Openness and Fragmentation in EU Defence Procurement

Published By: Lucian Cernat Oscar Guinea Guest Author

Research Areas: EU Single Market, Institutions, and Governance Industrial and Competitiveness Policy Trade, Globalisation and Security

Summary

Europe’s fragmented defence procurement markets undermine Europe’s security efforts. Larger procurement markets, by contrast, deliver sharper competition, lower prices, and stronger incentives for specialisation and technological progress. Using data from the EU’s Tender Electronic Daily (TED), this Policy Brief shows domestic bias in defence procurement: three-quarters of contracts go to national firms, and cross-border awards remain limited outside smaller member states. Two policy steps stand out. First, start small: open competition in non-sensitive products can deliver quick wins. Second, improve data: only around 10 percent of defence spending is captured in TED, far less than total procurement volumes. Better data would allow policymakers to track progress, close information gaps, and take better decisions.

Author presentation: Hannah Preuss is a Young Professional of the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development/GIZ, former trainee at DG TRADE and Economic Security, European Commission. Disclaimer: the views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not represent an official position of the European Commission or BMZ/GIZ.

Lucian Cernat* Disclaimer: the views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not represent an official position of the European Commission.

1. Introduction: The Importance of a Well-Functioning EU Defence Procurement Market

Europe faces its biggest security threat since the Second World War. Meeting it requires a strong European defence ecosystem, rather than a set of fragmented national defence systems. Procurement is central to that effort. The economic case for an EU-wide defence procurement market has long been clear. Contestable markets drive down prices and prevent firms from relying on being the only option or preferential relationships. Competition not only lowers prices but also compels companies to raise their games – investing in better equipment, streamlining processes and pursuing innovations they might otherwise ignore. Larger procurement markets also bring economies of scale and specialisation. This allows firms to focus on particular products or technologies while spreading fixed costs such as research and development across a wider customer base.

Nonetheless, defence contracting in the EU still takes place mostly at the national level, with governments awarding the bulk of contracts to domestic suppliers and channelling around 80 percent of spending through national systems.[1] This longstanding fragmentation produces the opposite of the benefits of scale. Siloed procurement markets push up costs, reduce specialisation and keep European defence firms smaller. When each country orders only 50 or 100 units of a system, rather than pooling demand for several hundred, the unit cost of tanks, ships or aircraft is far higher than it would be in a larger market.[2] For instance, the EU operates more than 170 major weapons systems, against just 30 in the United States, undermining scale, specialisation and innovation.[3]

This Policy Brief uses the publicly available data from the EU TED portal to examine how open EU defence procurement markets are for cross-border competition. We argue that Europe’s security depends not only on bigger national defence budgets, but also on making tenders genuinely contestable, open to the best suppliers across the Union. To inform this debate, Chapter 2 introduces briefly the key EU initiatives in this area. Chapter 3 analyses EU defence procurement using data from the Tender Electronic Daily (TED) database. It sets out member states’ participation in TED and the extent of cross-border competition among EU bidders. The final chapter offers two policy recommendations to deepen EU defence procurement and sharpen the quality of analysis.

[1] Napolitano, A., & Wagemans, D. (2025). Europe’s Defence Crisis: Why More Spending Alone Will Not Keep the Continent Safe.Social Europe. https://www.socialeurope.eu/europes-defence-crisis-why-more-spending-alone-will-not-keep-the-continent-safe.

[2] Mejino-López, J., & Wolff, G. (2024). A European defence industrial strategy in a hostile world. Bruegel Policy Brief 29-2024. https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/european-defence-industrial-strategy-hostile-world.

[3] European Commission. (May 2025). The economic impact of higher defence spending.https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/economic-forecast-and-surveys/economic-forecasts/spring-2025-economic-forecast-moderate-growth-amid-global-economic-uncertainty/economic-impact-higher-defence-spending_en.

2. EU Defence Procurement: A Brief Summary of Key Initiatives

Defence procurement is the process by which governments acquire military equipment, services and technology. Unlike civilian contracts, it is governed by stricter rules to protect national security. This principle is embedded in the EU’s legal framework, notably the Defence and Sensitive Security Procurement Directive (2009/81/EC), which sets common rules for defence and security contracts across the EU.[1] The Directive is designed to promote competition, transparency and fair treatment in awarding contracts, while allowing exemptions where national security demands it.[2] However, government-to-government sales of defence equipment fall outside the Directive.[3]

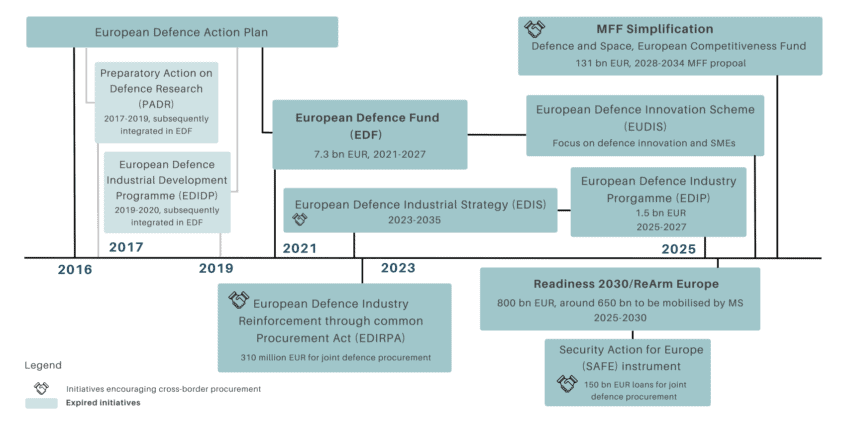

The EU is betting on procurement policy as a tool to achieve its security objectives by playing a dual role. Figure 1 shows the timeline of European defence procurement policies since 2016 and the key initiatives introduced during this period. First, as a buyer, it is deploying its own funds to boost defence spending across the bloc. For example, in spring 2025, President von der Leyen launched the Readiness 2030 package, aiming to mobilise €800 billion by 2030. Of this, €650 billion is to come from member states, with the remaining €150 billion offered by the European Commission as loans. Member states that procure equipment jointly will qualify for preferential loan terms.[4]

Figure 1: Timeline of EU defence procurement initiatives Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

Second, as a market, the EU is pursuing policies such as joint procurement to ensure efficiency gains and a pan-European perspective. Joint defence procurement is intended to tackle poor interoperability and curb home bias in national contracts. In 2023, the EU adopted the European Defence Industry Reinforcement through Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA), offering €310 million to members that buy defence goods jointly.[5] In the same year, the European Commission unveiled the European Defence Industry Strategy (EDIS), setting a target for 40 percent of defence procurement to be joint by 2030.[6] An ambitious goal above the 35 percent joint defence procurement benchmark set by the European Defence Agency in 2007 which has not been achieve yet.[7] In 2022, only 18 percent of defence equipment spending was collaborative.[8] Another recent initiative encouraging joint EU procurement is the SAFE (Security Action for Europe) instrument. Under the SAFE instrument member states can access loans backed by the EU budget (overall 150 bn Euro), if at least two member states (including EFTA/EEA countries and Ukraine) procure defence equipment jointly.

The direction of future EU policy is firmly anchored in the goal of scaling up the defence procurement market: combining the EU’s role as a buyer, incentives for joint procurement, and legislation to deepen and broaden the market.[9] As illustrated at the end of the timeline presented in Figure 1, under the new Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), the European Commission proposed a defence and space funding allocation, merging earlier programmes into the European Competitiveness Fund, which will assign €131 billion to defence and space. In addition, the MFF will boost collaborative procurement through Defence Projects of Common European Interest. [10] The ‘Military Schengen’ proposal, outlined in the Commission’s Military Mobility Package,[11] marks a positive step towards the expansion of the EU defence procurement market. By facilitating cross-border movement of military equipment, it paves the way for more efficient joint procurement.

[1] Article 346 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union allows member states to opt out of EU rules on national security grounds.

[2] The European Court of Justice has also helped interpret these rules, seeking to balance EU internal market principles with member states’ security interests. See: Howorth, J. (2014). Security and Defence Policy in the European Union (2nd ed.). (The European Union Series). Palgrave Macmillan.

[3] see Art. 13(f).

[4] European Commission. (March 2025). Questions and answers on ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_25_790.

[5] European Commission. (November 2024) EU boosts defence readiness with first ever financial support for common defence procurement. https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/eu-boosts-defence-readiness-first-ever-financial-support-common-defence-procurement-2024-11-14_en.

[6] European Commission. (March 2024). A new European Defence Industrial Strategy: Achieving EU readiness through a responsive and resilient European Defence Industry. https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/document/download/643c4a00-0da9-4768-83cd-a5628f5c3063_en?filename=EDIS%20Joint%20Communication.pdf.

[7] European Defence Agency. (2007). Defence Data 2007. https://eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/documents/defence-data/defence-data-2007.pdf.

European Defence Agency. (2025). Defence Data 2024-2025. https://eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/brochures/2025-eda_defencedata_web.pdf.

[8] Draghi, M., & Letta, E. (2024). The future of European competitiveness. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en.

[9] European Commission. (June 2025). Speech by President von der Leyen at the opening session of the NATO Summit Defence Industry Forum. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_25_1606.

[10] European Commission. (July 2025). Europe’s Budget – Defence. https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/e2aa6ac7-9920-4ec6-97fe-399dd5561e54_en?filename=MFF_Defence_16.07.pdf.

[11] European Commission (November 2025). Commission moves towards ‘Military Schengen’ and transformation of defence industry. https://transport.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/commission-moves-towards-military-schengen-and-transformation-defence-industry-2025-11-19_en

3. EU Defence Procurement: A Detailed Assessment Based on the EU TED Portal

The EU’s TED is a valuable source to understand how far defence procurement takes place on a European scale. It is the Union’s official portal for public procurement, tenders above specific contract values must be published in the Supplement to the Official Journal of the European Union and will be accessible through TED.[1] Each year, TED publishes more than 800,000 procurement notices, together worth over €815 billion.[2]

The TED database is freely available as open data. TED contains a key field – “main activity” – which records the core function of the contracting authority. This field categorises authorities by activity, one of which is defence. This allowed us to extract all contracts awarded by authorities declaring defence as their main activity. In 2023, TED contained more than 18,000 defence-related tenders from over 600 contracting authorities. These ranged from national defence ministries and regional branches to individual military bases and units.

Analysing defence procurement through the TED database has two main shortcomings. First, the value of defence contracts recorded in TED is far smaller than the total defence spending by EU countries. Second, the TED sample is not random: it over-represents some types of defence goods and services, while under-representing others.

As noted previously, defence procurement is subject to special rules that allow contracting authorities to exempt certain tenders from publication and open competition when they invoke national security. In addition, the Defence Procurement Directive does not cover government-to-government (G2G) sales. This matters because G2G deals make up a significant share of EU defence procurement. For instance, between 2005 and 2012, intra-EU G2G purchases accounted for about 9 percent of total spending on defence equipment.[3] A recent paper by Wolff and Mejino-López analysed European G2G purchases from the United States through the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) programme. They found that between 2022 and 2024, European countries sourced around half of their military equipment from the US and spent $76 billion on American weaponry in 2024.[4]

In 2023, defence-related procurement contracts published in TED were worth more than €30 billion. To put this in perspective, the European Defence Agency estimated total EU defence spending at about €280 billion.[5] This means that only around 10 percent of EU defence procurement runs through TED. A similar pattern emerges when comparing TED data with research by the Kiel Institute.[6] For 2023, the Kiel Institute estimated German defence orders at about €42 billion, compared with roughly €4 billion recorded in TED.

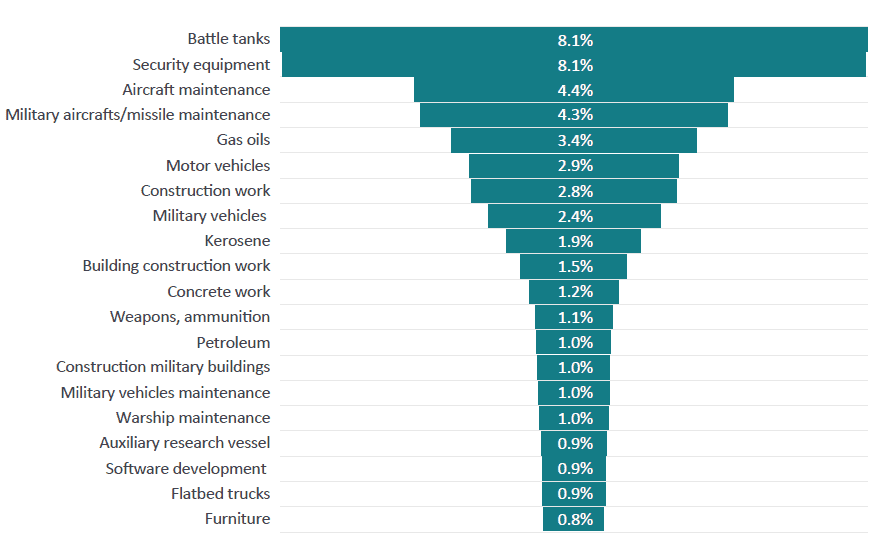

The second shortcoming relates to potential biases within the TED database’s coverage of defence procurement products. It is reasonable to assume that spending on strategic, high-end military equipment lies largely outside TED. This suggests that defence procurement recorded in TED mostly concerns less sensitive items, and is therefore more market-driven and competitive. Figure 2 shows the top 20 defence products procured via TED.[7] It reveals that the vast majority of the spending is made on maintenance, services, construction or consumables. The TED data also contains contracts for heavy military equipment: the single largest item is battle tanks, making up more than 8 percent of TED-recorded defence spending. However, other major hardware items such as fighter jets, missiles, helicopters or submarines remain absent from the list.

Figure 2: EU defence procurement by product (TED data, 2023)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the TED database.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the TED database.

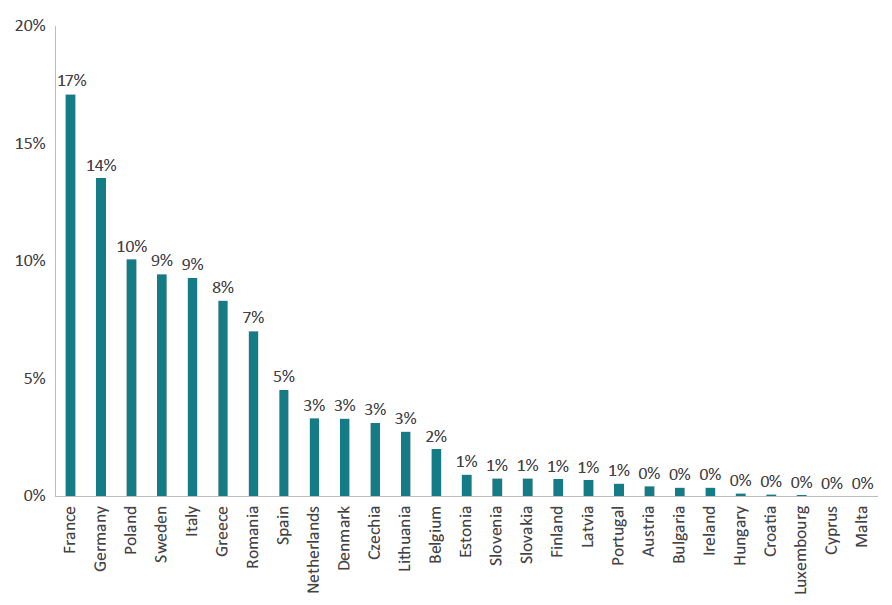

Despite these caveats, which prevent broad generalisations about the entire EU defence procurement market, the TED data still yields useful policy insights. First, the breakdown by member state is revealing. Defence procurement recorded in TED broadly mirrors each country’s share of overall defence spending.[8] Figure 3 shows that the top four EU countries (France, Germany, Poland and Sweden) make up about half of all TED-recorded defence spending. Some, such as Sweden, Greece and Romania, use TED more than their share of overall EU defence spending would suggest. Others, such as Germany, the Netherlands and Italy, show a smaller share on TED than their weight in EU defence spending.

Figure 3: EU defence procurement by member state (TED data, 2023)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the TED database.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the TED database.

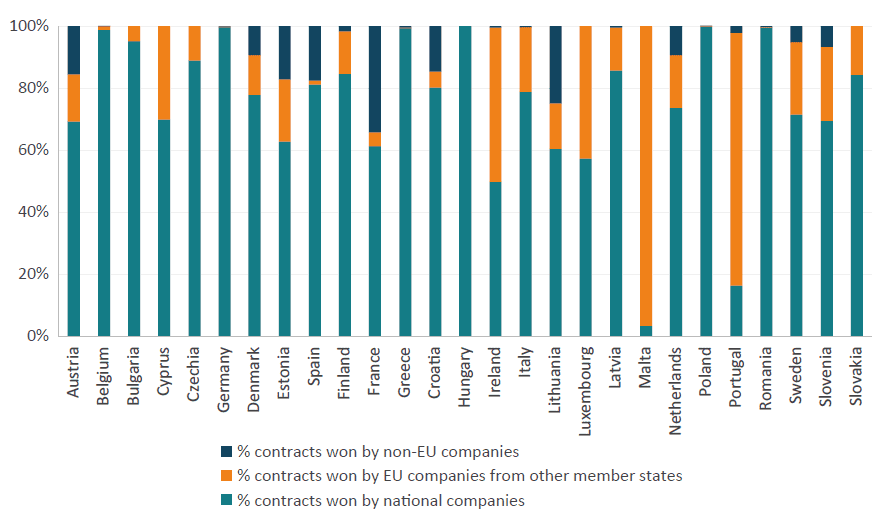

Another critical insight from the TED database concerns the level of cross-border competition in EU defence procurement. This can be analysed by breaking down contracts according to the nationality of the winning bidder. Figure 4 shows the share of contracts won by domestic firms, firms from other EU member states, and non-EU competitors.[9]

The first clear finding from the TED data is that three-quarters of defence contracts across the EU were awarded to domestic firms. For example, nearly all contracts published on TED in 2023 by Germany, Poland, Belgium, Hungary, Greece and Romania went to domestic suppliers. Other countries, including Bulgaria, Czechia and Slovakia, also show a heavily domestic award structure. Figure 4 also shows the extent of cross-border competition within EU defence procurement. On average, 19 percent of contracts were awarded to firms from another EU member state. Countries with smaller domestic markets tend to award a larger share of their TED defence contracts to firms from other EU states: Malta (97 percent), Portugal (82 percent), Ireland (50 percent), Luxembourg (43 percent) and Cyprus (30 percent). The ‘buy national’ conclusion was also confirmed by Wolff and Mejino-López.[10]

The rules governing EU defence procurement also make possible for non-EU firms to take part in certain tenders. The Defence and Sensitive Security Procurement Directive allows firms from third countries to bid for EU contracts if their countries are member of the WTO’s Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) or have signed a Free Trade Agreement with the EU that includes procurement commitments. TED data show that foreign participation remains limited, at just 6 percent, with 14 EU countries recording no contracts awarded to non-EU companies. The limited success rate of non-EU firms can also be explained by their low participation rate: only 0.1 percent of all bids in TED defence procurement came from non-EU firms. There were some exceptions: France (34 percent), Lithuania (25 percent), Spain (18 percent), Estonia (17 percent) and Austria (16 percent) awarded a notable share of contracts to non-EU suppliers. It is also worth noting that other sources[11] indicate that a substantial share of EU defence spending goes to non-EU suppliers, particularly from the United States. The small share of non-EU winners in TED suggests that much of this spending took place via other defence procurement instruments that were not published in TED.

Figure 4: Contracts awarded by nationality of winning firm (2023)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the TED database.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the TED database.

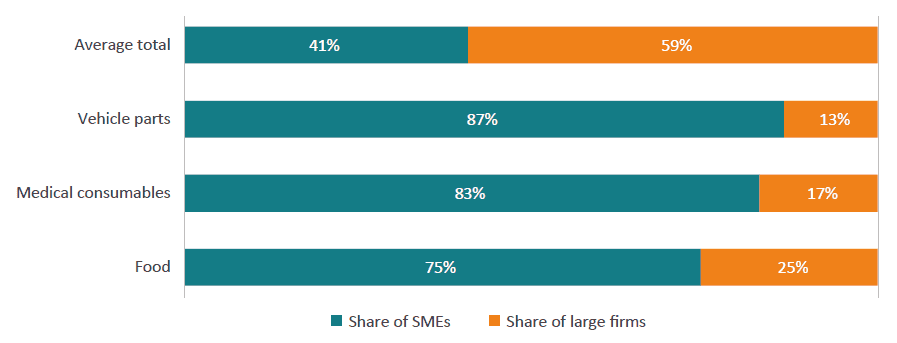

The TED database also provides valuable information about the size of bidding firms. On average, 41 percent of bids came from SMEs and 59 percent from large firms. However, averages mask wide disparities. In nearly half of all TED defence tenders in 2023, no SMEs submitted bids. These results point to stark differences in SME participation across product categories. Figure 5 shows that in some categories, such as vehicle parts, medical consumables and food, SMEs were the dominant bidders.

Figure 5: SME participation in defence procurement by product (TED Data, 2023)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the TED database.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the TED database.

[1] European Union. (n.d.). TED – European public procurement. https://ted.europa.eu/en/simap/european-public-procurement.

[2] European Union. (n.d.). Tenders Electronic Daily.https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/single-market/public-procurement/digital-procurement/tenders-electronic-daily_en.

[3] European Commission. (2016). Guidance on the award of government-to-government contracts in the fields of defence and security (Article 13(f) of Directive 2009/81/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C:2016:450:FULL.

[4] Wolff, G. & Mejino-López, J. (October 2025). Europe’s dependence on US foreign military sales and what to do about it. Bruegel. https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/europes-dependence-us-foreign-military-sales-and-what-do-about-it.

[5] European Defence Agency. (2024). Defence Data 2023-2024. https://eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/brochures/1eda—defence-data-23-24—web—v3.pdf.

[6] Kiel Institute for the Word Economy. (June 2025). Kiel Military Procurement Tracker. https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/kiel-military-procurement-tracker-33232/.

[7] Figure 2 lists 20 products by Common Procurement Vocabulary (CPV). CPV is a standardised classification system for goods, services, and works in European public procurement used to publish tenders on TED. The list of products and codes is the following: Battle tanks (35411000); Security equipment (35000000); Aircraft maintenance (50211210); Military aircrafts/missile maintenance (50650000); Gas oils (9134000); Motor vehicles (34100000); Construction work (45000000); Military vehicles (35400000); Kerosene (9131100); Building construction work (45210000); Concrete work (45262300); Weapons, ammunition (35300000); Petroleum (9130000); Construction military buildings (45216200); Military vehicles maintenance (50630000); Warship maintenance (50640000); Auxiliary research vessel (35513200); Software development (72000000); Flatbed trucks (34134100) and Furniture (39000000).

[8] The correlation between each member state’s share of tenders in TED and its share of overall EU defence spending in 2023 was 0.85.

[9] This includes also consortia consisting of: (1) purely domestic firms; (2) consortia with at least one other EU firm; and (3) consortia with at least one non-EU firm.

[10] Wolff, G. & Mejino-López, J. (October 2025). Europe’s dependence on US foreign military sales and what to do about it. Bruegel. https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/europes-dependence-us-foreign-military-sales-and-what-do-about-it.

[11] Maulny (2023) reports that 78 percent of defence acquisitions were sourced outside the EU between February 2022 and June 2023. However, the Kiel Report (No. 3, June 2025) argues that this figure may overstate reliance on foreign suppliers, as domestic purchases were excluded. The Bruegel US Foreign Military Sales database (Mejino-Lopez and Wolff, 2025), based on US FMS notifications, points to a sharp rise in potential US sales to European countries. Burilkov et al. (2025) note that total US exports of military equipment more than doubled in nominal terms between 2021 and 2024. While not exclusive to EU spending, this underscores the growing scale of US military exports, globally and to Europe.

4. Conclusions: Two Recommendations for a Stronger EU Defence Procurement Ecosystem

The case for a larger, integrated EU procurement market for defence is well established. Bigger markets deliver sharper competition, lower costs, and stronger incentives for innovation. They also allow firms to specialise, spreading research and development costs across a wider customer base. Defence, however, is not like any other market. It is bound tightly to national security, and governments have long shielded their industries from foreign competition. Yet Europe’s security will not be strengthened by 27 fragmented systems.

As George Washington once said: “To be prepared for war is one of the most effective means of preserving peace.”[1] European leaders have echoed this sentiment. At NATO, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen declared that “By 2030, Europe must have everything it needs for credible deterrence.”[2] In a joint op-ed, President Macron and Chancellor Merz committed to reforming procurement systems by applying the “three S’s”: standardisation, simplification and scale.[3] These statements point to the same truth: Europe cannot afford inefficiency in defence procurement.

These calls highlight why joint defence procurement must be central to Europe’s security system. As defence budgets grow year after year, the challenge is no longer whether money will be spent, but whether it will be spent wisely. Fragmented procurement wastes resources and undermines deterrence. A stronger European procurement market is therefore indispensable for security and economic efficiency. The findings of this Policy Brief point to two areas where change is possible and would bring positive results.

Recommendation 1: Breaking Home Bias in Non-Sensitive Procurement

A full EU defence procurement market will not be created overnight. Defence has been a national preserve for decades, and governments are used to channelling contracts to domestic champions. Our analysis shows that home bias is not confined to high-end strategic systems but extends even to routine goods and services where national security is not at stake. In 2023, three-quarters of all defence contracts in TED went to domestic firms. If Europe wants to change this pattern, it should start where the political resistance is weakest. A higher degree of EU-wide competition for non-sensitive defence products would create quick wins. Governments would benefit from lower costs and better quality, while winning European defence firms will be able to grow.

Recommendation 2: Improve Data and Analysis

Good policy requires good evidence, and in defence procurement the evidence is patchy. TED recorded only around €30 billion of defence contracts in 2023, compared with total defence spending of €280 billion across the EU. In other words, just one-tenth of procurement was visible in TED. National security exemptions explain part of the gap, but the fact that other research efforts, such as the Kiel Report, have assembled much larger datasets shows there is room for improvement. More information could be reported, and contracting authorities could make fuller use of TED.

Transparency and competitive procurement are not only a matter of academic curiosity but often, a legal obligation. Better data would allow EU and national policymakers to spot bottlenecks, measure progress and hold governments accountable for joint procurement pledges. Few policies are as vital as defence, and few areas would benefit more from greater transparency.

[1] Yale Law School Avalon Project (full 1790 address). First Annual Message of George Washington. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/washs01.asp.

[2] European Commission. (June 2025). Speech by President von der Leyen at the opening session of the NATO Summit Defence Industry Forum. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_25_1606 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

[3] Macron, E., & Merz, F. (June 2025). Macron and Merz: Europe must arm itself in an unstable world. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/c1bf5fe8-602d-4887-a5eb-1bd247be9d54.

References

Burilkov, A., J. Mejino-Lopez, & G. Wolff. (2024). The US defence industrial base can no longer reliably supply Europe. Bruegel Analysis. https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2024-12/theus-defence-industrial-base-can-no-longer-reliably-supply-europe-10561.pdf

Draghi, M., & Letta, E. (2024). The future of European competitiveness. https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-competitiveness/draghi-report_en

EUR-Lex. (May 2021). Regulation (EU) 2021/697 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2021 establishing the European Defence Fund and repealing Regulation (EU) 2018/1092. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32021R0697

European Commission (November 2025). Commission moves towards ‘Military Schengen’ and transformation of defence industry. https://transport.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/commission-moves-towards-military-schengen-and-transformation-defence-industry-2025-11-19_en

European Commission. (July 2025). Europe’s Budget – Defence. https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/e2aa6ac7-9920-4ec6-97fe-399dd5561e54_en?filename=MFF_Defence_16.07.pdf.

European Commission. (June 2025). Speech by President von der Leyen at the opening session of the NATO Summit Defence Industry Forum. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_25_1606.

European Commission. (May 2025). The economic impact of higher defence spending.https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/economic-forecast-and-surveys/economic-forecasts/spring-2025-economic-forecast-moderate-growth-amid-global-economic-uncertainty/economic-impact-higher-defence-spending_en.

European Commission. (March 2025). Questions and answers on ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_25_790.

European Commission. (November 2024) EU boosts defence readiness with first ever financial support for common defence procurement. https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/eu-boosts-defence-readiness-first-ever-financial-support-common-defence-procurement-2024-11-14_en

European Commission. (March 2024). A new European Defence Industrial Strategy: Achieving EU readiness through a responsive and resilient European Defence Industry. https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/document/download/643c4a00-0da9-4768-83cd-a5628f5c3063_en?filename=EDIS%20Joint%20Communication.pdf

European Commission. (2016). Guidance on the award of government-to-government contracts in the fields of defence and security (Article 13(f) of Directive 2009/81/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C:2016:450:FULL.

European Commission. (November 2016). European Defence Action Plan. https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/20372

European Commission. (n.d.). EDIP | A Dedicated Programme for Defence. https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/eu-defence-industry/edip-dedicated-programme-defence_en

European Commission. (n.d.). EDIRPA | Procuring together defence capabilities. https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/eu-defence-industry/edirpa-addressing-capability-gaps_en

European Commission. (n.d.). EDIS | Our common defence industrial strategy. https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/eu-defence-industry/edis-our-common-defence-industrial-strategy_en

European Commission. (n.d.). European Defence Industrial Development Programme (EDIDP). https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/eu-defence-industry/european-defence-industrial-development-programme-edidp_en

European Commission. (n.d.). Preparatory Action on Defence Research (PADR). https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/eu-defence-industry/preparatory-action-defence-research-padr_en

European Union. (n.d.). TED – European public procurement. https://ted.europa.eu/en/simap/european-public-procurement.

European Union. (n.d.). Tenders Electronic Daily.https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/single-market/public-procurement/digital-procurement/tenders-electronic-daily_en.

European Defence Agency. (2025). Defence Data 2024-2025. https://eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/brochures/2025-eda_defencedata_web.pdf

European Defence Agency. (2024). Defence Data 2023-2024. https://eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/brochures/1eda—defence-data-23-24—web—v3.pdf

European Defence Agency. (2007). Defence Data 2007. https://eda.europa.eu/docs/default-source/brochures/2025-eda_defencedata_web.pdf

Howorth, J. (2014). Security and Defence Policy in the European Union (2nd ed.). (The European Union Series). Palgrave Macmillan.

Kiel Institute for the World Economy. (June 2025). Kiel Military Procurement Tracker. https://www.ifw-kiel.de/publications/kiel-military-procurement-tracker-33232/.

Macron, E., & Merz, F. (June 2025). Macron and Merz: Europe must arm itself in an unstable world. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/c1bf5fe8-602d-4887-a5eb-1bd247be9d54.

Maulny, J. P. (2023). The impact of the war in Ukraine on the European defence market. IRIS Policy Paper.

Mejino-Lopez, J., &G. Wolff. (2024). A European defence industrial strategy in a hostile world. Bruegel Policy Brief 29-2024. https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/PB%2029%202024.pdf.

Napolitano, A., & Wagemans, D. (2025). Europe’s Defence Crisis: Why More Spending Alone Will Not Keep the Continent Safe. Social Europe. https://www.socialeurope.eu/europes-defence-crisis-why-more-spending-alone-will-not-keep-the-continent-safe.

Yale Law School Avalon Project. (full 1790 address). First Annual Message of George Washington. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/washs01.asp

Wolff, G. & Mejino-López, J. (October 2025). Europe’s dependence on US foreign military sales and what to do about it. Bruegel. https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/europes-dependence-us-foreign-military-sales-and-what-do-about-it.