Global Digital Trade Takes Off: Is EU Digital Policy Keeping Pace?

Published By: Elena Sisto Erik van der Marel

Research Areas: Data, AI, and Emerging Technologies EU Single Market, Institutions, and Governance Industrial and Competitiveness Policy

Summary

Global digital trade is increasingly shifting toward faster-growing regions outside Europe, driving greater external demand for the EU’s digitally deliverable services. As digital supply chains continue to mature, they present additional opportunities for the EU to expand and strengthen its digital trade.

However, recent evidence suggests that the EU’s regulatory environment may be limiting its potential gains. Since its introduction in 2018, the GDPR’s cross-border data transfer rules are estimated to have reduced the EU’s digital services trade, including exports, by up to 10–12 percent.

To enhance its digital trade performance, the EU has several paths forward. First, Brussels should revise the GDPR’s cross-border safeguards while retaining provisions where data protection has a positive but limited impact on trade. Evidence indicates that the former constraints are hindering digital trade potential, whereas the latter are not.

Second, the EU should expand its adequacy framework to include more trading partners, a step that could further increase digital services trade by up to 9 percent, with additional gains across the network of adequacy-recognised countries when the United States is included.

Additionally, as the AI Act intersects with the GDPR, companies that use personal data in AI systems face dual compliance burdens. This highlights the need for a parallel adequacy framework for AI to enhance regulatory coherence and support AI- and data-related trade.

Finally, the EU should broaden its Digital Partnership Agreements. Even non-binding cooperation on data, AI, competition, and standards within preferential trade agreements can increase AI-related trade by up to 9 percent, strengthening both digital innovation and competitiveness.

This policy brief is based on three recent studies that have been published:

- Sisto, E. and E. van der Marel (2025) “Privacy at a Price? An Empirical Analysis of GDPR’s Impact on EU Trade Flows”, ECIPE Occasional Paper No. 11/2025, ECIPE, Brussels.

- Sisto, E. and E. van der Marel (2025) “The Trade Effects of AI Provisions in PTAs: Does Non-binding matter?”, ECIPE Occasional Paper No. 12/2025, ECIPE, Brussels.

- Ferracane, M, B Hoekman, E van der Marel and F Santi (2025) “Digital Trade, Data Protection and the EU Adequacy Club”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 19882. CEPR Press, Paris & London, forthcoming in Economica.

1. Two Global Forces Reshaping Europe’s Digital Future

Two global trends are set to shape the EU’s future position in digital trade.

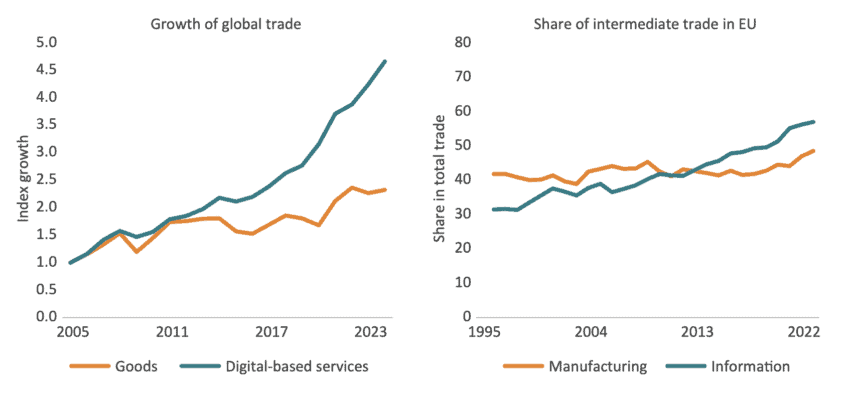

First, the exchange of digital and digitally enabled services is accelerating rapidly, outpacing the growth of any manufacturing sector, a pattern that has held since 2005 (Figure 1, right). The European Commission projects that around 90 percent of demand for European goods and services will originate outside the EU, which is likely to extend to digital services as well.[1] Between 2015 and 2024, Asia (22.6 percent) and the Middle East (18.7 percent) contributed more to global digital services trade growth than Europe (18.3 percent), pointing to a gradual shift in the digital economy’s centre of gravity toward faster-growing regions beyond Europe’s borders.

Second, digital services industries are maturing. Over the past decade, they have grown at remarkable speed, with levels of capital investment now on par with many manufacturing sectors. The old notion that digital services merely support manufacturing supply chains is increasingly outdated. They have become system industries that lead in global investments and influence who participates in the digital supply chain. Multinationals such as Google or SAP now drive complex global ecosystems in their own right. In the EU, trade in intermediate digital goods and services has already outpaced many traditional intermediate goods, reflecting a structural move toward deeply interconnected digital value chains (Figure 1, right).

Figure 1: Global trade and EU’s share intermediate products in total gross exports Source: Authors using WTO DDS database, UNCTAD, and TiVA. Note: Growth of global trade measures normalised trend set at 1 in 2005 for both goods and digitally deliverable services (left panel). Share of intermediate trade is based on total trade of both final and intermediate trade. Information industries refer to digital services such as telecom, information, and software services, as well as digital goods.

Source: Authors using WTO DDS database, UNCTAD, and TiVA. Note: Growth of global trade measures normalised trend set at 1 in 2005 for both goods and digitally deliverable services (left panel). Share of intermediate trade is based on total trade of both final and intermediate trade. Information industries refer to digital services such as telecom, information, and software services, as well as digital goods.

Taken together, these trends could play to Europe’s strengths. The EU economy is heavily weighted toward services that are easily delivered across borders, including consultancy, R&D, market research, accountancy, finance, insurance, telecoms, and data processing. European firms such as Ericsson, Accenture and SAP already hold strong positions in global markets and are well placed to expand as external demand accelerates–in some cases faster than in Europe itself. The rapid rise of cloud computing, artificial intelligence and quantum technologies is likely to deepen these opportunities further, reinforcing Europe’s competitive edge in high-value, digitally deliverable services.

[1] SME internationalisation beyond the EU – Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs

2. When Regulation Meets Trade

However, the EU’s ability to turn these opportunities into real trade gains will depend as much on its own digital policies as on global market dynamics.

In recent years, Brussels has rolled out a wave of digital regulations–most notably the GDPR, the AI Act and the Digital Markets Act (DMA)–many of which carry extraterritorial reach. This means that if, for example, an AI system is developed abroad but its services are offered in the EU and affect European consumers, the foreign provider must comply with EU rules. While these regulations often address non-economic concerns, such as protecting data privacy through the GDPR or preserving democratic control over digital platforms through the DMA, they also risk raising compliance costs and creating frictions that could blunt Europe’s competitive edge in global digital markets.[1]

Take the GDPR. Introduced in 2018, the regulation set clear rules for how both European and foreign companies offering digitally enabled services handle and process the personal data of EU citizens. These rules fall broadly into two categories. The first relates the transfer of personal data from firms inside the EU to those outside its borders, requiring companies to use legal instruments such as Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) or Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs), often through detailed and burdensome compliance templates. The second involves data protection obligations within companies themselves, including appointing data protection officers, conducting impact assessments whenever data moves abroad, and implementing privacy safeguards.

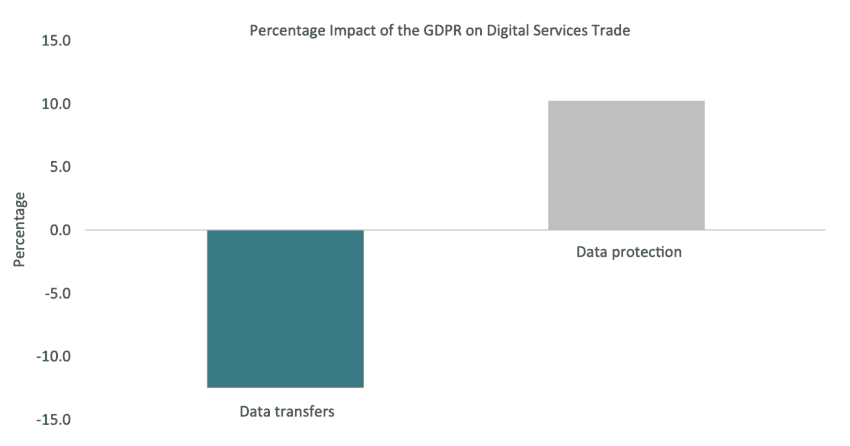

Combined, these GDPR rules have not only extended the EU’s regulatory reach well beyond its borders but have also increased the cost of trading with partner countries. Since its introduction in 2018, the GDPR’s regulations on cross-border data transfers is estimated to have reduced the EU’s digital services imports by around 10-12 percent (Figure 2).[2] In practical terms, due to the GDPR European firms are less inclined to outsource service activities that rely on personal data from EU citizens, deterred by the complex legal instruments required for compliance. This deprives companies of access to innovative technologies embedded in foreign services–precisely the kind of tools needed to keep EU companies competitive in global markets.

For its part, the EU frames its digital regulations not simply as safeguards but as an economic asset. By creating legal certainty through clear and predictable standards, Brussels argues, these rules will over time help generate global demand for European digital products and services. Additionally, by setting standards early and leveraging the size of its market, the EU encourages foreign firms to align with its rules–a dynamic often referred to as the ‘Brussels Effect’ and already evident with the GDPR. More than 60 percent of countries worldwide have adopted EU-style frameworks for data transfers and processing.[3] This gives firms already in compliance–mainly European ones–a competitive edge, further strengthening the EU’s position in global digital markets and supporting its export ambitions.

Figure 2: Impact of GDPR rules on digital services trade (imports and exports) Source: Authors using Sisto and van der Marel (2025). Note: an average of the estimated coefficients is taken to calculate the overall impact of the GDPR on digital services trade for both imports and exports. The GDPR framework is divided into data transfer rules and data protection rules. The negative impact of data transfer rules is significant, while the positive impact of data protection rules is not statistically significant and is therefore marked in grey.

Source: Authors using Sisto and van der Marel (2025). Note: an average of the estimated coefficients is taken to calculate the overall impact of the GDPR on digital services trade for both imports and exports. The GDPR framework is divided into data transfer rules and data protection rules. The negative impact of data transfer rules is significant, while the positive impact of data protection rules is not statistically significant and is therefore marked in grey.

[1] Frey, C.B. and G. Presidente (2024) “Privacy Regulation and Firm Performance: Estimating the GDPR Effect Globally,” Economic Inquiry, Vol. 62, No. 3, pages 1074-1089.

[2] Sisto, E. and E. van der Marel (2025) “Privacy at a Price? An Empirical Analysis of GDPR’s Impact on EU Trade Flows”, ECIPE Occasional Paper No. 11/2025, ECIPE, Brussels.

[3] Ferracane, M. and E. van der Marel (2025) “Governing Personal Data and Trade in Digital Services”, Review of International Economics, Vol. 33, No. 1, pages 243-264.

3. When Rules Collide with Exports

In practice, while European policymakers aimed to build trust among businesses and users, the outcome has been the opposite in trade terms: digital exports have fallen rather than grown. Further evidence finds that, in addition to curbing imports, GDPR rules have reduced export opportunities for EU companies between 4-10 percent. By limiting firms’ ability to access the best available digital service inputs in the value chain, the GDPR is directly weakening the international competitiveness of the EU’s digital firms that rely on them.

These constraints also spill over into production. GDPR rules make it harder to develop and scale digital technologies within the EU. AI systems, for instance, depend on large volumes of data sourced globally, and costly transfer mechanisms can slow down the training, development, and delivery of data-intensive services.[1] This also affects other data-driven investments, such as cloud infrastructure, with knock-on effects for exports. The impact is amplified by the fact that the GDPR covers all personal data located in the EU–not just that of EU citizens–making compliance even more complex for firms in fast-moving digital sectors.

Faced with mounting costs and regulatory complexity, many firms are likely to have restructured their value chains to remain competitive. Some may have shifted specific operations outside the EU to manage compliance more efficiently. For example, by keeping personal data within the EU but processing anonymised data abroad. Others are likely to have relocated entire functions such as software engineering or analytics to lower-cost jurisdictions to offset compliance costs. In some cases, companies may have even redesigned their products to reduce reliance on personal data, reshaping their international strategies in the process.

These pressures are now set to deepen. With parts of the AI Act already in force, firms face a second layer of regulation that directly interacts with the GDPR. The AI Act explicitly refers to data protection rules–most notably in Article 10 (data governance) and Article 52 (transparency)–meaning companies using personal data in AI systems must comply with both frameworks simultaneously. For exporters of digital services, this results in stacked compliance obligations, higher legal risks and rising operational costs, further narrowing Europe’s ability to scale and export its digital and digitally deliverable services.

While Brussels sees these regulations to build trust and set global standards, their combined weight risks trading short-term compliance cost for long-term regulatory ambition–a strategic bet that may come at a high cost for Europe’s digital trade competitiveness.

[1] Klügl, F. and H.K. Nordås (2025) “Cross-border Data Flows and AI Adoption: Agent-based Model Simulations”, Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, Vol. 75, pages 676-688.

4. Reducing Trade Cost of Digital Rules

To reconcile trust-based regulation with trade openness, the EU can pursue targeted measures to improve regulatory coherence and strengthen firms’ ability to operate across borders.

First, with a review already planned for next year, the EU should revisit the GDPR in a more nuanced way. Evidence discussed above also shows that the GDPR regulation’s adverse effects are primarily linked to safeguard measures governing cross-border data transfers, not to data protection rules themselves. In fact, the latter appears to have a positive, albeit statistically insignificant, effect on the EU’s digital services trade, likely by fostering trust in Europe’s digital ecosystem. The takeaway is clear: current mechanisms for cross-border data transfers should be eased or made more operational, ideally through more streamlined and predictable international arrangements. This is particularly important for countries with different regulatory systems for data, which account for around 52 percent of Europe’s digital services trade. Key partners in this group include the United States, China, Vietnam, and Türkiye.

Second, the EU should expand its adequacy arrangements. At present, only 15 countries have received a unilateral decision from Brussels confirming that their privacy regimes provide protection equivalent to the EU’s. This designation allows for the free flow of personal data between the EU and these partner countries, eliminating the need for additional safeguard measures. Research shows that such adequacy decisions significantly boost digital services trade between the EU and the countries concerned.[1] Priority should be given to major partners whose privacy systems increasingly mirror the EU’s.[2] When relevant the EU should offer them the option to operate under EU regulatory supervision, providing legal capacity. This is especially relevant for accession countries to foster deeper integration into the EU digital market in advance.[3] Moreover, a network effect emerges among adequacy-granted countries themselves, amplifying the overall trade impact. This effect becomes particularly visible when the United States is included in the framework, currently through the EU–U.S. Data Privacy Framework (DPF), previously referred to as the Data Framework Agreement.

Together, these effects suggest that adequacy arrangements can serve as a powerful tool to strengthen Europe’s digital competitiveness. The policy implication is straightforward: extend adequacy decisions and facilitate the smooth operation of onward data transfers, particularly when the United States is part of the network. Moreover, given that AI systems depend heavily on the availability and seamless movement of data across borders, and that GDPR rules are directly linked to the AI Act, it would be logical to develop a parallel adequacy framework for AI models. Such an approach could help ensure regulatory coherence while supporting innovation and strengthening digital trade and technology ties with the EU’s key partners.

Finally, Brussels should make the most of its bilateral trade arrangements in the digital field. The EU currently has several preferential trade agreements (PTAs) with deep and binding commitments on digital trade. Some of these include data-related provisions, such as the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement and the EU-Chile Advanced Framework Agreement (the latter not yet in force). Although these agreements aim to modernise digital trade rules, they do not always address deeper data-related measures or include advanced AI-related provisions. This is understandable, given the EU’s reluctance to commit to legally binding rules that could overlap or conflict with the GDPR and the AI Act.

The EU’s Digital Partnership Agreements (DPAs) offer a promising middle ground. Although often criticised for their lack of legally enforceable obligations, they focus on regulatory dialogue and alignment, standard-setting, and facilitating interoperability between digital markets. Notably, these non-binding digital agreements, along with similar non-binding provisions in PTAs, can still generate significant trade gains.[4] This is especially true in areas related to data flows, where developing mechanisms to address regulatory barriers, as well as cooperation on AI, digital competition, and interoperable standards, can make a difference. Regulatory cooperation in these emerging areas is not just symbolic; it can deliver real economic returns, with potential trade gains of up to 9 percent, research finds.

[1] Ferracane, M, B Hoekman, E van der Marel and F Santi (2025) “Digital Trade, Data Protection and the EU Adequacy Club”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 19882. CEPR Press, Paris & London, forthcoming in Economica.

[2] Potential candidates such as Australia (post-Privacy Act reforms), Chile (Law 21.719), and the EU’s Eastern Partnership frontrunners (Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine), could be considered only once reforms are fully implemented and an enforcement and redress track record is established.

[3] Erixon, F., Lamprecht, P., van der Marel, E., Sisto, E., & Zilli, R. (2024). “The Extraterritorial Impact of EU Digital Regulations: How Can the EU Minimise Adverse Effects for the Neighbourhood?” Bertelsmann Stiftung.

[4] Sisto, E. and E. van der Marel (2025) “The Trade Effects of AI Provisions in PTAs: Does Non-binding matter?”, ECIPE Occasional Paper No. 12/2025, ECIPE, Brussels.

5. Conclusion

The EU’s digital future will be determined as much by the rules it sets for itself as by the global markets in which its firms compete. As the centre of gravity in the digital economy shifts toward faster-growing regions beyond Europe’s borders, Brussels will need to ensure that its regulatory framework is not only trusted at home but also compatible with the rest of the world. As Draghi’s report makes clear, Europe must move beyond fragmented and overly rigid regulatory structures if it wants to remain competitive in a fast-changing digital landscape. Evidence already shows that GDPR data transfer rules have constrained export potential, and additional regulatory layers introduced through the AI Act risk amplifying these pressures.

Yet the tools to fix this are already within reach. If Europe wants to lead in digital trade–not just regulate it–it must modernise its rules to reflect economic realities. Expanding adequacy decisions, streamlining transfer mechanisms, and integrating data and AI cooperation into digital partnerships can help reduce trade frictions without weakening trust. Additionally, aligning GDPR reform with the implementation of the AI Act would mark a decisive shift from defensive regulation to strategic openness. Europe’s next competitive advantage will not come from writing more rules, but from connecting them. In doing so, the EU can turn its regulatory power from a constraint into a genuine competitive asset.