More Than Just Chips: What Europe Can Learn from Taiwan’s Industrial Strategy

Published By: Andrea Dugo Dyuti Pandya

Research Areas: Data, AI, and Emerging Technologies EU Single Market, Institutions, and Governance Far East Industrial and Competitiveness Policy

Tags: EU industrial policy R&D Taiwan

Summary

Taiwan is widely regarded as the global epicentre of semiconductor manufacturing. The island accounts for well over half of all global chip foundry manufacturing and nearly all of advanced chip output. At the heart of this system stands the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which alone contributes 8.9 per cent of national GDP and dominates the world’s leading-edge logic foundry market. Yet framing Taiwan’s economic success as a TSMC story risks oversimplifying both its growth model and the policy lessons it offers.

Taiwan’s competitiveness is best understood not as the product of semiconductors alone, but as the outcome of a broader industrial ecosystem. Taiwan had already reached advanced-economy income levels in the late 1990s, when chips still accounted for only a modest share of national output. Importantly, growth remains broad-based, with substantial contributions still coming from the wider industrial economy. The semiconductor sector’s decisive contribution has not been to “create” Taiwan’s prosperity, but to accelerate its transformation into a technological frontrunner. Counterfactual estimates suggest that without chips, Taiwan would remain a high-income economy – but it would lose much of its current convergence momentum with the world’s innovation leaders.

Taiwan’s economic model is defined by its intense focus on innovation. The island ranks third globally in R&D expenditure as a share of GDP, with roughly 4 per cent of output devoted to R&D. Crucially, around 86 per cent of this spending is performed by firms rather than the public sector, ensuring that innovation remains closely tied to production capability and market demand. R&D investment is heavily weighted towards experimental development, which turns research into final prototypes and commercial products. Even excluding chips, Taiwan’s business R&D intensity would remain higher than that of 19 of the EU’s 27 Member States.

This success has been engineered through deliberate, long-term statecraft that evolved from “state-led creation” to “state-enabled upgrading.” In earlier decades, institutions such as the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) helped Taiwan acquire and adapt foreign technologies, train engineers, and build pre-commercial capabilities. But Taiwan avoided locking itself into permanent state ownership and subsidy dependence: firms incubated in public settings were progressively spun off and pushed towards market validation, including the creation of global champions such as TSMC.

From the 1990s onwards, Taiwan’s industrial strategy increasingly prioritised horizontal support measures rather than heavy-handed state intervention. The Taiwanese model consolidated around five reinforcing policy levers: (1) a state role focused on enabling private R&D rather than substituting for it; (2) sustained investment in human capital; (3) science park clustering; (4) deep integration into global trade and value chains; and (5) diversification and spillovers into adjacent high-tech sectors.

For European policymakers, Taiwan’s experience suggests that subsidies alone do not constitute an industrial strategy. Instead, the central lesson is ecosystem-building: policies that connect research to scaling, talent to industrial capability, and innovation to globally competitive production. Ultimately, Taiwan offers a model of how public policy can shape innovation capacity and competitiveness without displacing private-sector dynamism.

1. Introduction

Integrated circuits – better known as “microchips”, or simply “chips” – have become a strategic input for modern economies. They underpin not only consumer electronics, but also the deployment of frontier technologies such as AI, advanced communications systems, and emerging computing paradigms. As a result, semiconductors are no longer just an industrial commodity: they are now central to economic security, productivity growth, and geopolitical influence.

For policymakers in Europe and other advanced economies, Taiwan’s paramount role in the global semiconductor system is therefore not simply an industrial success story, but a critical exposure in the architecture of global value chains. Taiwan accounts for roughly 60 per cent of global semiconductor production (chip foundry manufacturing), and about 90 per cent of advanced chip output.[1] Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) alone is widely cited as controlling the majority of the world’s leading-edge logic foundry market. This makes Taiwan a focal point of both the global race for technological leadership and the debate about supply-chain resilience.

At the same time, interpreting Taiwan’s competitiveness as synonymous with TSMC and chips risks missing the underlying policy lesson. Taiwan’s position at the frontier is not the product of a single company or sector alone, but of an ecosystem that can industrialise technology reliably, quickly, and repeatedly. Semiconductors sit at the centre of this system, but Taiwan’s advantage rests on a broader web of capabilities spanning design, advanced manufacturing, packaging and testing, and deep integration into global hardware value chains.

Taiwan’s success is therefore best understood as the outcome of long-run statecraft in innovation and industrial strategy: a model that combines sectoral direction-setting with horizontal investment incentives, state-built innovation infrastructure, cluster development, and later-stage coordination tools such as IP mechanisms, venture capital platforms, and institutional support for continuous upgrading. In a world where industrial policy has returned to the centre of economic strategy, Taiwan offers Europe a concrete case study of how public policy can shape innovation capacity without displacing private-sector dynamism.

[1] ITA. (2025). Semiconductors including chip design for AI. Available at: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/taiwan-semiconductors-including-chip-design-ai ; Global Taiwan Institute. (2025). Taiwan’s shortage of chipmakers: A major threat to the industry’s long-term growth. Global Taiwan Brief, 10(5). https://globaltaiwan.org/2025/03/taiwans-shortage-of-chipmakers-a-major-threat-to-the-industrys-long-term-growth/

2. The Making of a Technology State

2.1 How Taiwan Built a Semiconductor Industry from Scratch

Taiwan’s turn towards high-technology manufacturing began in the 1970s, when policymakers set out to transform a largely agrarian economy with pockets of low-tech manufacturing into a high-technology powerhouse. This strategy relied on the deliberate transfer of critical technologies from the US and the creation of dedicated public research institutions and state-backed firms to anchor the effort.

Unlike Japan and South Korea, Taiwan lacked large, long-established corporate conglomerates capable of spearheading industrial transformation. Instead, it built its high-tech sector largely from scratch, drawing on the skills and entrepreneurship of engineers, technologists, and policymakers, many of whom had acquired formative experience in Silicon Valley.[1] The ecosystem that emerged blended public coordination with private initiative, laying the foundations for Taiwan’s later success.

Since most Taiwanese firms were still too small to sustain serious R&D on their own, the government’s push to upgrade domestic technological capabilities relied on building shared innovation capacity. The first – and most important – industrial policy initiative was therefore the creation in 1973 of the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI), a state-backed innovation platform designed to accelerate technology upgrading across the economy.[2]

ITRI’s function was not simply to conduct research, but to close the innovation gap facing small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). It did so by (1) acquiring and assimilating foreign technologies and adapting them to domestic needs; (2) providing technical services and training to firms; and (3) moving technologies into pre-commercial and pilot stages, enabling the private sector to scale production and compete internationally.

Crucially, Taiwan used ITRI as a public catalyst without locking industries into permanent state ownership. Commercial ventures initiated within ITRI were spun off into separate firms and pushed towards market validation, making sure they would attract non-government funding, hence avoiding long-term dependency on public subsidies.

The semiconductor sector is the clearest example of the success of this ITRI-driven strategy. After identifying promising niches in the semiconductor value chain, acquiring technology from abroad, and building capabilities through targeted training and pilot production, ITRI spun off Taiwan’s two flagship semiconductor firms in the 1980s: TSMC and United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC).

While ITRI dominated Taiwan’s semiconductor industrial policy in the 1970s and 1980s, two complementary policy levers reinforced this trajectory. First, the creation of Hsinchu Science Park concentrated high-tech and semiconductor activity into a dedicated cluster, strengthened by proximity to universities and applied research collaboration. Second, returning overseas Taiwanese talent, particularly from the US technology ecosystem, brought technical expertise, managerial experience, and international networks that accelerated the development of a globally competitive semiconductor base.

Initially, the semiconductor sector’s economic footprint remained modest. Between the early 1980s and the mid-1990s, chips contributed roughly 1.5–2 per cent of Taiwan’s GDP. However, as the global computer industry expanded in the late 1990s, that contribution began to rise.

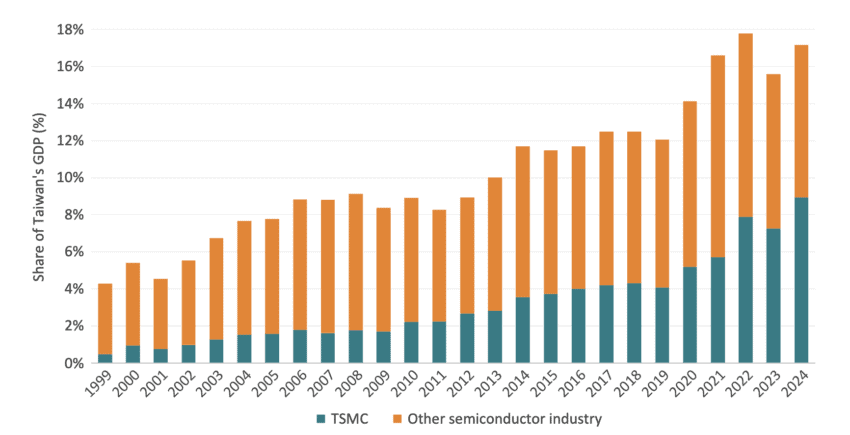

Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of value added by TSMC and the broader semiconductor industry as a share of Taiwan’s GDP between 1999 and 2024. In 1999, the sector accounted for just over 4 per cent of GDP – important, but far from indispensable. TSMC alone represented around 0.5 per cent, less than one-eighth of the industry’s total contribution.

Over the past 25 years, the picture has changed fundamentally. The semiconductor industry has become a central pillar of Taiwan’s economy, with TSMC by far its most relevant player. The chip sector now accounts for more than 17 per cent of national value added. TSMC alone contributes 8.9 per cent of GDP – more than half of the sector’s total. For comparison, this is roughly equivalent to the entire tech sector’s contribution to US GDP[3] and almost three percentage points more than Germany’s automotive industry,[4] which accounts for around 6 per cent of national output.

Figure 1: Value added of TSMC and the semiconductor industry as a share of Taiwan’s GDP, 1999–2024 Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from National Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan) and TSMC’s Financial Statements 1999–2024. Note: TSMC’s value added in Taiwan was calculated for each year following the methodology set out in TSMC’s Sustainability Impact Valuation Reports 2023 and 2024.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from National Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan) and TSMC’s Financial Statements 1999–2024. Note: TSMC’s value added in Taiwan was calculated for each year following the methodology set out in TSMC’s Sustainability Impact Valuation Reports 2023 and 2024.

TSMC has, in effect, become Taiwan’s most important company, on a scale rarely matched in other advanced economies. The firm alone also accounts for roughly 50–60 per cent of the capitalisation of Taiwan’s stock exchange and ranks as the world’s ninth-largest company by market value, as well as the largest listed company outside the US. In this light, it is easy to see why Taiwan is often described not as a country that happens to host a leading chipmaker, but as a chipmaker endowed with nationhood.

2.2 Beyond TSMC and Semiconductors: Taiwan’s Broader Growth Story

The view that Taiwan owes its economic success solely to TSMC and the semiconductor industry is commonly shared, and not completely without reason. Yet equating Taiwan’s competitiveness only with its chip sector risks obscuring the broader strength and resilience of its economy. It is worth recalling that in the late 1990s, when the semiconductor industry was only beginning to expand, Taiwan’s GDP per capita already firmly placed it among advanced economies by IMF standards.[5]

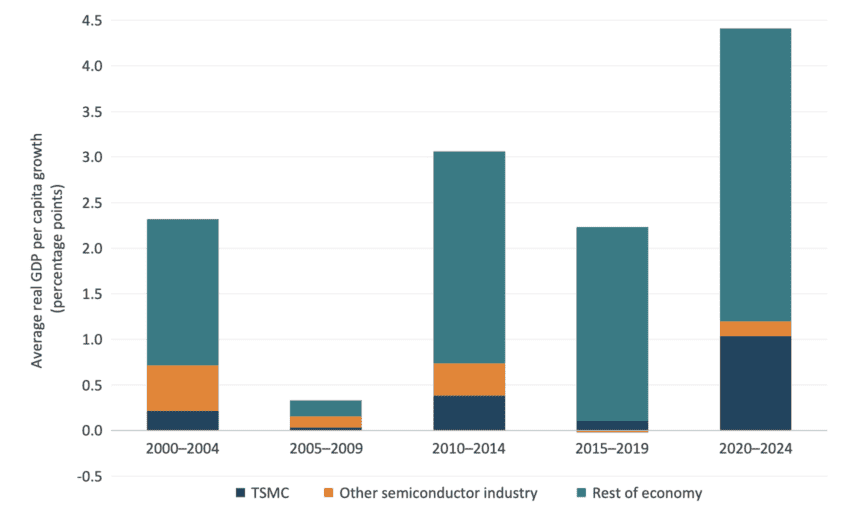

While rising prosperity in Taiwan has clearly been supported by TSMC and the wider semiconductor industry, this contribution has unfolded within the broader context of an already fast-growing economy. Figure 2 decomposes Taiwan’s average real GDP per-capita growth over five five-year periods between 2000 and 2024 into the respective contributions of TSMC, the rest of the semiconductor industry, and the remainder of the economy.

The chart shows that growth in Taiwanese prosperity has remained broad-based over time, even as the contribution of the semiconductor sector has increased. Throughout the period, TSMC and the wider chip industry have contributed to GDP per-capita growth in disproportionately positive terms relative to their size in the economy. This is most evident in the most recent period (2020–2024), when average per-capita growth accelerated and TSMC emerged as a major driver, reflecting the surge in global demand for advanced chips. Despite accounting for around 9 per cent of GDP, TSMC alone contributed up to a quarter of average annual real per-capita growth.

At the same time, a substantial share of growth continued to come from the rest of the economy. This underlines that Taiwan’s recent prosperity – while increasingly supported by semiconductors – has not been driven by the chip sector alone. In short, the contribution of TSMC and the semiconductor industry to rising prosperity in Taiwan is both critical and far larger than their direct economic weight, but it operates within the context of an economy that remains fast-growing and resilient.

Figure 2: Contributions to real GDP per capita growth in Taiwan, by sector, 2000–2024 Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from National Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan) and TSMC’s Financial Statements 1999–2024. Note: Contributions are calculated as differences in average log growth rates of real GDP per capita, expressed in constant 2015 US dollars and deflated using Consumer Price Indices by Basic Group.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from National Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan) and TSMC’s Financial Statements 1999–2024. Note: Contributions are calculated as differences in average log growth rates of real GDP per capita, expressed in constant 2015 US dollars and deflated using Consumer Price Indices by Basic Group.

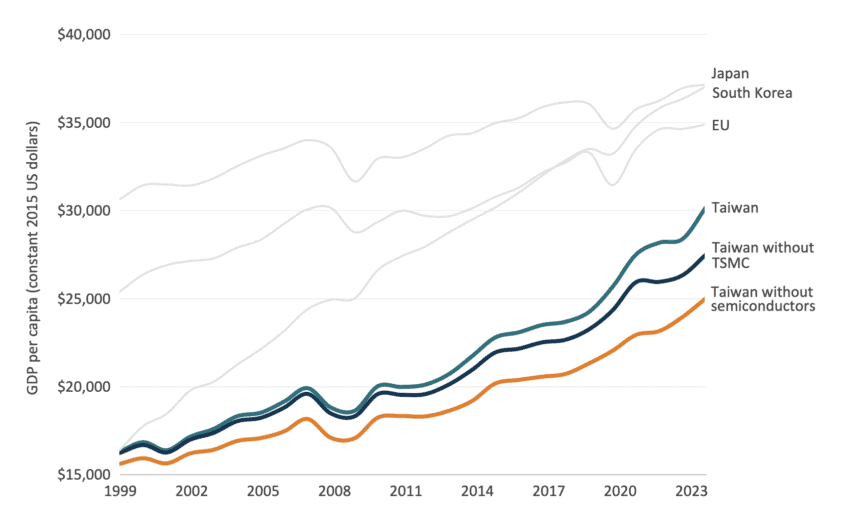

Another instructive way to assess the importance of Taiwan’s semiconductor industry for economic prosperity is to ask how Taiwan’s growth trajectory would look in its absence – either without TSMC specifically, or more radically, without a domestic semiconductor industry altogether. Figure 3 addresses this question by plotting Taiwan’s real GDP per capita over the period 1999–2024 under three scenarios: the observed baseline, a counterfactual in which TSMC does not exist, and a counterfactual in which the entire Taiwanese semiconductor industry is removed. These trajectories are shown alongside those of Japan, South Korea, and the EU.

These counterfactuals are inevitably stylised. GDP per capita excluding TSMC or the semiconductor sector is calculated by subtracting their direct gross value added from Taiwan’s GDP, while holding population constant. As such, the exercise captures the direct accounting contribution to GDP per capita and abstracts from broader general-equilibrium effects, including labour reallocation, spillovers, migration, and the indirect impact that the absence of TSMC or the chip industry would have on other parts of the economy. Even with these limitations, the comparison is telling.

Absent the semiconductor sector altogether, Taiwan’s real GDP per capita would be around USD 5,000 lower. Even so, Taiwan would still rank firmly among developed economies, with income levels somewhere between those of Saudi Arabia and Slovenia. What the semiconductor industry, and TSMC in particular, has enabled is not Taiwan’s transition into a developed economy per se, but its elevation into a substantially more prosperous one.

According to current-price estimates,[6] Taiwan has already reached GDP per capita levels higher than those of Japan and South Korea, though not the EU. When measured in inflation-adjusted terms, however, convergence remains incomplete. If Taiwan were to sustain the exceptional, TSMC-driven growth performance observed between 2020 and 2024, it would converge to Japanese and EU income levels by the early 2030s, and to those of South Korea by the late 2030s. Absent TSMC, this convergence would be dramatically delayed: alignment with Japan would move into the mid-2040s, with the EU pushed out to the 2070s, and convergence with South Korea would disappear altogether within any policy-relevant horizon.

Put differently, stripping out its flagship chipmaker would leave Taiwan an advanced – and even relatively fast-growing – economy, but not the frontier economy it has become today.

Figure 3: Taiwan’s real GDP per capita with and without TSMC and semiconductors, 1999–2024 Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from National Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan), the World Bank, and TSMC’s Financial Statements 1999–2024. Note: GDP per capita is expressed in constant 2015 US dollars; for Taiwan, values are deflated using Consumer Price Indices by Basic Group.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from National Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan), the World Bank, and TSMC’s Financial Statements 1999–2024. Note: GDP per capita is expressed in constant 2015 US dollars; for Taiwan, values are deflated using Consumer Price Indices by Basic Group.

[1] Tinn, H. (2025). Island Tinkerers: Innovation and Transformation in the Making of Taiwan’s Computing Industry. MIT Press.

[2] Wong, C. Y. (2022). Experimental Learning, Inclusive Growth and Industrialised Economies in Asia. Springer Books.

[3] Statista. (2025, November 28). Tech GDP as a percent of total GDP in the U.S. 2017–2023. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1239480/united-states-leading-states-by-tech-contribution-to-gross-product/

[4] Motor Finance. (2025, March 5). Germany’s auto sector faces structural shifts as sales decline. Available at: https://www.motorfinanceonline.com/features/germanys-auto-sector-faces-structural-shifts-as-sales-decline/

[5] IMF. World Economic Outlook Database – The World Economic Outlook (WEO) Database April 1999. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/publications/weo/weo-database/1999/april

[6] McCartney, M. (2025, December 23). Asia’s economies ranked after Taiwan overtakes South Korea. Newsweek. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/asias-economies-ranked-after-taiwan-overtakes-south-korea-11258065

3. Taiwan’s Innovation Ecosystem: Beyond the Foundry

3.1 Semiconductors and the Electronics Industry: What Sets Taiwan Apart

Taken together, the counterfactuals show that semiconductors have been decisive in elevating Taiwan from a high-income economy to a global technological frontrunner. But they do not, by themselves, explain why Taiwan’s semiconductor sector has generated such an outsized and persistent impact. To understand this, it is necessary to move beyond aggregate growth figures and examine the underlying structure of Taiwan’s semiconductor and electronics industry.

Taiwan’s economic success cannot be reduced to chip manufacturing alone. Rather, the semiconductor sector has been embedded within a much broader electronics and industrial ecosystem. In addition to leading-edge fabrication,[1] Taiwanese firms have also emerged as global leaders in semiconductor packaging and testing,[2] while maintaining a meaningful presence in chip design and upstream materials such as wafer substrates and other critical inputs. This breadth, spanning multiple stages of the semiconductor value chain, extends well beyond logic manufacturing alone. This becomes particularly consequential in the context of AI. Modern AI accelerators require not only advanced logic chips but also sophisticated packaging to integrate high-bandwidth memory (HBM). Even when the memory itself is supplied by Korean or US firms, much of the final integration, advanced packaging, and testing takes place in Taiwan.[3]

Firms such as UMC, MediaTek, and Advanced Semiconductor Engineering (ASE), among others, reinforce Taiwan’s central role across design, manufacturing, packaging, and materials, underscoring the sophistication of its semiconductor ecosystem, including a leading OSAT (outsourced semiconductor assembly and test) ecosystem.

Unsurprisingly, Taiwan is also home to some of the world’s most influential electronics firms. Asus, the world’s fifth-largest computer maker,[4] has expanded aggressively into mini PCs, gaming hardware, and smart manufacturing solutions. Hon Hai Precision Industry Co. better known as Foxconn, remains the world’s largest electronics contract manufacturer and the primary assembler of Apple’s iPhone, anchoring Taiwan’s role in global consumer electronics supply chains. Taiwan is therefore a leading producer of flat-panel displays, consumer electronics, and network equipment, while its machinery sector supplies critical tools and equipment used across global manufacturing industries.

Emerging industrial segments including green energy technologies, biotechnology, and precision machinery further reinforce this ecosystem and remain closely linked to advances in semiconductors and electronics more generally. In 2024, Taiwan again recorded growth in industrial production, reflecting both cyclical recovery and structural competitiveness. Today, Taiwan accounts for approximately 80 per cent of global laptop and motherboard production and around 60 per cent of the world’s network devices,[5] highlighting its dominance in downstream electronics manufacturing.

The importance of this ecosystem is especially evident in complex consumer products such as the iPhone, which contains roughly 1,500 components.[6] In teardown estimates for recent models, components and materials sourced from Taiwanese firms – including core processors and other high-value parts – have been estimated to represent a substantial portion of the device’s materials bill, a share frequently cited at around one-third of total materials cost in past analyses. Moreover, analyses of Apple’s supplier network show that Taiwan accounts for 20 per cent of top 200 suppliers among all countries, pointing to its deep integration into high-value segments of global electronics production. Put differently, and as industry insights suggest, chips are manufactured in Taiwan, mounted onto Taiwanese printed circuit boards (PCBs), and shipped to China for final assembly.

This breadth of capability reveals a deeper truth: Taiwan’s economic success rests on the continuous interplay between semiconductor leadership, electronics manufacturing, system integration, and firm-level innovation. It is this mutually reinforcing industrial ecosystem that has sustained Taiwan’s competitiveness over several decades.

3.2 Innovation, More Than Chips, is at the Heart of Taiwan’s Economic Model

As we at ECIPE have shown in previous country case studies such as with South Korea and Switzerland, economic growth, productivity gains and broad-based prosperity are closely linked to sustained investment in innovation.[7] Taiwan is no exception. The island economy ranks third worldwide in R&D expenditure as a share of GDP,[8] behind only Israel and South Korea.

An examination of the composition of R&D spending, by type,[9] reveals that a significant share is devoted to experimental development. Approximately 74 per cent of total R&D expenditure falls into this category, indicating an innovation ecosystem with advanced capabilities focused on translating research into final prototypes, process optimisation, and commercial products. This structure suggests that Taiwan has moved well beyond a reliance on basic and applied research alone and is now firmly oriented towards late-stage development and market deployment.

The share of applied research within total R&D expenditure has declined gradually, from 23.1 percent in 2015 to 18.3 percent in 2024. This shift reflects the maturation of Taiwan’s innovation system: as core technologies have stabilised, R&D has increasingly shifted towards experimental development and late-stage commercialisation. High-technology industries now account for roughly 69 per cent of total R&D expenditure, underscoring the long-standing policy focus on IT hardware and electronics as central pillars of the economy.

As in most innovation-driven economies, the overwhelming majority of R&D in Taiwan – more than 86 per cent – is performed by firms rather than the public sector. This private-sector dominance is closely linked to Taiwan’s strong innovation performance. In particular, more than 80 per cent of business R&D is devoted to experimental development, compared with less than half in government and other non-business institutions.

Firms are generally better positioned than public and other non-private entities to convert ideas into scalable products, processes, and commercial applications. By concentrating R&D within companies, Taiwan’s innovation system ties research more directly to production, investment, and market demand – conditions that are far more conducive to productivity gains and long-run growth than systems led primarily by public research.

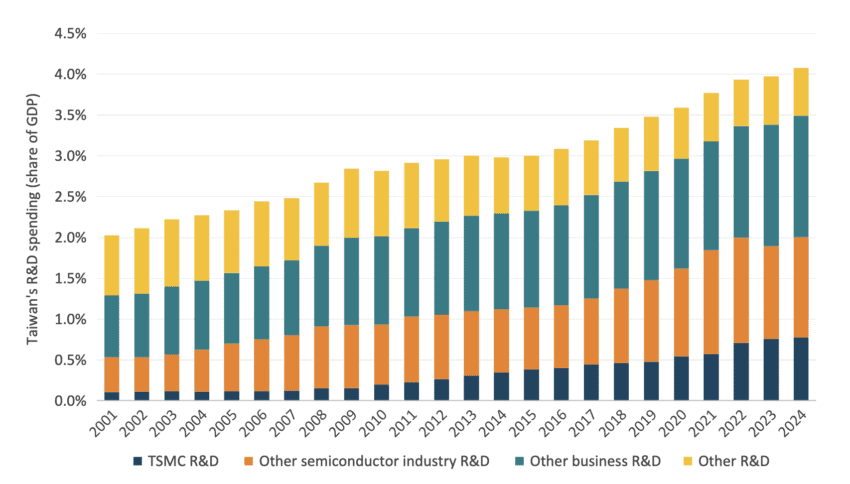

This private-sector dominance, however, is not a static feature of Taiwan’s economy; it is the outcome of a long-running structural transformation in how R&D is financed and performed. Figure 4 illustrates the evolution of Taiwan’s R&D expenditure by performer between 2001 and 2024, distinguishing between TSMC, the rest of the semiconductor industry, the broader private sector, and other R&D spending.

The transformation over time is striking. In 2001, Taiwan devoted roughly 2 per cent of GDP to R&D, with less than two-thirds of that expenditure undertaken by the business sector. At the time, the semiconductor industry accounted for around 0.5 per cent of GDP, roughly one quarter of total R&D spending – and TSMC represented just 0.1 per cent.

Today, the picture has changed dramatically. Taiwan now invests around 4 per cent of GDP in R&D – double its level a quarter of a century earlier – and no less than 86 per cent of this spending is performed by the private sector. The semiconductor industry now accounts for half of Taiwan’s total R&D spending and has quadrupled in GDP terms, rising from 0.5 per cent in 2001 to 2 per cent today. Within this, TSMC alone has increased its R&D expenditure eightfold, from 0.1 to 0.8 per cent of GDP. R&D investment in the rest of the private sector has also expanded substantially, albeit at a slower pace, doubling from 0.75 per cent of GDP in 2001 to 1.5 per cent in 2024.

Put differently, Taiwan’s ascent to the top tier of global R&D spenders over the past 25 years is overwhelmingly the result of sustained increases in private-sector innovation investment, led by TSMC and the semiconductor industry, but reinforced by a broader rise in business-driven R&D across the economy.

Crucially, this expansion in private-sector R&D has been highly concentrated in engineering and technology fields, a pattern that has remained remarkably stable over time.[10] While the source of R&D funding has shifted decisively towards the private sector, the focus of that spending has consistently remained on high-tech industries.

Figure 4: Taiwan’s R&D spending as a share of GDP by performer, 2001–2024 Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the National Science and Technology Survey and TSMC’s Financial Statements 1999–2024.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the National Science and Technology Survey and TSMC’s Financial Statements 1999–2024.

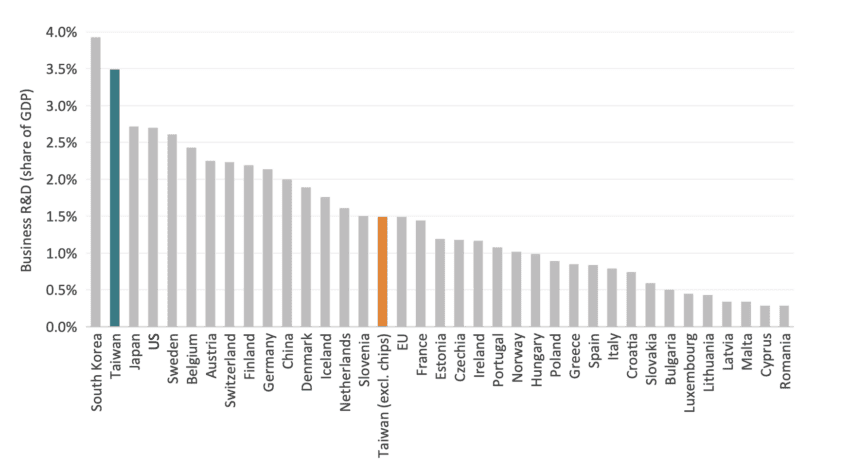

The importance of innovation spending, particularly from the private sector, in Taiwan’s economic success becomes especially clear when set against other advanced economies. Figure 5 compares selected developed economies in Europe, East Asia and the US, ranking them by business R&D expenditure as a share of GDP. As with total R&D intensity, Taiwan ranks just below South Korea and above all other countries, with privately funded R&D amounting to 3.5 per cent of GDP (see the green bar).

What is equally striking, however, is how Taiwan would perform if its semiconductor industry were entirely excluded (see the orange bar). Even after removing semiconductor R&D – which, as shown earlier, currently accounts for roughly 2 per cent of GDP – Taiwan would still record business R&D spending of around 1.5 per cent of GDP from the rest of the economy. While this would clearly displace Taiwan from the global podium of top R&D spenders, it would still represent a solid international performance.

Indeed, even without the chip sector, Taiwan’s business R&D intensity would remain slightly above that of the EU as a whole. Individually, Taiwan would still outspend 19 of the EU’s 27 Member States in business R&D as a share of GDP.

Put differently, much as with GDP per capita, Taiwan without semiconductors would remain a mid- to high-innovation economy; it is ultimately the semiconductor industry, however, that propels the country into the upper tier of global frontier innovation.

Figure 5: Business R&D spending as a share of GDP in selected advanced economies, with and without Taiwan’s semiconductor industry, 2024 Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the National Science and Technology Survey and Eurostat.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the National Science and Technology Survey and Eurostat.

[1] Reinsch, A. W., & Whitney, J. (2025). Silicon island: Assessing Taiwan’s importance to U.S. economic growth and security. CSIS. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/silicon-island-assessing-taiwans-importance-us-economic-growth-and-security

[2] Kennedy, P. (2025). Why Taiwan fears ‘America First’ risks eroding its ‘silicon shield’. Stimson Center. Available at: https://www.stimson.org/2025/why-taiwan-fears-america-first-risks-eroding-its-silicon-shield/

[3] Chang, J. C.-C., & Chiu, Y.-N. (2025, November 17). Beyond competition in the AI era: Taiwan–Korea semiconductor cooperation. Korea on Point. Available at: https://koreaonpoint.org/articles/article_detail.php?idx=492

[4] Fang, T.-C. (2023, November 21). Taiwan’s top computer maker to produce servers in US to tap AI boom. Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/07fc44a3-873a-4cc0-91f4-5918b3bbe469

[5] CSIS. (2022). Why Taiwan Matters – From an Economic Perspective. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/why-taiwan-matters-economic-perspective

[6] Li, L., & Fang, T.-C. (2023, May 31). How Taiwan became the indispensable economy. Financial Times. Available at: https://ig.ft.com/taiwan-economy/

[7] Dugo, A. (2024). South Korea versus Japan: What can the EU learn from the two countries? ECIPE Insights. Available at: https://ecipe.maintenance-02-monocode.site/insights/south-korea-versus-japan-what-can-the-eu-learn-from-the-two-countries/ and Dugo, A. (2024). Sweden vs Switzerland: A heavyweight champions fight on innovation. ECIPE Insights. Available at: https://ecipe.maintenance-02-monocode.site/insights/sweden-vs-switzerland-a-heavyweight-champions-fight-on-innovation/

[8] Neufeld, D. (2025, April 17). Technology ranked: Countries investing the most in R&D. Visual Capitalist. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/rd-investment-by-country/

[9] NSTC. (2024). R&D Expenditure by Type of R&D. Available at: https://wsts.nstc.gov.tw/stsweb/technology/TechnologyDataIndex.aspx?language=E

[10] NSTC. (2024). Business Enterprise R&D Expenditure by Feld of Research and Development (FORD). Available at: https://wsts.nstc.gov.tw/stsweb/technology/TechnologyDataIndex.aspx?language=E

4. Industrial Policy Done Right: Lessons for Europe

4.1 Designed for Success: How Taiwan Engineered its Innovation Miracle Through Policy

Taiwan’s innovation-led growth from the 1990s onwards was not the product of chance. It was the result of a deliberate and sustained industrial policy strategy. Having built domestic technological foundations – in semiconductors and across the wider electronics sector – through the 1970s and 1980s, the 1990s marked the transition to the consolidation phase. Taiwan’s innovation model emerged as the government sought to scale its achievements and anchor them in an increasingly globalised market.

While Taiwan’s approach evolved across different phases, the post-1990s model broadly shifted away from policies primarily aimed at creating industries towards policies designed to deepen, coordinate, and govern a more mature innovation ecosystem. Over the past three decades, five recurring policy levers stand out as the pillars through which Taiwan sustained and operationalised its innovation model:

- State shift from investor to enabler of private R&D

- Human capital and talent

- Science park clusters

- Trade and global value chain integration

- Diversification and technological spillover

The first policy approach has been to reposition the state from a direct public investor and hands-on facilitator to an enabler and mediator of predominantly private R&D. While direct subsidies[1] and other vertical industrial policy instruments did not disappear entirely, from the 1990s onwards the government markedly reduced its role compared to earlier decades,[2] allowing the private sector to take the lead in science and technology development. Public bodies increasingly focused on horizontal policies designed to create the conditions for private R&D to flourish.

Legislation such as the 1999 Fundamental Science and Technology Act provided a clearer legal basis for technology policy formulation, including government support for schools and research institutes and the development of science and technology personnel. This broader shift towards less interventionist governance was also reflected in ITRI’s activities, including the provision of IP-support mechanisms (such as an IP bank and patent pools) and related services to assist startups, strengthen firms’ patent portfolios, and reduce exposure to litigation, alongside the creation of supporting infrastructure such as venture capital funds for new startups.

The second policy instrument has been human capital and talent policy. Alongside continued efforts to incentivise the return of Taiwanese talent from abroad, the government from the 1990s onwards began to embed domestic talent development in clearer frameworks and longer-term strategies.[3] The 1999 Fundamental Science and Technology Act, for instance, placed explicit emphasis on strengthening the science and technology workforce through assistance to public schools, research institutes, and enterprises, as well as through the systematic development of scientific and technological personnel.

Talent policy also operated through stronger university–industry linkages. National Tsing Hua University and National Chiao Tung University played an important role in this regard, with professors establishing laboratories in partnership with firms, graduates being recruited by industry collaborators, and spinoffs emerging from these networks. The most significant recent impulse, however, has come under the former Tsai administration from 2016 onwards.[4] Through the “5+2 Industrial Innovation Plan,” the government sought to deepen the human capital pillar further by expanding interdisciplinary digital skills, strengthening expert training mechanisms, and improving the recruitment and retention of international top talent.

The third policy strategy has been the promotion of science park clusters. Although the first stone of Taiwan’s science park system was laid in the 1980s with the establishment of Hsinchu Science Park, it was from the 1990s onwards that cluster-specific policy was more systematically deployed to cultivate techno-entrepreneurs and accelerate the expansion of high-tech industries, particularly semiconductors, which became the park’s dominant sector. This development was soon followed by the establishment of two other science parks: the Central Taiwan Science Park and the Southern Taiwan Science Park.

Unlike science parks in many other countries, which evolved primarily as manufacturing-oriented clusters designed to link R&D directly with large-scale production, Taiwan’s science park system remained closely aligned with the country’s technological frontier. Within these parks, R&D activity became concentrated in high-technology industries – especially integrated circuits, computers and peripherals, telecommunications, optoelectronics, precision machinery, and biotechnology – with a strong emphasis on experimental development.[5] By co-locating firms, specialised suppliers, and skilled labour, Taiwan’s science park model generated powerful agglomeration effects, reducing costs, accelerating learning, and enabling rapid upgrading along the value chain.

The fourth policy lever has been trade and integration into global value chains. Across the 1990s and 2000s, Taiwan sought deeper integration into globalised markets by progressively opening its economy,[6] including through bilateral trade initiatives and closer cross-strait economic ties with mainland China. This outward orientation expanded access to major export markets and allowed competitive firms to scale production, attract investment, and reinvest in innovation.

At the firm level, Taiwan’s semiconductor champions actively positioned themselves within international customer networks and supply chains, ensuring that they remained embedded in the most dynamic segments of global production. Public authorities – particularly ITRI – also supported global value chain integration by linking SMEs with large foreign corporations and helping them become reliable value chain suppliers.[7] These efforts were reinforced through the promotion of strong IP practices (patents, trademarks, and portfolio-building) which reduced barriers to entry into higher-value activities and enabled participation in more sophisticated global production networks.

The fifth and last policy strategy has been diversification and the promotion of technological spillover. From the 1990s onwards, Taiwan sought to diffuse knowledge beyond core anchor industries by using public research institutions and established firms.[8] This included the diffusion of know-how and IP tools, the stimulation of spinoffs intended to generate economy-wide spillovers, and the extension of semiconductor-derived competences into adjacent sectors, such as IC design, solar photovoltaics, LEDs, and medical devices.

More recently, successive Taiwanese governments have launched a series of flagship, multi-sector innovation programmes to strengthen national competitiveness and drive innovation-led industrial development beyond the chip industry. The “5+2 Industrial Innovation Plan” and the “Six Core Strategic Industries” under the former Tsai administration,[9] followed by the “Five Trusted Industry Sectors” under the current Lai administration, collectively reflect this push to broaden Taiwan’s technological base towards other advanced fields,[10] including cybersecurity, green technologies, AI, medical and precision health, defence, and next-generation communications.

4.2 What Europe Can (and Cannot) Learn from Taiwan

While Taiwan’s meteoric rise is often compressed into a single narrative, the more relevant lesson for European policymakers is not that Taiwan simply “picked chips and won”. It is that Taiwan built an ecosystem able to industrialise innovation quickly, reliably, and continuously. In other words, Taiwan’s success is not merely a sectoral story, but a policy and capabilities story – one that combines strategic direction-setting with private-sector dynamism, cluster formation, talent policy, and deep integration into global value chains.

Some aspects of Taiwan’s experience are not readily transferable to the EU, or are closely tied to Taiwan-specific conditions. The scale and centrality of a single firm, or even a single sector, is rarely feasible, and mostly not politically desirable, in Europe. The EU’s internal market is far larger and more diversified, while its political economy makes national champions of TSMC scale structurally harder to build, and in many cases ill-advised to pursue. Another distinctive feature is Taiwan’s unique mix of geopolitical exposure and global indispensability. Europe also faces strategic dependencies and hosts globally critical industries, but not in a way that is directly comparable to Taiwan.

Yet if we separate Taiwan’s success from its most exceptional, context-specific features, a set of core lessons still stands out – lessons Europe can draw on for inspiration and adaptation. First, Taiwan shows that industrial policy works best when it shifts over time from “state-led creation” to “state-enabled upgrading”. From the outset, Taiwan’s ITRI acted less as a permanent state substitute for private innovation and more as a bridge: acquiring foreign technology, developing it to pre-commercial stages, training engineers, and spinning off commercially scalable ventures.

Taiwan’s early phases still relied on strong coordination and public institution-building, an approach that will feel familiar to European policymakers. But from the 1990s onwards, the model evolved into a system where government increasingly acted as an enabler of private-sector R&D, using horizontal tools, clearer legal frameworks for innovation policy, and instruments such as IP support mechanisms, patent pools, and venture capital platforms.

For Europe – where private-sector R&D is comparatively weak and where the default policy reflex remains direct grants[11] – the lesson is that subsidies alone are not a strategy. Industrial policy must focus on sustaining a long-run innovation pipeline, ensuring continuity from research through experimental development, and building institutions that systematically reduce the frictions that prevent scaling.

A second takeaway is Taiwan’s focus on clusters as industrial coordination mechanisms. Hsinchu Science Park, Central Taiwan Science Park, and Southern Taiwan Science Park do not merely co-locate high-tech firms: they bring together specialised suppliers, skilled labour, and frontier R&D activity in a way that generates powerful agglomeration effects and accelerated learning. In Europe, cluster strategies certainly exist, but many remain fragmented across regions, funding instruments, and short time horizons.

Taiwan’s example points to the advantages of concentrated, high-density innovation zones that are designed around the full needs of industrial upgrading: talent pipelines, supplier ecosystems, advanced testing capacity, and close industry–university linkages. This matters for Europe in particular, as emerging growth-driving technologies, quantum among them, are unusually dependent on clustering effects.[12]

Lastly, a further lesson for Europe is Taiwan’s sustained focus on talent and human capital. Taiwan has benefited from specific historical circumstances, including a long-standing pattern of returnees from abroad – something not entirely unlike Europe’s current efforts to attract talent from the US following Trump’s return.[13] Yet Taiwan’s real achievement lies elsewhere: in a structural approach that is far less dependent on context. Taiwan’s talent policy has been systemic, linking education, research, migration, and industry demand, rather than relying on small-scale “skills initiatives” detached from the production base.

Since the late 1990s, Taiwan has rolled out a series of policy initiatives explicitly aimed at building domestic human capital, particularly in science, technology, research, and the advanced workforce. It is therefore unsurprising that Taiwan now ranks at a human capital development level on a par with Sweden’s.[14] And given that Europe’s productivity challenge is, to a significant extent, the result of missing the digital revolution, the implication is clear: expanding interdisciplinary digital capabilities and strengthening advanced training systems – the backbone of Taiwan’s strategy – should be central to Europe’s own agenda.

In short, Taiwan offers Europe a model of industrial strategy, not a one-off semiconductor miracle. The EU cannot, and should not, attempt to replicate Taiwan’s unique industrial concentration or its geopolitical urgency. But it can replicate the underlying architecture: a public policy framework that turns private R&D into a sustained engine of national upgrading, cluster-based scaling and a structural approach to talent development. The central lesson is that competitiveness is not bought through subsidies alone – it is built through ecosystems that consistently convert technological potential into globally scalable production.

[1] Yuan, C. W. (2025, January 24). Taiwan’s industrial policy after the 2024 presidential election. ProMarket. https://www.promarket.org/2025/01/24/taiwans-industrial-policy-after-the-2024-presidential-election/

[2] Wong, C. Y. (2022). Experimental Learning, Inclusive Growth and Industrialised Economies in Asia. Springer Books.

[3] Ibid

[4] Global Taiwan Institute. (2025). The legacy of Tsai Ing-wen’s technology policies: The two flagship plans. Global Taiwan Brief, 10(19). https://globaltaiwan.org/2025/10/the-legacy-of-tsai-ing-wens-technology-policies/

[5] NSTC. (2024). R&D Expenditure of Science Parks by Industry and Type of Costs, and R&D Expenditure of Science Parks and Type of R&D. Available at: https://wsts.nstc.gov.tw/stsweb/technology/TechnologyDataIndex.aspx?language=E

[6] Yuan, C. W. (2025, January 24). Taiwan’s industrial policy after the 2024 presidential election. ProMarket. https://www.promarket.org/2025/01/24/taiwans-industrial-policy-after-the-2024-presidential-election/

[7] Wong, C. Y. (2022). Experimental Learning, Inclusive Growth and Industrialised Economies in Asia. Springer Books.

[8] Ibid

[9] Global Taiwan Institute. (2025). The legacy of Tsai Ing-wen’s technology policies: The two flagship plans. Global Taiwan Brief, 10(19). https://globaltaiwan.org/2025/10/the-legacy-of-tsai-ing-wens-technology-policies/

[10] National Development Council. (2024). Five Trusted Industry Sectors. Available at: https://english.ey.gov.tw/News3/9E5540D592A5FECD/52616955-2e61-4a30-95b0-1fd59c010933

[11] Dugo, A., & Erixon, F., and Abidi, I. (2025). The 8 percent approach: A big bang in resources and capacity for Europe’s economy and defence. ECIPE Occasional Papers. https://ecipe.maintenance-02-monocode.site/publications/big-bang-resources-capacity-eu-economy-defence/; and Dugo, A., Erixon, F., & Guinea, O. (2025). Models of industrial policy: Driving innovation and economic growth. ECIPE Occasional Papers. https://ecipe.maintenance-02-monocode.site/publications/models-of-industrial-policy/

[12] Erixon, F., Dugo, A., Pandya, D., & Sisto, E. (2025). Quantum clusters: Ranking the world’s deep-tech epicentres. ECIPE Occasional Papers. https://ecipe.maintenance-02-monocode.site/publications/quantum-clusters-ranking-deep-tech-epicentres/

[13] Hernández-Morales, A., Peseckytė, G., & Haeck, P. (2025, April 4). Europe to burned American scientists: We’ll take you in. Politico. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-exploit-dunald-trump-brain-drain-academic-research-progressive-institutions/

[14] Groningen Growth and Development Centre. (2023). Human capital index. https://pwt-data-tool.streamlit.app/?page=Thematic+select&countries=All&variables=hc&years=2023

References

Chang, J. C.-C., & Chiu, Y.-N. (2025, November 17). Beyond competition in the AI era: Taiwan–Korea semiconductor cooperation. Korea on Point. Available at: https://koreaonpoint.org/articles/article_detail.php?idx=492

CompaniesMarketCap. CompaniesMarketCap. Available at: https://companiesmarketcap.com/

CSIS. (2022). Why Taiwan Matters – From an Economic Perspective. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/why-taiwan-matters-economic-perspective

Cytera, C. (2024, February 12). Taiwanese Tech is More Than Semiconductors. CEPA. Available at: https://cepa.org/article/taiwanese-tech-is-more-than-semiconductors/

Dugo, A. (2024). South Korea versus Japan: What can the EU learn from the two countries? ECIPE Insights. Available at: https://ecipe.maintenance-02-monocode.site/insights/south-korea-versus-japan-what-can-the-eu-learn-from-the-two-countries/

Dugo, A. (2024). Sweden vs Switzerland: A heavyweight champions fight on innovation. ECIPE Insights. Available at: https://ecipe.maintenance-02-monocode.site/insights/sweden-vs-switzerland-a-heavyweight-champions-fight-on-innovation/

Dugo, A., & Erixon, F., and Abidi, I. (2025). The 8 percent approach: A big bang in resources and capacity for Europe’s economy and defence. ECIPE Occasional Papers. https://ecipe.maintenance-02-monocode.site/publications/big-bang-resources-capacity-eu-economy-defence/;

Dugo, A., Erixon, F., & Guinea, O. (2025). Models of industrial policy: Driving innovation and economic growth. ECIPE Occasional Papers. https://ecipe.maintenance-02-monocode.site/publications/models-of-industrial-policy/

Erixon, F., Dugo, A., Pandya, D., & Sisto, E. (2025). Quantum clusters: Ranking the world’s deep-tech epicentres. ECIPE Occasional Papers. https://ecipe.maintenance-02-monocode.site/publications/quantum-clusters-ranking-deep-tech-epicentres/

Eurostat. R&D Expenditure. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=R%26D_expenditure

Fang, T.-C. (2023, November 21). Taiwan’s top computer maker to produce servers in US to tap AI boom. Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/07fc44a3-873a-4cc0-91f4-5918b3bbe469

Global Taiwan Institute. (2025). Taiwan’s shortage of chipmakers: A major threat to the industry’s long-term growth. Global Taiwan Brief, 10(5). https://globaltaiwan.org/2025/03/taiwans-shortage-of-chipmakers-a-major-threat-to-the-industrys-long-term-growth/

Global Taiwan Institute. (2025). The legacy of Tsai Ing-wen’s technology policies: The two flagship plans. Global Taiwan Brief, 10(19). https://globaltaiwan.org/2025/10/the-legacy-of-tsai-ing-wens-technology-policies/

Groningen Growth and Development Centre. (2023). Human capital index. https://pwt-data-tool.streamlit.app/?page=Thematic+select&countries=All&variables=hc&years=2023

Hernández-Morales, A., Peseckytė, G., & Haeck, P. (2025, April 4). Europe to burned American scientists: We’ll take you in. Politico. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-exploit-dunald-trump-brain-drain-academic-research-progressive-institutions/

IMF. World Economic Outlook Database – The World Economic Outlook (WEO) Database April 1999. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/publications/weo/weo-database/1999/april

ITA. (2025). Semiconductors including chip design for AI. Available at: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/taiwan-semiconductors-including-chip-design-ai

Kennedy, P. (2025). Why Taiwan fears ‘America First’ risks eroding its ‘silicon shield’. Stimson Center. Available at: https://www.stimson.org/2025/why-taiwan-fears-america-first-risks-eroding-its-silicon-shield/

Li, L., & Fang, T.-C. (2023, May 31). How Taiwan became the indispensable economy. Financial Times. Available at: https://ig.ft.com/taiwan-economy/

McCartney, M. (2025, December 23). Asia’s economies ranked after Taiwan overtakes South Korea. Newsweek. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/asias-economies-ranked-after-taiwan-overtakes-south-korea-11258065

Motor Finance. (2025, March 5). Germany’s auto sector faces structural shifts as sales decline. Available at: https://www.motorfinanceonline.com/features/germanys-auto-sector-faces-structural-shifts-as-sales-decline/

National Development Council. (2024). Five Trusted Industry Sectors. Available at: https://english.ey.gov.tw/News3/9E5540D592A5FECD/52616955-2e61-4a30-95b0-1fd59c010933

Neufeld, D. (2025, April 17). Technology ranked: Countries investing the most in R&D. Visual Capitalist. https://www.visualcapitalist.com/rd-investment-by-country/

National Statistics, Taiwan. National statistics database. https://nstatdb.dgbas.gov.tw/dgbasall/webMain.aspx?k=engmain

NSTC. (2024). R&D Expenditure by Type of R&D. Available at: https://wsts.nstc.gov.tw/stsweb/technology/TechnologyDataIndex.aspx?language=E

NSTC. (2024). Business Enterprise R&D Expenditure by Feld of Research and Development (FORD). Available at: https://wsts.nstc.gov.tw/stsweb/technology/TechnologyDataIndex.aspx?language=E

NSTC. (2024). R&D Expenditure of Science Parks by Industry and Type of Costs, and R&D Expenditure of Science Parks and Type of R&D. Available at: https://wsts.nstc.gov.tw/stsweb/technology/TechnologyDataIndex.aspx?language=E

National Science and Technology Council. Statistics database. Available at: https://wsts.nstc.gov.tw/stsweb/technology/TechnologyStatisticsList.aspx?language=E

Reinsch, A. W., & Whitney, J. (2025). Silicon island: Assessing Taiwan’s importance to U.S. economic growth and security. CSIS. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/silicon-island-assessing-taiwans-importance-us-economic-growth-and-security

Statista. (2025, November 28). Tech GDP as a percent of total GDP in the U.S. 2017–2023. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1239480/united-states-leading-states-by-tech-contribution-to-gross-product/

Tinn, H. (2025). Island Tinkerers: Innovation and Transformation in the Making of Taiwan’s Computing Industry. MIT Press.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. Consolidated financial statements. Available at: https://investor.tsmc.com/english/financial-reports

TWSE. Available at: https://www.twse.com.tw/en/

World Bank. GDP per capita (constant 2015 US$). Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD

Wong, C. Y. (2022). Experimental Learning, Inclusive Growth and Industrialised Economies in Asia. Springer Books.

Yuan, C. W. (2025, January 24). Taiwan’s industrial policy after the 2024 presidential election. ProMarket. https://www.promarket.org/2025/01/24/taiwans-industrial-policy-after-the-2024-presidential-election/