Published

Challenges and Opportunities: Why Albania’s Accession Is Also a Strategic Choice for the EU

By: Philipp Lamprecht Bernd Christoph Ströhm

Research Areas: EU Single Market, Institutions, and Governance Trade, Globalisation and Security

Since 2009, when Albania submitted its application for EU accession to the European Council, the country has continued its gradual rapprochement with the EU. Despite economic hardships and the country’s complicated economic history, it officially achieved EU candidate status in 2014 and, next to Montenegro, is currently seen as one of the most likely Western Balkan countries to join the EU. The country is classified as an upper middle-income nation with vast potential in industries such as tourism, oil and mining, healthcare, and information technology. Albania made, without a doubt, substantial progress in macroeconomic stabilisation, improving infrastructure, and implementing EU-compatible reforms. But what are the key challenges still inhibiting EU accession?

A Tumultuous History

Albania’s political trajectory in view of EU integration is beyond a doubt influenced by its multifaceted history of the tumultuous 1980s. The traces of Enver Hoxha’s regime, who ruled over Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985, were still seen throughout the 1990s and the 2000s. Hoxha forced Albania into a rigid Stalinist economic model, characterised by extreme centralisation, collectivisation and a total state ownership of industry. In retrospect, through the lens of history, one can wonder how Albania achieved a peaceful transition from an economically isolated society into a liberal democracy. It should be also kept in mind that Hoxha’s Albania was not only isolated to Western countries, but also to other communist states, particularly after Hoxha broke ties with the Soviet Union in 1961 and later China in 1978.

Hoxha’s regime left Albania with a deeply centralised economy, underdeveloped infrastructure, and limited foreign trade options. There was a direct impact for the country’s medium-term development: economic stagnation, severe shortages of consumer goods, and a largely subsistence-based agricultural sector. Nevertheless, after Hoxha’s death and the inevitable collapse of his communist regime in 1990, Albania managed to transition to a market economy. The 1990s were however marked by economic hardships for the country – as was seen owing to hyperinflation, privatisation efforts, and a rather chaotic financial environment. A notorious episode in Albania’s multifaceted post-Hoxha economic history was the 1997 collapse of widespread pyramid schemes, wiping out savings of a large portion of the population and triggering civil unrest. The aftermath of the collapse was severe, with some 2,000 people losing their lives owing to violence. Albania sank into chaos as much of the country was no longer controlled by the government. As customs posts and tax offices were torched, government revenues plummeted, several industries halted manufacturing, and commerce was disrupted. The tumultuous period of the 1990s showed that the economic liberalisation of Albania was uneven at best. In addition, governance challenges contributed to the persistence of a large informal economy in the country.

The Dark Side of Albania’s Economy

Albania has had one of the largest shadow economies in Europe, which includes unreported employment, undeclared income, smuggling, and informal trade – in 2023, some estimates stated that Albania’s informal economy alone constituted 31,9% of its GDP, representing some USD18 billion based on GDP purchasing power parity. First and foremost, tax evasion and unregistered business operations are a factor – those issues thrive due to weak regulatory enforcement, which is driven by limited institutional capacity and corruption. The historical legacy of the country also has an impact: the sudden shift from a state-controlled to a market-based economy created gaps in governance and economic regulation, leading many activities to go underground. Moreover, sectors like construction, agriculture, and small-scale trade that are cash-based are especially vulnerable to informal practices because they depend on cash transactions. Note that the Albanian government introduced policies to tackle the issue of the country’s shadow economy, including a strategy in 2020 which aimed to grant an amnesty to businesses that have not reported funds or have made illegal profits for a fee.

One concern that persists: construction projects are often funded with “black money.” This arises from a combination of lax oversight in real estate development, widespread cash transactions, and a culture of tax avoidance. High-value construction projects, including residential and commercial real estate, may involve funds from informal channels, such as remittances from abroad that are not fully declared. The Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime also published a report in 2020, stating that construction in particular was a vital sector for money laundering in Albania. The report further outlined that out of 141 companies given building permits for high-rises between 2017 and 2019, 59% had actually no financial capacity to complete them.

Albania also faces additional considerable challenges, including persistent problems in the public sector and judiciary, along with worries tied to organised crime. The outflow of young, skilled workers (“brain drain”), worsening labour shortages is another issue, which in turn hinders investment in various sectors. Other weaknesses for Albania’s economy include inadequate infrastructure, a lack of economic diversification, a strong dependence on remittances from overseas workers, and vulnerability to potential spillover effects from economic crises in the Eurozone.

Reform Achievements and Challenges

However, much has been achieved. Albania made progress in implementing its reform and growth agenda under the so called EU growth plan for the Western Balkans by fulfilling 21 reform measures between December 2024 and June 2025. Albania has also achieved some milestones regarding judicial reform, including the government’s completion of a vetting process for judges and prosecutors. These developments are vital steps for meeting the EU accession requirements of Chapter 23, namely Rule of Law. In November 2025, the European Commission adopted its annual Enlargement package and outlined progress made by the EU’s enlargement partners. It concluded that Albania made considerable progress regarding EU accession in 2025, having opened four EU clusters. The Commission further outlined that Albania indeed achieved advancements regarding EU accession fundamentals, in relation to justice reform and combating organised crime and corruption.

In the light of those developments, Albania’s Prime Minister Rama is sticking to the target of 2027 for completing EU accessions negotiations on all 33 negotiating chapters. The full membership of Albania is expected to be facilitated by 2030 as part of Rama’s plans.

Nevertheless, despite this progress, the long-term resilience of Albania’s judicial system is still undermined by ongoing political interference and a lack of operational coordination between governing bodies. Although a structure for judicial reform is in place, its execution is still somewhat incomplete and lacks coherence. Albania’s battle against its corrupt judicial system has also resulted in a significant shortage of judges.

Albania’s Interconnectedness and Strategic Ties are Strong

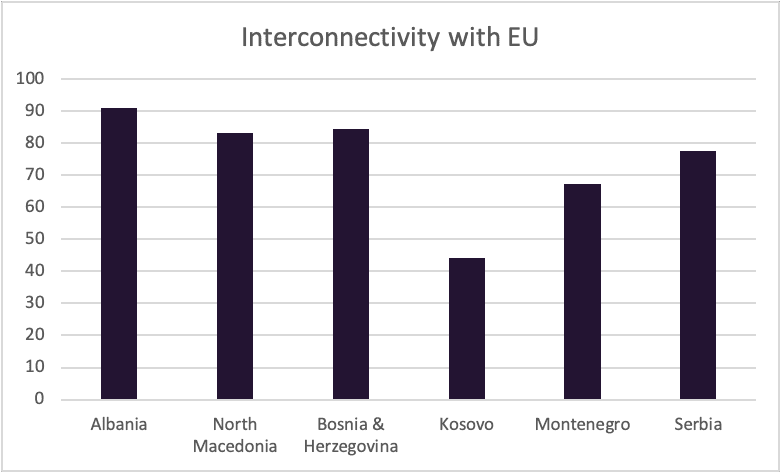

It is important to also consider the bigger geopolitical picture for the EU. Regarding interconnectedness with the EU, it is evident that Albania is the most EU-interconnected country in the Western Balkans. In 2023, Albania holds the highest overall GEOII score[1] with the EU in the Western Balkans, ahead of Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia.[2] This dominant EU position reflects Albania’s close integration in trade, policy alignment, low tariff barriers and regulatory similarities common to the Western Balkans sub-region, which the index highlights as the EU’s most policy-interconnected neighbourhood (especially regarding Non-Tariff Measures, fiscal and monetary policy alignment, and data regulation frameworks). It has to be stressed that the Western Balkans’ interconnectedness with the EU in general has been remarkably stable over the past decade, with just minor occasional fluctuations. The region is far more closely interconnected with the EU than with the US, China or Russia.

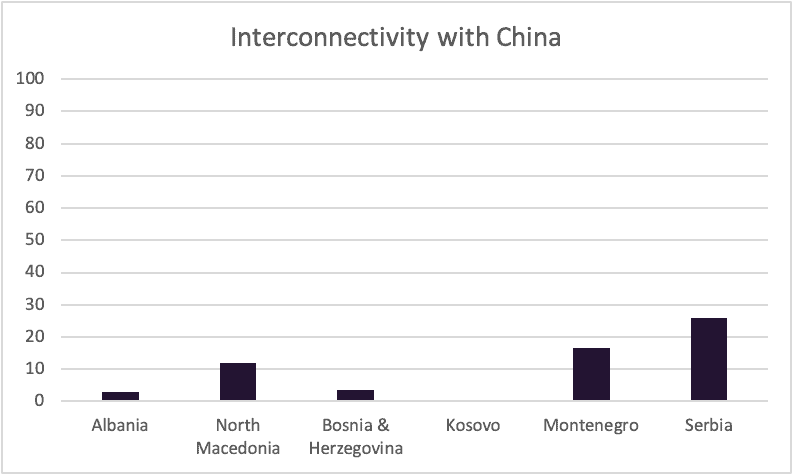

China has emerged as the second most interconnected power with the Western Balkans, driven mainly by the stronger linkages between China and Serbia. However, despite this rise of China in the region, Albania has the strongest interconnectedness with the EU and only has a relatively low degree of interconnectedness with China (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Albania remains the most interconnected Western Balkan country with the EU (from 0 – least interconnected, to 100 – most interdependent)

Figure 2: Albania only has a low interconnectedness with China (from 0 – least interconnected, to 100 – most interdependent)

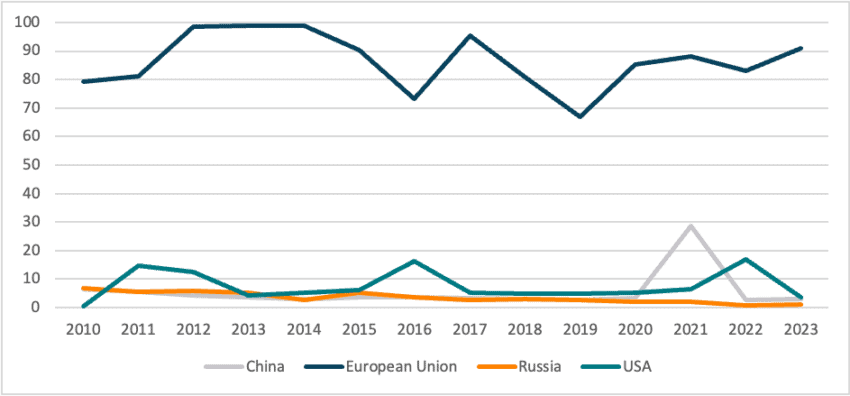

Albania’s strong interconnectedness with the EU across the board of the three pillars of the GEOII – economic, financial and policy interconnectedness – has remained stable since 2010 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Albania’s strong interconnectedness with the EU has remained since 2010 (from 0 – least interconnected, to 100 – most interdependent) Note: Figure 3 displays the overall interconnectedness of Albania to the EU (yellow), China (red), the US (blue) and Russia (black) from 2010 to 2023. The interconnectivity is measured as the combined GEOII score, including all pillars of economic, finance and policy interconnectedness combined.

Note: Figure 3 displays the overall interconnectedness of Albania to the EU (yellow), China (red), the US (blue) and Russia (black) from 2010 to 2023. The interconnectivity is measured as the combined GEOII score, including all pillars of economic, finance and policy interconnectedness combined.

As for the economic influence of China, it has emerged as Albania’s second most significant partner for trade in goods, though it trails well behind the EU, with Italy being the most important trading partner with 27.8% of total trade. While the occurrence of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Western Balkan countries has been rising since the Belt and Road Initiative was launched in 2013, Chinese FDI is still absent in Albania.

Albania and the EU: Next Steps

The key question regarding Albania’s EU accession aspiration is whether the country itself can be regarded as a “low-hanging fruit”, and whether the EU and Albania should both focus on the easiest, most accessible tasks for EU accession. It should be emphasised, that the country can indeed be considered a low-hanging fruit because of its potential as a relatively small and accessible market for investment and business, its strong interconnectedness with the EU, a government actively seeking foreign investment, and a young population eager to work. This was also recognised by the EU itself. It is beyond doubt that Albania’s EU accession itself is in the EU’s own strategic interest, and that there is a currently a strong pro-EU momentum in the country. However, in light of this positive momentum, the Albanian government is now called upon not to lose sight of addressing basic issues that may get in the way of proper EU accession – namely systemic problems in its judiciary and corruption.

In terms of policy conclusions, it becomes clear that Albania has been and remains a strong partner country in the region for the EU. In light of this development, the EU should accelerate accession negotiations while also considering policy collaboration with regards to raw materials resilience. The EU should in addition consider signing strategic agreements with key neighbours such as Albania for critical raw materials (CRMs). Finally, it should provide EU-funded technical assistance to support compliance with environmental, social and governance standards under the Critical Raw Materials Act.

It should be stressed that Albania is willing to join the EU. Therefore, it is now important that the EU further supports the country in its endeavours and that EU member states themselves do not repeat the same errors made in North Macedonia, where momentum for EU accession has been lost over the last six years. While Albania is often referred to as a “low-hanging fruit” regarding accession, this does not capture the full picture. Much is at stake and the EU has a lot to lose too. Albania’s accession should also be seen in a geopolitical and strategic policy context by EU officials – and the window of opportunity for a strong partnership leading towards accession is now.

[1] The Geoeconomic Interconnectivity Index (GEOII) measures interconnectivity through values with a range from 0 (least interconnected) to 100 (most interdependent).

[2] The Geoeconomic Interconnectivity Index (GEOII) quantifies the relative strength of the EU’s trade, financial and policy relationships with 21 EU neighbouring countries including the Western Balkans, its Eastern neighbours, Türkiye and the Southern Neighbourhood. Drawing on 43 indicators, it offers a comparative, data-driven assessment of the EU’s geoeconomic footprint between 2010 and 2023. The GEOII is structured across three sub-dimensions: Trade interconnectivity, Financial interconnectivity, and Policy interconnectivity. See: https://geoii.eu/start

Annex: Overview of GEOII

The Geoeconomic Interconnectivity Index (GEOII) quantifies the relative strength of the EU’s trade, financial and policy relationships with 21 countries including the Western Balkans, its Eastern neighbours, Türkiye and the Southern Neighbourhood. Drawing on 43 indicators, it offers a comparative, data-driven assessment of the EU’s geoeconomic footprint between 2010 and 2023. The index measures interconnectivity in values from 0 (least interconnected) to 100 (most interdependent). The GEOII is structured across three sub-dimensions:

Trade interconnectivity, capturing flows of goods, services and digital trade – arguably the cornerstone of the EU’s external influence. It reflects the EU’s ambition to balance open strategic autonomy with the resilience of supply chains and sustainability goals.

Financial interconnectivity, measuring foreign direct investment (FDI), external debt, direct budgetary support, bank lending and the euro’s regional role. These are also key instruments of the EU’s economic diplomacy.

Policy interconnectivity, covering trade and investment agreements, regulatory alignment, monetary and fiscal convergence, sanctions and arms transfers. This dimension assesses the depth of institutional integration and alignment.