(1), 243-264; Aaronson, S. A., & Leblond, P. (2018). Another digital divide: The rise of data realms and its implications for the WTO. Journal of International Economic Law, 21(2), 245-272; Bradford, A. (2023). Digital empires: The global battle to regulate technology. Oxford University Press.

[3] Ferracane, M. B., Hoekman, B., Santi, F., & van der Marel, E. (2025). Digital trade, data protection and the EU adequacy club. Economica. Forthcoming.

[4] Frey, C. B., & Presidente, G. (2024). Privacy regulation and firm performance: Estimating the GDPR effect globally. Economic Inquiry, 62(3), 1074-1089.

[5] Demirer, M., Hernández, D. J. J., Li, D., & Peng, S. (2024). Data, privacy laws and firm production: Evidence from the GDPR (No. w32146). National Bureau of Economic Research.

[6] Jia, J., Jin, G. Z., & Wagman, L. (2021). The short-run effects of the general data protection regulation on technology venture investment. Marketing Science, 40(4), 661-684; Jia, J., Jin, G. Z., Leccese, M., & Wagman, L. (2025). How Does Privacy Regulation Affect Transatlantic Venture Investment? Evidence from GDPR (No. w33909). National Bureau of Economic Research.

[7] Goldberg, S. G., Johnson, G. A., & Shriver, S. K. (2024). Regulating privacy online: An economic evaluation of the GDPR. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 16(1), 325-358. See for a complete literature review on the effects of measuring the economic impact of the GDPR the work by Johnson (2022) which also discusses the challenges that papers face in measuring the regulation.

[8] Bradford, A. (2023). Digital empires: The global battle to regulate technology. Oxford University Press.

[9] Aaronson, S. A., & Leblond, P. (2018). Another digital divide: The rise of data realms and its implications for the WTO. Journal of International Economic Law, 21(2), 245-272.

[10] Ferracane, M. F., & van Der Marel, E. (2025). Governing personal data and trade in digital services. Review of International Economics, 33(1), 243-264. Other significant economic, policy and legal works that use this distinction between the three regulatory governance models for data include World Bank (2021), Ferracane and van der Marel (2021), Gao (2018).

[11] Van der Marel, E., & Ferracane, M. F. (2021). Do data policy restrictions inhibit trade in services?. Review of World Economics, 157(4), 727-776; Ferracane, M. F., Kren, J., & Van Der Marel, E. (2020). Do data policy restrictions impact the productivity performance of firms and industries?. Review of International Economics, 28(3), 676-722; Cusolito, A., van der Marel, E., Nayyar, G., & Pleninger, R. (2025). Data flows restrictiveness and (un)equal productivity and jobs effects. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. Forthcoming.

[12] Barone, G., & Cingano, F. (2011). Service regulation and growth: evidence from OECD countries. The Economic Journal, 121(555), 931-957; Arnold, J., Javorcik, B., & Mattoo, A. (2006). The productivity effects of services liberalization: Evidence from the Czech Republic. World Bank working paper, 1-38; Arnold, J. M., Javorcik, B., Lipscomb, M., & Mattoo, A. (2016). Services reform and manufacturing performance: Evidence from India. The Economic Journal, 126(590), 1-39; van der Marel, E. (2016). Ricardo does services: Service sector regulation and comparative advantage in goods. In Research handbook on trade in services (pp. 85-106). Edward Elgar Publishing; Beverelli, C., Fiorini, M., & Hoekman, B. (2017). Services trade policy and manufacturing productivity: The role of institutions. Journal of international economics, 104, 166-182.

2. Data

As part of our identification strategy to assess the impact of the EU’s GDPR on data-reliant services trade, we use three datasets: (1) partner countries’ regulatory governance models for cross-border transfers and data protection; (2) sector-level measures of reliance on personal data; and (3) bilateral services trade data.

2.1 Regulatory Data Models

Our first dataset contains information on how countries have developed their regulatory governance framework to control the processing and cross-border transfers of personal data by firms. With this information at hand, we are able to assess whether partner countries apply substantially different data protection regimes compared to the EU’s GDPR. This data is key in developing an appropriate control group. Many previous studies examining the economic effects of the GDPR adopt an event study framework, as we do; however, they are often limited by the lack of a suitable control group.[1] This limitation arises from two spillover channels, which so far the literature has been unable to capture, namely, first, the direct effect of the GDPR itself on firms outside the EU on how they need to deal with EU personal data and, second, the EU’s capacity to “export” its data protection standards globally, commonly referred to as the “Brussels effect”.[2]

The data on regulatory models for personal data are drawn from the database developed by Ferracane and van der Marel (2025).[3] This dataset documents how countries have designed rules governing cross-border transfers and the protection of personal data. We focus on regulations governing cross-border transfers, as the literature identifies policies related to the cross-border mobility of data as one of the most critical regulatory concerns for digital technologies and international trade.[4] The dataset classifies 150 countries into one of three models for regulating personal data transfers, following the distinction made by World Bank (2021), Aaronson and Leblond (2021) and Bradford (2023), which are (1) an open transfer model, (2) a conditional transfer model, and (3) a controlled transfer model.[5]

The open model, led by the US, is characterised by the absence of restrictions on cross-border data flows and the lack of a regulatory framework governing the domestic processing of personal data. Countries following this model typically rely on a basic set of privacy principles for cross-border data transfers, granting firms considerable flexibility to self-regulate on a voluntary basis. While firms are generally expected to remain accountable for the handling of personal data, including their transfer to third-country recipients, in practice, many countries following the open model lack effective mechanisms to ensure accountability once data has crossed national borders. Countries without any regulations in place are also categorised under this model.

The conditional model, pioneered by the EU, is characterised by the imposition of specific regulatory conditions on the transfer and processing of personal data. Countries adhering to this model adopt a comprehensive, rights-based approach to data protection, grounded in preventative regulation. With respect to cross-border data transfers, this model requires certain ex-ante conditions to be met before personal data may be transferred internationally. These conditions may include obtaining the explicit consent of the data subject, adhering to approved codes of conduct, or employing specific legal safeguards such as Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs) and Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs). They may also include ensuring that the recipient country maintains a data protection regime deemed “adequate” by the relevant authorities. Under the GDPR, firms are required to comply with these conditions.

These contractual mechanisms enable firms to demonstrate compliance with the GDPR. However, they are often costly due to the complex and burdensome approval procedures involved.[6] The associated costs include both fixed and variable components. Beyond implementing the necessary contractual safeguards, firms may need to hire data protection specialists or consultancy services for tasks such as data mapping, compliance management, and third-party auditing. These costs vary depending on factors such as the number of countries involved in the supply chain, the nature of the data transfers, and the specific processing activities. For example, SCCs must be revised and re-executed whenever the nature of personal data processing changes.[7] In the case of BCRs, data transfers must be approved by the Data Protection Authority of the EU member state in which the firm or its subsidiary is established.

The third model, exemplified by China, is based on the controlled transfer and processing of personal data without strong data privacy regulations. In such contexts, data privacy is often closely linked to cybersecurity, with data regulation framed primarily as a matter of national security with little transparency for data privacy.[8] Moreover, governments are able to access personal data held inside the country’s territory without a court order, including data from third countries. Countries adopting this model are characterised by extensive restrictions on cross-border data flows and by the centralised oversight of personal data by state authorities. With respect to international data transfers, this model typically imposes strict requirements, including mandatory local processing of data and the need for prior governmental authorisation following a security assessment before data may be transferred abroad.

A summary of the characteristics of each data governance model is provided in Table A1 in the annex. Figure A1 illustrates how the global distribution of countries adopting a specific data model has shifted significantly over the past three decades. Most countries have adopted an EU-style governance framework with nonetheless still a sizable minority of countries, accounting for 36 percent, that have adopted either the open or government-controlled model. In terms of trade, these countries nonetheless represent 52 percent of the EU’s total imports of services.

With this data, we can directly assess how firms outside the EU are required to comply with personal data transfer regulations, an essential condition for trading data-based services with the EU, given the safeguards imposed with each transfer. This allows us to capture the first spillover effect. The underlying assumption is that firms operating in countries without a conditional transfer regime similar to the EU’s face higher transaction costs in implementing the cross-border safeguards, thereby increasing trade costs for firms when exporting their services to EU members.

In addition, the dataset records the application of the three models of personal data transfers for each country over time, identifying the year in which countries shifted from an open model to either a conditional or controlled model. This feature enables us to capture the second spillover effect, namely when countries began to implement standards aligned with those of the EU, a phenomenon often referred to in the broader literature as the “Brussels effect.” Countries with similar conditions in place are likely to face lower transaction costs in complying with EU regulations, making it easier for them to trade.

Of note, given the time dimension of this variable it allows us, to the extent possible, to account for untreated units (i.e., those that have a conditional model) being systematically different from treated units (i.e., those that are under, or move into, an open or controlled model) before and after the GDPR entered into force within our panel. This wouldn’t be possible with such data for one year only at the time of the introduction of the GDPR. This therefore helps to reduce potential biases arising from issues such as policy targeting, pre-treatment trends, or selection bias.

2.2 Data-Intensities

Our second dataset measures the extent to which service industries rely on cross-border personal data flows. This information captures the industry-level exposure of data-reliant trade to the EU market. As previously noted, identifying a suitable control group for GDPR studies is particularly challenging, and prior research has often relied on identification strategies based solely on such industry-level intensity measures.[9] In our empirical approach, discussed in more detail below, we build on this strategy by combining industry-level intensity measures with our variable capturing countries’ regulatory governance frameworks.

Specifically, we construct two measures of data intensity. The first is derived from firm-level information related to participation in the EU-US Data Privacy Framework (DPF) agreement. This agreement facilitates transatlantic trade by providing US firms with a specific mechanism for personal data transfers from the EU to the US consistent with European law.[10] The US Department of Commerce maintains a registry of self-certified companies, which includes details on each firm’s primary sector of activity. Using web scraping techniques, we collected data on all 2,675 companies certified under the DPF, including their primary and sub-sector classifications, as well as the stated purposes for which they utilise the adequacy framework. We use this information to compute a sector-level measure of data intensity, based on the share of self-registered certified firms within each sector.[11]

The second data-intensity variable is constructed from national input-output tables provided by the OECD, based on 2-digit ISIC Rev. 4 classification. It defines data intensity as the extent to which downstream sectors rely on upstream digital services. This upstream-downstream distinction allows us to account for the fact that even non-digital sectors may be affected by the GDPR through their dependence on digital inputs. We distinguish between two measures: domestic input elasticities, reflecting the use of domestically sourced digital inputs, and cross-border input elasticities, capturing reliance on imported digital inputs.

To compute the digital input-output measures, we identify the following upstream digital sectors that supply inputs to downstream industries: Publishing, Audio-Visual and Broadcasting (ISIC D58T60); Telecommunications (ISIC D61); and Information Technology and Other Information Services (ISIC D62T63). For each downstream sector, we calculate the share of inputs sourced from these digital sectors relative to the sector’s total intermediate consumption (at purchasers’ prices). The sum of both domestic and imported input shares is the total value of digital inputs used by each downstream sector.

Our preferred measure of data intensity is based on firm-level participation in the DPF. However, due to potential self-selection of firms already reliant on cross-border data in the agreement, we use the input elasticities as a robustness check, we employ the input elasticity, which aligns with the input-output coefficient used in Frey and Presidente (2024). Their input measure, however, captured the import elasticities, which in our case may also raise endogeneity concerns since our dependent variable is cross-border trade. We therefore prefer to use domestic input elasticities. To further mitigate endogeneity concerns, we compute these elasticities as the cross-country average from the 2010 input-output tables, a year that precedes the implementation of the GDPR by almost a decade.

2.3 Trade in Services

Trade in services data is sourced from the WTO-OECD BaTIS database, which reports trade flows in gross terms. While this database offers several advantages, it also presents certain limitations relative to alternative data sources, as discussed in this section.

The WTO-OECD BaTIS database offers the significant advantage of providing coverage for nearly all countries worldwide, including a broad range of developing economies. Moreover, it reports trade in services data up to 2023, a notably longer time span compared to other available datasets. Given our focus on the longer-term trade effects of the GDPR–as opposed to the short-term impacts examined in much of the existing literature–this extended coverage is key for our analysis[12] However, many trade flows for these countries are estimated using various statistical techniques, ranging from simple methods like mirroring to more complex parametric estimates based on the gravity model. Additionally, the database covers fewer service sectors, only 11, compared to other databases such as TiVA.

Although many observations in the BaTIS database are estimated, another advantage is that this data source distinguishes between inferred and reported trade values, allowing researchers to isolate observations based solely on reported data. Furthermore, given the well-documented idiosyncrasies and inconsistencies in reported services trade data, the database applies adjustments to outliers to produce “balanced” trade values in a squared matrix format. We follow the recommended approach by using reported values in our baseline analysis but also report results based on balanced values in our robustness checks.

[1] Johnson, G. (2022). Economic research on privacy regulation: Lessons from the GDPR and beyond (NBER Working Paper No. 30705). National Bureau of Economic Research.

[2] Bradford, A. (2020). The Brussels effect: How the European Union rules the world. Oxford University Press.

[3] Ferracane, M. F., & van Der Marel, E. (2025). Governing personal data and trade in digital services. Review of International Economics, 33(1), 243-264.

[4] Goldfarb, A., & Trefler, D. (2018). AI and international trade (No. w24254). National Bureau of Economic Research; Sun, R., & Trefler, D. (2023). The impact of AI and cross-border data regulation on international trade in digital services: A large language model (No. w31925). National Bureau of Economic Research.

[5] World Bank. (2021). World development report 2021: Data for better lives. World Bank; Aaronson, S. A., & Leblond, P. (2018). Another digital divide: The rise of data realms and its implications for the WTO. Journal of International Economic Law, 21(2), 245-272; Bradford, A. (2023). Digital empires: The global battle to regulate technology. Oxford University Press.

[6] Cory, N., Castro, D., & Dick, E. (2020a). ‘Schrems II’: What Invalidating the EU-US Privacy Shield Means for Transatlantic Trade and Innovation. Information Technology and Innovation Foundation; Cory, N., Dick, E., & Castro, D. (2020b). The role and value of standard contractual clauses in EU-US digital trade. Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

[7] Chivot, E., & Cory, N. (2020). Response to European Commission Consultation on Transfers of Personal Data to Third Countries and Cooperation Between Data Protection Authorities. The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, April, 29.

[8] Gao, H. (2018). Digital or trade? The contrasting approaches of China and US to digital trade. Journal of International Economic Law, 21(2), 297-321.

[9] Frey, C. B., & Presidente, G. (2024). Privacy regulation and firm performance: Estimating the GDPR effect globally. Economic Inquiry, 62(3), 1074-1089.

[10] The DPF has been extended to include the UK (UK Extension to the EU-U.S. DPF), as well as Switzerland with the Swiss-U.S. Data Privacy Framework (Swiss-U.S. DPF).

[11] While the DPF was established in 2023, the list of participating firms builds on the two previous EU–US data agreements: Safe Harbor (2000 – 2015) and the EU-US Privacy Shield (2016 – 2020). The assumption is that these firms remain the same. However, due to the possibility of endogeneity–for example, if the list of firms expanded substantially after 2018, which we cannot verify–we also employ an additional intensity measure as a robustness check.

[12] The TiVA database provides trade in services data covering the period from 1995 to 2020, which is too short to derive any meaningful outcomes given that the GDPR was only introduced three years before. A third source for trade in services is the ITPD-E database. However, the database also covers a shorter time frame, spanning only from 2000 to 2019. Moreover, many trade values for these countries are unreported, leading to significant gaps in the data. Both BaTIS and TiVA are provided in balanced squared format.

3. Empirical Specification

This section sets out the main empirical specification to estimate the impact of the GDPR on trade in services. It employs a standard gravity model incorporating a triple difference framework, while as part of our robustness checks below this triple-difference approach will be used in a non-gravity framework.

The gravity model is a widely used framework for analysing the determinants of bilateral trade flows, including policy variables, such as the GDPR in our case.[1] In applying the gravity model, we assume that bilateral trade follows a Poisson distribution to account for instances of zero trade observations, following Santos Silva and Tenreyro (2006, 2011).[2] As noted above, we focus on bilateral trade in services, which have increasingly been analysed using gravity models.[3]

Given that the GDPR applies to all companies using EU citizens’ data, it affects industries and sectors beyond those typically classified as digital. This paper therefore employs a gravity model that pools trade data across all service sectors, following works by French (2017)[4], French and Zylkin (2024)[5], and Brunel and Zylkin (2022).[6] This method addresses potential aggregation bias among the treated sectors and controls for bilateral time-variant unobserved factors that may influence bilateral trade. Pooling across sectors allows us to capture not only the temporal variation in countries’ adoption of the GDPR but also the trade variation induced by the GDPR across all service sectors. This approach is comparable to estimating an average treatment effect rather than conducting sector-by-sector estimations or calculating an average treatment effect limited to treated sectors.

3.1 Variable of Interest

However, the trade impact of the GDPR is not equally felt across sectors, as some rely more on the EU’s personal data than others, as previously explained. To account for this pattern, our empirical specification makes use of an interaction term in which the GDPR variable between EU members and partner countries is interacted with the two sector-weighted proxies of data-intensities, Ik, so that: [7]

(1) GDPREUdt= Ik * OTHEUdt * 1{t ≥2018}

in which the GDPREUdt varies between EU countries (including EEA members for which the GDPR also applies) and all non-EU trading partners d, by service sectors k, and finally by year t.

The term Ik measures firm-level exposure to data-reliant trade, which is our first variable of data-intensity. As described above, it captures for each services sector the share of firms subscribed to the DPF framework. In doing so, we must manually map each DPF-registered firm by its registered sub-sector classification into the EBOPS trade classification, which is non-aligned and much more aggregated. This concordance process may therefore introduce some degree of measurement error. To mitigate potential bias, we compute both the mean and median across all DPF-reported sub-sectors. A sector is classified as data-intensive by a dummy that equals 1 if its value exceeds the average or median threshold. We also use two continuous measures of data intensity based on the actual sectoral shares, one derived from the mean and one from the median, accounting for a fuller variation of data intensity across sectors.[8]

Additionally, given that we can identify a suitable control group, we interact this term with a second dummy variable indicating whether a partner country has a substantially different personal data transfer regime than the EU, denoted as OTHEUdt, which as previously said, varies for each partner country over time.

By separating partner countries which follow a different data governance framework, we can isolate those countries to which the EU has effectively exported its data transfer standards over the years, using them as a control group. From a regulator’s perspective this matters. Under a conditional flow regime, safeguard measures that companies fill in and implement need to be accepted by the relevant approving authority.[9] An important factor in these protective measures is that the company using these safeguards must ensure an adequate level of data protection in the third country where the “data-importer” (i.e., firm in the partner country) resides.

Partner countries which have implemented a conditional framework for cross-border data flows similarly require domestic companies to establish safeguards to protect the privacy of their citizens, requirements that are not imposed in countries without such frameworks. As a result, firms in these countries, already experienced with implementing safeguard measures, face relatively lower costs when complying with the EU’s requirements for handling its citizens’ data in the context of exports to the EU. Countries operating under open or government-controlled data models lack any such safeguard measures.

For example, under the use of SCCs, companies are required to assess whether the national laws of the partner country (i.e., third country) are compatible with the obligations outlined in the SCCs for personal data transfers. If this assessment–referred to as a Transfer Impact Assessment (TIA)–reveals any privacy risks stemming from the legal framework of the recipient country, companies must implement additional obligations to ensure adequate protection in line with the GDPR. These additional regulatory measures can range between technical measures such as encryption and pseudonymisation, which in practice are difficult to implement for data processors; or contractual and organisational measures, such as strict internal legal guidelines for data access and confidentiality or access rights. The regulatory agency may also require a contractual arrangement in which a partner country is denied data access altogether. These additional safeguard measures make compliance significantly more burdensome for firms operating in countries with data governance frameworks that are not aligned with the EU’s standards.

Moreover, the risk of receiving fines post-approval for violating the requirement of an adequate level of data protection under SCCs is significantly higher for countries with non-aligned regulatory frameworks. Notably, among the top ten fines issued by EU Data Protection Authorities for GDPR non-compliance, none were levied against companies based in countries that follow the EU’s data governance model.[10]

Because the OTHEUdt term varies by year, the empirical specification accounts for the timing of countries transitioning to a conditional data transfer model. We therefore control for the spill-over effects over time. This time dimension reduces any upward bias in our specification as several countries switched from an open model to either a conditional model or a government-controlled model. When countries shift to a conditional model, such transitions alter the potential cost structure of data transfers, thereby influencing firms’ ability to export digital services to the EU market. Furthermore, we measure this effect only for the period following the implementation of the GDPR in 2018, two years after the regulation was adopted and the year it became legally enforceable. To capture this timing, we multiply the interaction term by a dummy variable that takes the value of 1 from 2018 onward, i.e. 1{t ≥2018}.

3.2 Estimated Regressions for Imports and Exports

Finally, to measure the effect of the GDPR on trade, we regress the following specification:

(2) IModtk=exp{β1GDPREUdkt+αokt+γdkt+δodt+θodk}+εodkt

where IModtk represents imports and the GDPREUdk is plugged in from equation (1) above.

Note that in this setting our variable of interest effectively becomes a triple interaction term, or a three-way-interaction variable, and therefore our specification becomes a triple-difference approach: one difference representing the trade effect of partner countries with a substantially different data governance model than the EU compared to those which followed the EU’s conditional data model, the second difference reflecting the impact on sectors classified as data-intensive, and third difference between two periods of time, i.e. before and after the EU’s implementation of the GDPR. Essentially, equation (2) estimates whether the interaction between the treatment and data-intensity of sectors depends on whether countries follow the EU’s conditional data model or not.[11]

General changes that may affect IModtk due to changes in trade costs of EU members that simultaneously affect trade with all its trade partners across all sectors are absorbed by the set of fixed effects. In particular αokt, γdkt, δodt and θodk represent, in respective order, the origin-sector-time, partner-sector-time, and origin-partner-time, and origin-partner-sector fixed effects. Notice that the term δodt absorbs all standard gravity controls, such as the distance between partner countries, having a PTA in place, or membership in the WTO. Finally, εodkt represents the error term and standard errors are three-way clustered by partner, sector and year following Egger and Tarlea (2015).[12] Our panel covers the period 2010-2023.

Additionally, equation (2) estimates the effect of the introduction of the GDPR on the EU’s imports, which correspond to partner countries’ exports to the EU market. This trade effect is intuitive, as foreign firms often process the personal data of EU citizens when it is transferred to partner countries that provide digital services back to the EU. However, the GDPR is also likely to impact the EU’s own exports.

For example, the GDPR’s privacy regulations may make it more difficult for companies to train AI models, which require large and diverse datasets, often sourced internationally, to function effectively. As a result, firms in the EU may choose to relocate parts of their operations outside the EU, potentially reducing exports.[13] Moreover, the GDPR applies not only to data concerning EU citizens but also to all personal data processed within the EU market. This broad scope can hinder the collection and combining of large datasets necessary for AI and other digital technologies. Even when data is held within national borders, compliance costs may render processing prohibitively expensive. Firms may opt to shift parts of the value chain, such as software engineering or data analytics, to lower-cost jurisdictions, not necessarily to avoid the GDPR, but to offset the associated compliance burden. For these reasons, we also regress equation (2) using exports (EXodtk) as our dependent variable.

[1] Head, K., & Mayer, T. (2014). Gravity equations: Workhorse, toolkit, and cookbook. In Handbook of international economics (Vol. 4, pp. 131-195). Elsevier.

[2] Silva, J. S., & Tenreyro, S. (2006). The log of gravity. The Review of Economics and statistics, 641-658; Silva, J. S., & Tenreyro, S. (2011). Further simulation evidence on the performance of the Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimator. Economics Letters, 112(2), 220-222.

[3] Anderson, J. E., Borchert, I., Mattoo, A., & Yotov, Y. V. (2018). Dark costs, missing data: Shedding some light on services trade. European Economic Review, 105, 193-214.

[4] French, S. (2017). Comparative advantage and biased gravity. UNSW Business School Research Paper, (2017-03).

[5] French, S., & Zylkin, T. (2024). The effects of free trade agreements on product-level trade. European Economic Review, 162, 104673.

[6] Brunel, C., & Zylkin, T. (2022). Do cross‐border patents promote trade?. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique, 55(1), 379-418. Baier and Bergstrand (2007) use these three-way fixed effects to estimate the impact of trade agreements on trade, whereas Brunel and Zylkin (2022) use this structure to assess the impact of cross-border patent fillings on trade. See French (2017) for further discussion on this topic.

[7] This approach builds on a long-standing stream of research initiated by Rajan and Zingales (1998). Other papers that use industry-level input intensity measures computed using input-output tables and which are interacted these with policy variables include Bourles et al. (2013), Arnold et al. (2011; 2016) and Beverelli et al. (2017). See Ciccone and Papaioannou (2023) for a review of this literature.

[8] When using the shares, this approach is analogous to a “shift-share” variable, in which the estimated coefficient captures the shift–that is, the change in trade outcomes before and after the implementation of the GDPR–while the sector-specific exposure represents the share component.

[9] For Binding Corporate Rules this is the Data Protection Authority of the relevant EU member country where the company has its main EU establishment (art. 47 GDPR), while that for Standard Contractual Clauses this is the European Commission (Article 46(2)(c) and (d) of the GDPR).

[10] For more information, see the GDPR Enforcement Tracker, which is maintained by the CMS law firm: https://www.enforcementtracker.com/

[11] Note that by incorporating a control group such triple difference approach incidentally also accounts for unobservable interactions between group- and time-characteristics that might otherwise not be captured with a standard difference-in-difference (DiD) framework. Moreover, in a DiD setting, the EU’s policy change to the GDPR would cause any trade changes irrespective of the EU’s trading partner. This would assume that the trade outcomes for data-intensive services between the EU and partner countries applying a different model would not be systematically different in the absence of intervention. We argue that due to these spill-over effect, this is not the case.

[12] Egger, P. H., & Tarlea, F. (2015). Multi-way clustering estimation of standard errors in gravity models. Economics Letters, 134, 144-147. Notice further that when applying our dummy of in equation (2) the estimated effect is an average treatment effect of the treated (ATT), i.e., data-intensive sectors. When we use the continuous shares, accounting for the full variation in data intensities across all sectors, the outcome implies an average treatment effect (ATE).

[13] Some companies may even redesign their offerings to minimise personal data use entirely by for example moving from individual-level tracking to aggregate-level insights, which in turn may influence their international deployment strategy of their data-reliant services. Other examples include the placement of data centres in the EU that may become more costly because of the GDPR, which may prompt investors to locate centres outside the EU, similarly depriving the EU from export revenue.

4. Results

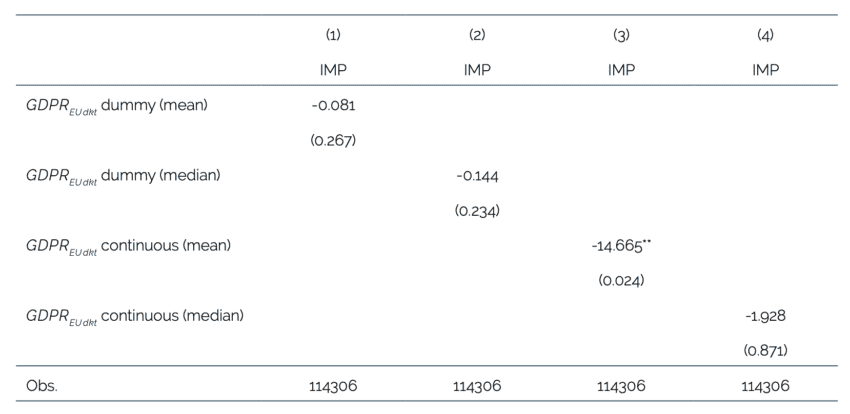

The regression results of equation (2) are reported in Table 1 and Table 2 for imports and exports, respectively. For imports, the results are negative and significant in only one out of four specifications. Columns (1) and (2) present results using dummy variables for our data-intensity measure, based on the mean and the median thresholds, respectively. Both yield insignificant results, although with a negative coefficient sign. Columns (3) and (4) report results using continuous measures of data intensity, based on shares relative to the mean and median. Here, significance is observed only when using the mean.

Table 1: Baseline results following equation (2) for imports Note: * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01. GDPREUdtk is the triple-difference variable, defined as the interaction of 1{t ≥2018} (the GDPR period indicator), the data-intensity variable Ik based on the EU–US DPF, and OTHEUdt, which denotes partner countries with a regulatory regime for cross-border data transfers different from that of the EU. “Dummy” refers to the use of a binary indicator for , while “continuous” refers to the use of sectoral shares. The regressions include origin-sector-time, destination-sector-time, origin-destination-sector, and origin-destination-time fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the origin, destination, and time level.

Note: * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01. GDPREUdtk is the triple-difference variable, defined as the interaction of 1{t ≥2018} (the GDPR period indicator), the data-intensity variable Ik based on the EU–US DPF, and OTHEUdt, which denotes partner countries with a regulatory regime for cross-border data transfers different from that of the EU. “Dummy” refers to the use of a binary indicator for , while “continuous” refers to the use of sectoral shares. The regressions include origin-sector-time, destination-sector-time, origin-destination-sector, and origin-destination-time fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the origin, destination, and time level.

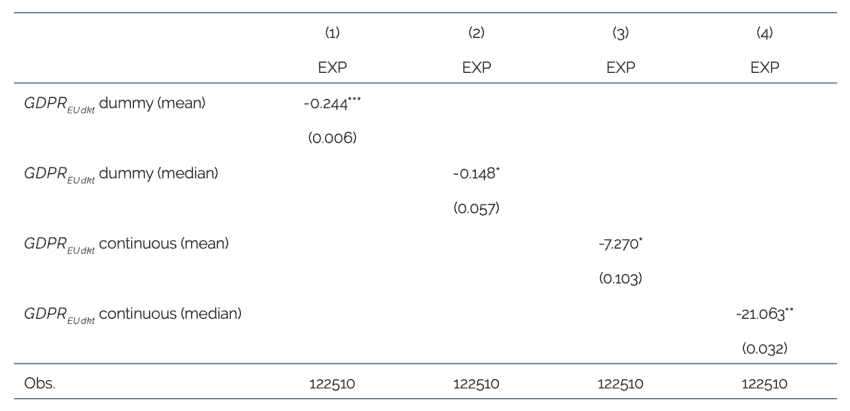

The export results also show a negative and significant coefficient across all four specifications, with the most significant effect in column (1), which uses the dummy based on the mean threshold.

Table 2: Baseline results following equation (2) for exports Note: * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01. GDPREUdtk is the triple-difference variable, defined as the interaction of 1{t ≥2018} (the GDPR period indicator), the data-intensity variable Ik based on the EU–US DPF, and OTHEUdt, which denotes partner countries with a regulatory regime for cross-border data transfers different from that of the EU. “Dummy” refers to the use of a binary indicator for Ik, while “continuous” refers to the use of sectoral shares. The regressions include origin-sector-time, destination-sector-time, origin-destination-sector, and origin-destination-time fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the origin, destination, and time level.

Note: * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01. GDPREUdtk is the triple-difference variable, defined as the interaction of 1{t ≥2018} (the GDPR period indicator), the data-intensity variable Ik based on the EU–US DPF, and OTHEUdt, which denotes partner countries with a regulatory regime for cross-border data transfers different from that of the EU. “Dummy” refers to the use of a binary indicator for Ik, while “continuous” refers to the use of sectoral shares. The regressions include origin-sector-time, destination-sector-time, origin-destination-sector, and origin-destination-time fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the origin, destination, and time level.

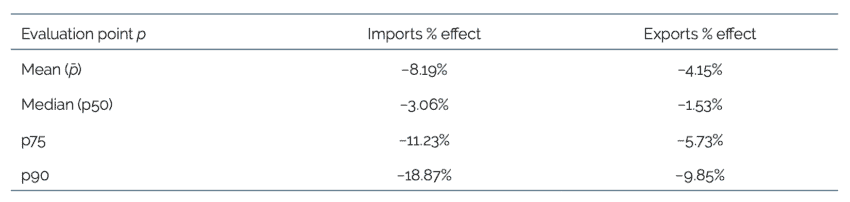

Evaluated at the mean DPF intensity (p=pˉ), based on the continuous measure, the implied treated-vs-control gap equals -8.19 percent for imports and -4.15 percent for exports, as shown Table 3. The effect grows with higher levels of intensity: at p75 the gap reaches -11.23 percent for imports and -5.73 percent for exports, and at p90 the difference becomes -18.87 percent and -9.85 percent, respectively.

Table 3: Implied effects at representative DPF intensities (continuous-mean specification) Note: Effects are computed as 100(exp[β ̂⋅p]-1 using the continuous (mean) coefficients from Table 2 col. (3) [imports] use and Table 3 col. (3) [exports]. Imports use β ̂IMP =-14.665; exports use β ̂EXP =-7.270

Note: Effects are computed as 100(exp[β ̂⋅p]-1 using the continuous (mean) coefficients from Table 2 col. (3) [imports] use and Table 3 col. (3) [exports]. Imports use β ̂IMP =-14.665; exports use β ̂EXP =-7.270

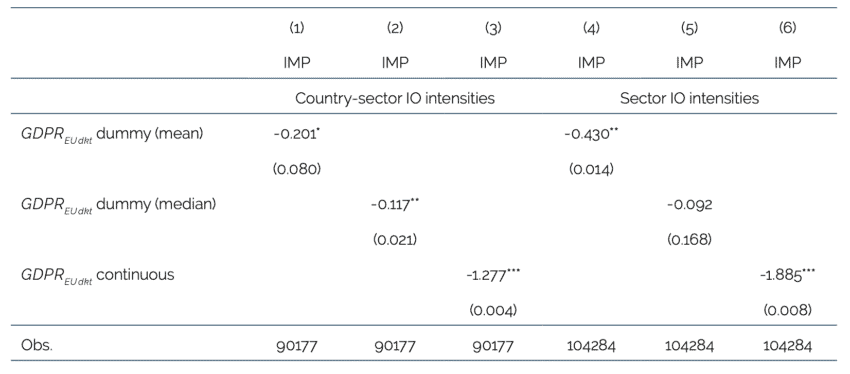

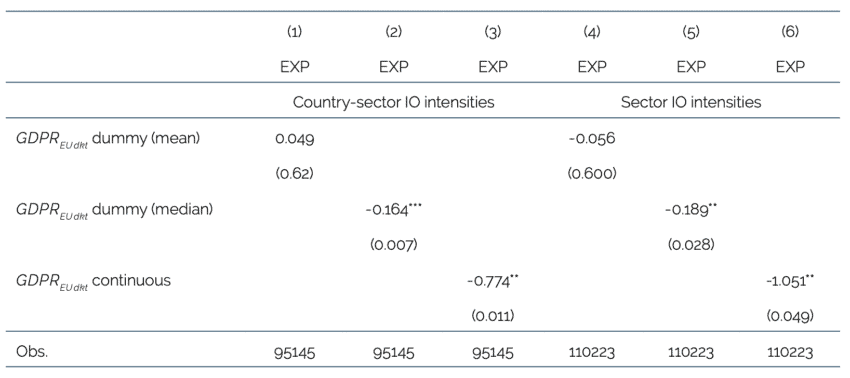

As explained above, the data intensity measure in the GDPREUptk variable is based on firms subscribed to the EU-US DPF agreement, which may render the estimations endogenous given that the agreement was established in recent years. We therefore regress equation (2) with the IO-based intensities instead. The results are presented in Table 4 and Table 5 for imports and exports, respectively.[1] Furthermore, we compute these data intensities using country-industry-specific elasticities of which the results are shown in columns (1)-(3) and industry-specific elasticities, i.e. average across countries. The latter approach tries to control for further endogeneity concerns as country-specific elasticities may result in biased estimates due to selection bias.[2]

Table 4: Baseline results following equation (2) for imports with IO-based intensities Note: * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01. GDPREUdtk is the triple-difference variable, defined as the interaction of 1{t ≥2018} (the GDPR period indicator), the data-intensity variable Ik based on the ICIO input-output (IO) tables, and OTHEUdt, which denotes partner countries with a regulatory regime for cross-border data transfers different from that of the EU. “Dummy” refers to the use of a binary indicator for Ik, while “continuous” refers to the use of sectoral shares. The regressions include origin-sector-time, destination-sector-time, origin-destination-sector, and origin-destination-time fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the origin, destination, and time level.

Note: * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01. GDPREUdtk is the triple-difference variable, defined as the interaction of 1{t ≥2018} (the GDPR period indicator), the data-intensity variable Ik based on the ICIO input-output (IO) tables, and OTHEUdt, which denotes partner countries with a regulatory regime for cross-border data transfers different from that of the EU. “Dummy” refers to the use of a binary indicator for Ik, while “continuous” refers to the use of sectoral shares. The regressions include origin-sector-time, destination-sector-time, origin-destination-sector, and origin-destination-time fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the origin, destination, and time level.

The results in Table 4 show that, for imports, the coefficients are negative and significant across all three specifications when using country-industry-specific elasticities. Under the stricter approach of industry-specific elasticities only, the results remain significant in two out of three specifications. The export results, reported in Table 5, similarly show a negative and significant coefficient result in four out of six specifications.

Table 5: Baseline results following equation (2) for exports with IO-based intensities Note: * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01. GDPREUdtk is the triple-difference variable, defined as the interaction of 1{t ≥2018} (the GDPR period indicator), the data-intensity variable Ik based on the ICIO input-output (IO) tables, and OTHEUdt, which denotes partner countries with a regulatory regime for cross-border data transfers different from that of the EU. “Dummy” refers to the use of a binary indicator for Ik, while “continuous” refers to the use of sectoral shares. The regressions include origin-sector-time, destination-sector-time, origin-destination-sector, and origin-destination-time fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the origin, destination, and time level.

Note: * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01. GDPREUdtk is the triple-difference variable, defined as the interaction of 1{t ≥2018} (the GDPR period indicator), the data-intensity variable Ik based on the ICIO input-output (IO) tables, and OTHEUdt, which denotes partner countries with a regulatory regime for cross-border data transfers different from that of the EU. “Dummy” refers to the use of a binary indicator for Ik, while “continuous” refers to the use of sectoral shares. The regressions include origin-sector-time, destination-sector-time, origin-destination-sector, and origin-destination-time fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the origin, destination, and time level.

4.1 Robustness Check 1: Data Protection Regimes

Many countries’ regulatory frameworks for data address not only cross-border transfers of personal data but also broader data protection measures. These frameworks typically include requirements for obtaining the data subject’s consent, extensive rights such as access, rectification, and deletion of data, and, in most cases, the establishment of dedicated data protection authorities. While such obligations may raise firms’ costs, primarily through compliance, they are also expected to strengthen consumer trust in the digital economy. When a country does not implement such a regime, data subjects have only limited rights when it comes to how their personal data is handled.[3]

As a robustness check, we examine whether the absence of a data protection regime in partner countries similarly produces negative results. The logic is that countries lacking a comprehensive data protection framework are also likely to face higher transaction costs when trading with the EU. While the correlation between countries with substantially different data transfer regimes and those without a data protection regime is around 0.74, the two groups do not fully overlap. Figure A2 shows that, over time, many countries have adopted a data protection framework, but this does not necessarily imply that they follow conditional flow rules for personal data transfers, as required under the EU model

Indirectly, therefore, using information on whether countries have no data protection regime, rather than a different regime for data transfers, in our regressions serves as a falsification test. If the coefficient estimates were also negative and significant, this would suggest that the observed trade impact may not be specifically driven by differences in data transfer regulations, but rather by the construction of an artificial control group.

To test this, we replace the OTHEUdt term in equation (1) with a variable that records whether countries have implemented comprehensive data protection regimes over time, denoted NDPEUdt. This variable is also sourced from the dataset developed by Ferracane and van der Marel (2025).[4] The triple interaction term then becomes:

(3) GDPREUdtk = Ik * NDPEUdt * 1{t ≥2018}

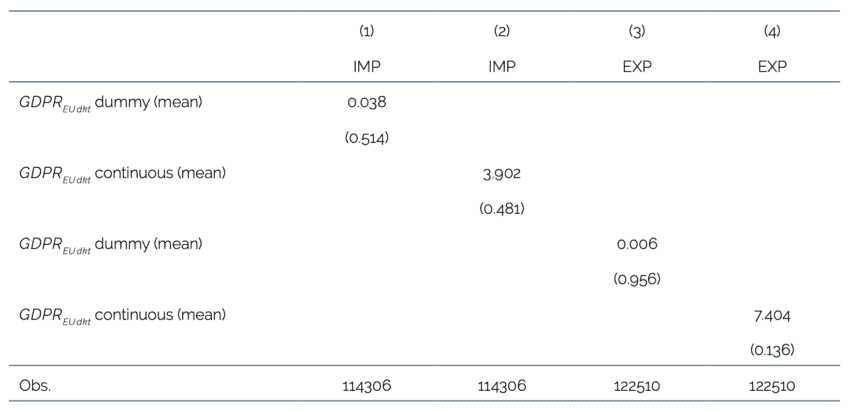

This variable is then used in equation (2) to estimate its impact on both imports and exports. The results, reported in Table 6, use data-intensity measures based on the EU–US DPF agreement computed around the mean. All coefficient estimates are positive but statistically insignificant. Given their lack of significance, these findings confirm that it is specifically regulations related to cross-border personal data transfers, not the mere existence of a comprehensive data protection regime, that matter for understanding the impact on trade.

Table 6: Baseline results following equation (2) for data protection & imports and exports Note: * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01. GDPREUdtk is the triple-difference variable, defined as the interaction of 1{t ≥2018} (the GDPR period indicator), the data-intensity variable Ik based on the EU–US DPF, and NDPEUdt, which denotes partner countries without a comprehensive data protection regime. “Dummy” refers to the use of a binary indicator for Ik, while “continuous” refers to the use of sectoral shares. The regressions include origin-sector-time, destination-sector-time, origin-destination-sector, and origin-destination-time fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the origin, destination, and time level.

Note: * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01. GDPREUdtk is the triple-difference variable, defined as the interaction of 1{t ≥2018} (the GDPR period indicator), the data-intensity variable Ik based on the EU–US DPF, and NDPEUdt, which denotes partner countries without a comprehensive data protection regime. “Dummy” refers to the use of a binary indicator for Ik, while “continuous” refers to the use of sectoral shares. The regressions include origin-sector-time, destination-sector-time, origin-destination-sector, and origin-destination-time fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the origin, destination, and time level.

While some evidence suggests that sector-specific privacy regulations can reduce firms’ ability to use data effectively domestically, for example, in online advertising[5] and in healthcare[6], our results indicate that country-wide data protection regulations do not necessarily have an adverse effect on trade. On the contrary, we find a positive impact, consistent with trust serving as an important channel, although the coefficients remain statistically insignificant.

4.2 Robustness Check 2: Non-Gravity DiD

Our second robustness check employs a triple-difference approach to examine the evolution of trade in digital services following the implementation of the GDPR. This approach, based on trade growth rates, follows Conconi et al. (2018).[7] The standard non-gravity method compares changes in trade for the treated group (i.e., service sectors classified as data-intensive) with changes in the control group (i.e., service sectors classified as non-data-intensive) by estimating the following equation:

(4) ∆IMEU,OTH,k=β1GDPRk+αo+γp+εopk

where ΔIMEU,OTH,k denotes the change in imports for each service sector k of EU members from all countries that applied a different personal data transfer regime between two periods, i.e., before and after 2018 when the GDPR was introduced. To ensure a stable treatment definition, we exclude partner countries that change their data-transfer regime within the estimation window. Including switchers would render treatment status time inconsistent. Although both origin (αo) and partner (γp) fixed effects can be applied to account for EU member- and exporter-level trends in imports, this estimation prevents us from including sector fixed effects and therefore cannot control for any sector-level trends. Excluding this term risks introducing omitted variable bias, since it may be correlated with the GDPRk variable, which is also defined at the sector level.

A triple-difference approach addresses this issue, as ΔIMEU,OTH,k can be reconstructed to capture both cross-sector and cross-country variation in treatment over time. This requires comparing the sector-level growth rates of EU members’ imports from the treated group (i.e., countries with a different data transfer regime) with the sector-level growth rates from the untreated group (i.e., countries with a conditional model). Equation (4) then becomes:

(5) ∆IMEU,OTH,k-∆IMEU,SAF,k=β1 GDPRk+αo+γp+εOTH,SAF,k

in which ΔIMEU,SAF,k measures the change in imports for each service sector k of EU members from all countries that applied a similar personal data transfer regime, classified as a conditional safeguard regime (SAF), between the same two periods. The dependent variable is the difference between the growth rate of EU imports of the service sector from countries with a different data transfer regime and the corresponding growth rate of imports from countries with a regime similar to that of the EU. This specification eliminates the need for sector-level fixed effects, since taking the log change of each service sector within both treated and untreated groups differences out those fixed effects. The assumption behind this approach, however, is that trends in each service sector are the same for imports from both groups of countries.

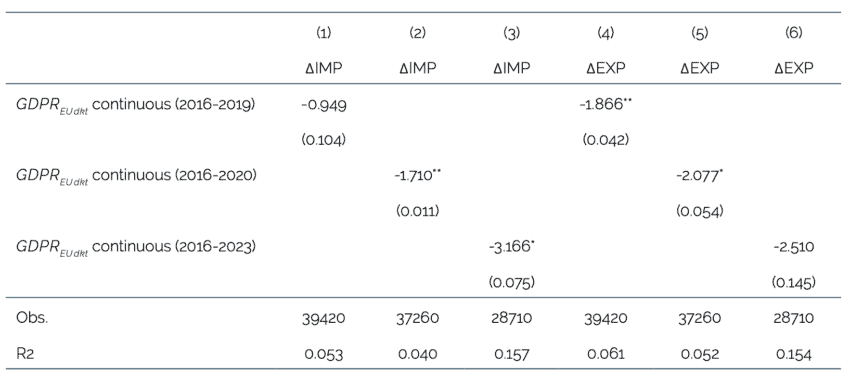

For similar reasons as described above, we regress equation (4) also for exports so that the dependent variable becomes ΔEXEU,OTH,k – ∆EXEU,SAF,k. Due to the potential distortions in trade patterns caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the period over which the log difference (∆) is calculated is defined for three distinct intervals: 2016-2019, 2016-2020, and 2016-2023. These three periods allow for a more robust assessment of whether any significant coefficient estimates have persisted over the short to medium term. It is important to note that, for these triple-difference specifications, balanced trade data from BaTIS are employed instead of reported data, as the latter contain substantial gaps that prevent consistent computation of the dependent variable for each partner country. Such gaps, resulting from unreported trade flows, could otherwise bias the results. Standard errors are clustered at the industry level.

The results are presented in Table 7. Once again, we report the estimates using the data-intensity measures based on the EU-US DPF agreement, computed around the mean. The results for imports, shown in columns (1)-(3), are negative and statistically significant for two out of the three periods with a longer time horizon. In contrast, the results for exports, reported in columns (4)-(6), display an inverse pattern, with the two periods covering a shorter time horizon yielding significant results.

Table 7: Non-gravity triple difference using continuous data-intensity based on DPF Note: * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01. GDPREUdtk is the triple-difference variable, defined as the interaction of 1{t ≥2018} (the GDPR period indicator), the data-intensity variable Ik based on the EU–US DPF. “Continuous” refers to the use of sectoral shares. The regressions include exporter and destination fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the sector level. The dependent variable for imports is ΔIMEU,OTH,k – ∆IMEU,SAF,k referring for each of the three time periods, whereas for exports is ∆EXEU,OTH,k-EX similarly for each time period.

Note: * p<0.10 ** p<0.05 *** p<0.01. GDPREUdtk is the triple-difference variable, defined as the interaction of 1{t ≥2018} (the GDPR period indicator), the data-intensity variable Ik based on the EU–US DPF. “Continuous” refers to the use of sectoral shares. The regressions include exporter and destination fixed effects. Standard errors are clustered at the sector level. The dependent variable for imports is ΔIMEU,OTH,k – ∆IMEU,SAF,k referring for each of the three time periods, whereas for exports is ∆EXEU,OTH,k-EX similarly for each time period.

[1] When using continuous data-intensity measures, no median or mean thresholds are required, as the IO table classification aligns directly with the trade data classification. This does not hold for the dummy variables, where assigning a value of 1 is based on the mean or median threshold.

[2] Generally, industry-specific elasticities are convenient, as they control for arbitrary country- and industry-specific factors related to the dependent variable, thereby making the regressions more exogenous. However, this approach assumes equal industry technologies across countries, which the literature has challenged, as it may introduce measurement error bias (Ciccone and Papaioannou, 2023). Moreover, using country-industry-specific elasticities could also lead to biased estimates, since a country’s economic performance as measured in our dependent variable may influence its sourcing decisions, resulting in upward shift. We therefore report both approaches.

[3] When a comprehensive regime is lacking, it is not uncommon for certain sensitive categories of data, such as in finance and health, to have sectoral rules on data processing. In these cases, data protection is usually treated as a consumer protection right.

[4] Ferracane, M. F., & van Der Marel, E. (2025). Governing personal data and trade in digital services. Review of International Economics, 33(1), 243-264.

[5] Goldfarb, A., & Tucker, C. (2012). Privacy and innovation. Innovation policy and the economy, 12(1), 65-90.

[6] Miller, A. R., & Tucker, C. E. (2011). Can health care information technology save babies?. Journal of Political Economy, 119(2), 289-324.

[7] Conconi, P., García-Santana, M., Puccio, L., & Venturini, R. (2018). From final goods to inputs: the protectionist effect of rules of origin. American Economic Review, 108(8), 2335-2365.

5. Conclusion and Policy Implications

This paper employs a triple-differences methodology to construct an appropriate control group and assess whether trade in digital services between EU member states and third countries has been affected. We apply this approach in both a gravity and a non-gravity framework. The results show that, for both imports and exports, trade in digital services experienced a significant decline following the introduction of the GDPR in 2018.

Several important points emerge from our findings. First, differences in how the EU and partner countries govern cross-border data transfers–rather than differences in domestic data protection regimes–are the main drivers of the negative outcomes we observe. In other words, divergences in data transfer rules under the GDPR, compared with mechanisms used by other countries, lead to a decline in digital services trade for EU member states. From a policy perspective, this suggests that variations in safeguard mechanisms required by the EU, such as Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs) and Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs), raise trade costs and thereby contribute to the observed negative effects.

For instance, under the GDPR, companies relying on Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) are required to ensure that the recipient country can effectively meet the agreed-upon level of data protection. This means firms must assess whether national laws in the destination country conflict with the obligations under the SCCs. As part of this process, companies are obliged to conduct extensive documentation, known as the Transfer Impact Assessment. If the assessment shows that the recipient country falls short in protecting personal data, the European Commission requires additional safeguards to mitigate these risks. As such additional safeguards are not required in countries with compatible regulatory systems, these requirements can make the safeguard mechanisms particularly burdensome for companies.

Second, while the negative outcomes for imports are more intuitive, those for exports require further discussion. EU digital imports that rely on personal data often require the underlying data to be transferred to the partner country, which then exports the services to the EU. Differences in how these data transfers are regulated therefore directly affect the ability of EU member states to import. For exports, however, a more indirect mechanism is likely responsible for the negative results operating through different channels.

One possible explanation is that reduced imports lead to a decline in exports, as technology-intensive firms in EU member states are unable to source the best available service inputs under the GDPR’s safeguard mechanisms, thereby weakening their international competitiveness. Second, burdensome data transfer requirements are likely to make the production of AI services more difficult. AI technologies rely on large volumes of data sourced from around the world, and costly transfer mechanisms may hinder the training, development, and delivery of data-intensive AI services, as well as other data-driven investments such as cloud infrastructure, thereby affecting EU exports. This is particularly significant given that the GDPR applies to all personal data located within the EU, not only that of EU citizens.

Finally, due to the high costs of data transfer mechanisms, firms may adjust their value chains by relocating specific operations outside the EU to better manage risks, costs, and compliance exposure. For example, an EU-based company might store or process personal data locally within the EU to simplify compliance while placing only anonymised or transformed services outside the EU. If complying with the GDPR raises the cost of certain types of data activities or service delivery, firms may shift parts of their value chain (e.g., software engineering or analytics) to lower-cost jurisdictions, not to avoid the GDPR, but to offset compliance expenses. In some cases, companies may even redesign their offerings to minimise the use of personal data altogether (e.g., shifting from individual-level tracking to aggregate-level insights), which can, in turn, shape their international deployment strategies.

Further research is needed to determine which channel exerts the stronger effect, as our analysis cannot address this question with the available data. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that while the GDPR has contributed to harmonising privacy standards across EU member states, additional efforts to align cross-border data transfer mechanisms with those of external partners may be necessary to achieve broader regulatory convergence.

References

Aaronson, S. A., & Leblond, P. (2018). Another digital divide: The rise of data realms and its implications for the WTO. Journal of International Economic Law, 21(2), 245-272.

Anderson, J. E., Borchert, I., Mattoo, A., & Yotov, Y. V. (2018). Dark costs, missing data: Shedding some light on services trade. European Economic Review, 105, 193-214.

Arnold, J., Javorcik, B., & Mattoo, A. (2006). The productivity effects of services liberalization: Evidence from the Czech Republic. World Bank working paper, 1-38.

Arnold, J. M., Javorcik, B., Lipscomb, M., & Mattoo, A. (2016). Services reform and manufacturing performance: Evidence from India. The Economic Journal, 126(590), 1-39.

Barone, G., & Cingano, F. (2011). Service regulation and growth: evidence from OECD countries. The Economic Journal, 121(555), 931-957.

Beverelli, C., Fiorini, M., & Hoekman, B. (2017). Services trade policy and manufacturing productivity: The role of institutions. Journal of International Economics, 104, 166-182.

Bradford, A. (2020). The Brussels effect: How the European Union rules the world. Oxford University Press.

Bradford, A. (2023). Digital empires: The global battle to regulate technology. Oxford University Press.

Brunel, C., & Zylkin, T. (2022). Do cross‐border patents promote trade?. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique, 55(1), 379-418.

Chivot, E., & Cory, N. (2020). Response to European Commission Consultation on Transfers of Personal Data to Third Countries and Cooperation Between Data Protection Authorities. The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, April, 29.

Conconi, P., García-Santana, M., Puccio, L., & Venturini, R. (2018). From final goods to inputs: the protectionist effect of rules of origin. American Economic Review, 108(8), 2335-2365.

Cory, N., Castro, D., & Dick, E. (2020a). ‘Schrems II’: What Invalidating the EU-US Privacy Shield Means for Transatlantic Trade and Innovation. Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

Cory, N., Dick, E., & Castro, D. (2020b). The role and value of standard contractual clauses in EU-US digital trade. Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

Cusolito, A., van der Marel, E., Nayyar, G., & Pleninger, R. (2025). Data flows restrictiveness and (un)equal productivity and jobs effects. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. Forthcoming.

Demirer, M., Hernández, D. J. J., Li, D., & Peng, S. (2024). Data, privacy laws and firm production: Evidence from the GDPR (No. w32146). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Egger, P. H., & Tarlea, F. (2015). Multi-way clustering estimation of standard errors in gravity models. Economics Letters, 134, 144-147.

Ferracane, M. F., Kren, J., & Van Der Marel, E. (2020). Do data policy restrictions impact the productivity performance of firms and industries?. Review of International Economics, 28(3), 676-722.

Ferracane, M. F., & van Der Marel, E. (2025). Governing personal data and trade in digital services. Review of International Economics, 33(1), 243-264.

Ferracane, M. B., Hoekman, B., Santi, F., & van der Marel, E. (2025). Digital trade, data protection and the EU adequacy club. Economica. Forthcoming.

French, S. (2017). Comparative advantage and biased gravity. UNSW Business School Research Paper, (2017-03).

French, S., & Zylkin, T. (2024). The effects of free trade agreements on product-level trade. European Economic Review, 162, 104673.

Frey, C. B., & Presidente, G. (2024). Privacy regulation and firm performance: Estimating the GDPR effect globally. Economic Inquiry, 62(3), 1074-1089.

Gao, H. (2018). Digital or trade? The contrasting approaches of China and US to digital trade. Journal of International Economic Law, 21(2), 297-321.

Goldberg, S. G., Johnson, G. A., & Shriver, S. K. (2024). Regulating privacy online: An economic evaluation of the GDPR. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 16(1), 325-358.

Goldfarb, A., & Tucker, C. (2012). Privacy and innovation. Innovation policy and the economy, 12(1), 65-90.

Goldfarb, A., & Trefler, D. (2018). AI and international trade (No. w24254). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Head, K., & Mayer, T. (2014). Gravity equations: Workhorse, toolkit, and cookbook. In Handbook of international economics (Vol. 4, pp. 131-195). Elsevier.

Jia, J., Jin, G. Z., & Wagman, L. (2021). The Short-Run Effects of the General Data Protection Regulation on Technology Venture Investment. Marketing Science, 40(4), 661-684.

Jia, J., Jin, G. Z., Leccese, M., & Wagman, L. (2025). How Does Privacy Regulation Affect Transatlantic Venture Investment? Evidence from GDPR (No. w33909). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Johnson, G. (2022). Economic research on privacy regulation: Lessons from the GDPR and beyond (NBER Working Paper No. 30705). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Miller, A. R., & Tucker, C. E. (2011). Can health care information technology save babies?. Journal of Political Economy, 119(2), 289-324.

Silva, J. S., & Tenreyro, S. (2006). The log of gravity. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 641-658.

Silva, J. S., & Tenreyro, S. (2011). Further simulation evidence on the performance of the Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood estimator. Economics Letters, 112(2), 220-222.

Sun, R., & Trefler, D. (2023). The impact of AI and cross-border data regulation on international trade in digital services: A large language model (No. w31925). National Bureau of Economic Research.

van der Marel, E. (2016). Ricardo does services: Service sector regulation and comparative advantage in goods. In Research handbook on trade in services (pp. 85-106). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Van der Marel, E., & Ferracane, M. F. (2021). Do data policy restrictions inhibit trade in services?. Review of World Economics, 157(4), 727-776.

World Bank. (2021). World development report 2021: Data for better lives. World Bank.