Published

Europe’s Real Trade Weapon Is Not Tariffs on Goods

Research Areas: EU Single Market, Institutions, and Governance North America Trade, Globalisation and Security

Over the weekend, President Donald Trump’s anger at Europe flared once again. The United States announced its intention to impose a 10 per cent tariff from 1 February on products from eight European countries, citing the ongoing dispute over Greenland. Among the affected EU member states are Germany, the Netherlands, France and Denmark.

The central question now is how the European Union should respond. Ideally, it would do so wisely. The first-best option remains diplomatic. Nobody benefits from a trade war. It inflicts economic pain on both sides of the Atlantic, disrupts supply chains and risks escalating political tensions that are already difficult to contain.

If, however, the EU concludes that it cannot leave this move unanswered, the question becomes how to respond. A second-best solution would be a targeted and intelligible one, designed to exert maximum political and economic pressure on the United States while minimising collateral damage to European consumers and businesses.

To apply meaningful pressure, the EU needs leverage. The €93 billion retaliatory tariff package currently on the table, should President Trump follow through, would provide some. It targets prominent American interests, including companies such as Boeing, as well as politically sensitive exports such as bourbon and soybeans.

Yet the United States’ real point of economic vulnerability lies elsewhere. The greatest potential pain is not in goods, but in services. Services are precisely where American firms are most dependent on access to the European market.

Europe exports a wide range of industrial and consumer products to the United States, and tariffs on these goods ultimately hurt European producers. By contrast, American firms stand to lose far more if their access to the European market is restricted in sectors where they export significantly more than they import. This asymmetry is most pronounced in services.

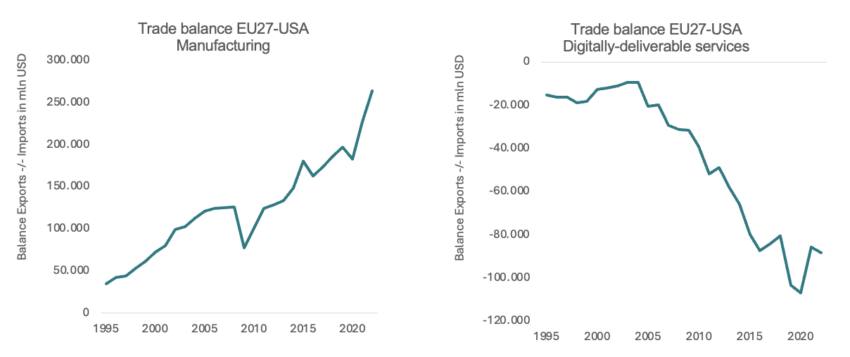

It is particularly evident in digitally deliverable services, which include management consulting, finance and insurance, cloud services, business processing, professional services and marketing. In these areas, the United States enjoys a large and growing trade surplus with the EU.

Just as many of President Trump’s tariffs target sectors in which the United States runs a trade deficit, the EU could mirror that logic. In services, especially digitally deliverable ones, Europe runs a substantial deficit. These are precisely the markets American firms are most eager to access. (Figure 1, right-panel)

Figure1: EU has a trade surplus with the US in goods, but a deficit in services. Source: own computations using OECD.

Source: own computations using OECD.

Services also offer the EU an advantage that goods tariffs lack, namely speed. Adjusting tariff schedules takes time, and their economic impact may come too late to influence political decision-making. By contrast, many services are delivered online and can be restricted almost instantaneously, allowing the EU to act quickly and decisively.

Rather than focusing retaliation on goods such as aircraft, where the United States already imports more from Europe than it exports, the EU should therefore concentrate on services, where European leverage is strongest.

Crucially, the EU already has the legal tools to do so. Its Anti-Coercion Instrument allows the Union to respond to economic pressure from third countries with targeted countermeasures, including restrictions on services and investment. It provides a credible framework for acting beyond traditional goods tariffs, should diplomacy fail.

Critics will argue, rightly, that taxing digital and technology-related services risks harming European firms that rely on advanced technologies. There is no European equivalent to Microsoft, no continental substitute for Amazon’s cloud infrastructure and no second European Netflix.

But this objection should not be overstated. The EU’s services deficit does not only reflect dependence on core digital platforms. It also spans a wide range of digitally enabled business services for which European alternatives are readily available. Europe may not be a technology champion, but it remains a services powerhouse.

Management consulting, legal and accounting services, architecture and engineering, and parts of financial services are all increasingly delivered digitally, and in these fields Europe has strong domestic providers. Firms can turn to Roland Berger rather than Boston Consulting Group, or to Capgemini instead of Accenture. European financial institutions are equally capable of filling many roles currently dominated by American firms.

Crucially, Europe already exports these services successfully to the rest of the world, running a surplus outside the United States. That record demonstrates Europe’s global competitiveness in these sectors. Replacing imported American services in these areas would therefore not be prohibitively difficult.

If the EU must retaliate, it should do so strategically. Services, not goods, are where American dependence on Europe is greatest, European leverage is strongest, and the political signal would be clearest.