Published

The Legality of Trump’s IEEPA Tariffs: What Can the EU Expect from the SCOTUS Decision?

By: Renata Zilli

Research Areas: North America Trade, Globalisation and Security

A decision by the US Supreme Court on the “Liberation Day Tariffs” is expected soon. More precisely, the decision concerns the legality of President Trump’s use of the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) to impose tariffs. Since the announcement of “Liberation Day Tariffs” on April 2nd last year, President Trump has signed a series of policy frameworks and economic and trade agreements with more than a dozen countries. Several of these agreements are not legally binding. For those in force, their legal effect derives from U.S. law – specifically, the national emergency under IEEPA, which is now challenged before the Supreme Court.

The case raises many questions. Chief among them is whether the US can continue with the Liberation Day tax on imports. If the Court decides that the tariffs are unlawful, they cannot continue, and most likely, it would allow importers who paid duties under IEEPA to seek refunds. Following the first oral arguments, more than 1,000 firms have joined tariff suits. Some estimates suggest that refunds could reach as much as USD 150 billion.

The fiscal dimension is important. Revenue from tariffs is projected to increase federal revenue in 2027 by USD 142.9 billion, or 0.4 per cent of US GDP. If IEEPA tariffs are rejected, however, the same estimates suggest that tariff revenue would amount to only around 0.12 per cent of GDP. The One Big Beautiful Bill (BBB), signed into law, is projected to add USD 3.4 trillion to the US fiscal deficit over the next decade. While the Bill focuses on tax reductions, the Trump administration established that tariffs were the fiscal offset. If IEEPA tariffs are deemed unlawful, the hole in US public finances will grow bigger, and the government will be pushed to raise revenues, potentially using other tariffs, to stabilise its fiscal position.

While previous US presidents have been granted authority by Congress to impose tariffs in contingency situations – a point the Trump administration has invoked in its defence, none have relied on IEEPA to declare the US trade deficit a national emergency. Notably, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit observed that, under IEEPA, Congress did not delegate to the President the authority to impose tariffs. The Supreme Court may, however, add a wrinkle by separating the two states of emergency declared by the Administration: one related to the trade deficit and the other to the opioid crisis.

The result may be a partial rejection rather than a wholesale validation or rejection of all the emergency tariffs. In particular, the Court may uphold the fentanyl-related emergency while rejecting the trade-deficit rationale. In practice, this would mean that tariffs collected on imports from China, Canada, and Mexico (non-USMCA-compliant) would remain valid, while the emergency tariffs on most other countries would be illegal.

For the EU and the rest of the world, this scenario would be no less concerning, as it could establish a legal basis for emergency tariffs on China. In recent days, China announced that its trade surplus reached USD 1.19 trillion, an increase of 20 per cent from 2024, indicating that it is maintaining its strategy of boosting exports to global markets despite US tariffs. While there are different implications for the global economy if US reciprocal tariffs remain valid, one political effect of China’s persistent trade surplus for the rest of the world is that the US will exert greater pressure on its partners and allies to toughen or mimic their trade policy towards China.

Although “Liberation Day” tariff rates varied across countries, a uniform 10 per cent tariff was applied across the board. As a result, any company that imported goods into the US in 2025 is likely to have paid IEEPA duties. Alongside the emergency tariffs, other sectoral tariffs remain in place, covering steel, aluminium, copper, wood and lumber, as well as automobiles. Most of these measures are grounded in statutory authority, particularly Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which empowers the president to impose tariffs – a hallmark of Trump’s first-term trade policy.

One lesson from Trump’s first term appears to have been fully grasped: the speed of the US political cycle. Therefore, a key distinction between relying on statutory authority, such as the Trade Expansion Act, lies in timing. Section 232 investigations can take between 100 and 150 days. IEEPA, by contrast, allows the President to act almost immediately. By using emergency motivations, Trump won time and leverage.

What Happens After a Ruling Against IEEPA?

A Supreme Court ruling invalidating IEEPA-based tariffs would remove the administration’s ability to impose, modify, or negotiate tariffs with immediate effect, stripping trade policy of the urgency and leverage that emergency powers uniquely provide. Hence, a ruling against IEEPA would primarily affect tariffs imposed solely under emergency authority. Measures grounded in other statutes – notably Sections 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, and Section 604 of the Trade Act of – would remain in force for the goods and sectors they cover. Some of these statutes also underpin several negotiated arrangements concluded in 2025, but to varying degrees and with important legal distinctions.

A ruling against IEEPA raises two main questions. First, could existing frameworks that the Trump administration signed remain valid if the IEEPA authority is curtailed? Second, to what extent would agreed conditions remain de facto binding even if they lack a clear de jure basis? Even highly asymmetric frameworks concluded under the current administration included concessions, creating incentives for partners to preserve at least parts of the deal.

Take the case of the US–Japan Agreement. Its legal validity rests entirely on delegated presidential authorities such as IEEPA, the National Emergencies Act (NEA), Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, and Section 604 of the Trade Act of 1974. Under this agreement, Japan is shielded from higher reciprocal tariffs imposed under Executive Order 14257 (the so-called “Liberation Day Tariffs”), as its imports are subject to a maximum effective tariff rate of 15 per cent. These across-the-board tariffs remain in force only so long as IEEPA provides a legal basis.

For certain products covered by Section 232 — most notably automobiles and automobile parts — Japan’s exports are subject to a 15 per cent tariff ceiling. Although limited, this arrangement puts Japan in a more favourable position than US trading partners without any 232 concession. While the baseline Section 232 tariff on imported vehicles and auto parts is set at 25 per cent, Japan’s exports now enjoy a relative tariff advantage of up to 10 percentage points. In theory, this agreement places Japanese exporters under a more controlled and predictable tariff regime.

However, concessions made under section 232 cannot stand on their own without IEEPA. The statute allows the US president to impose trade restrictions on national security grounds, but it does not independently authorise permanent exceptions or tariff ceilings. Those outcomes require additional executive authority, which has been granted through emergency powers under the IEEPA and the National Emergencies Act. If that legal foundation were removed, the preferential treatment would have no standalone statutory basis, and the original Section 232 tariffs would reapply by default.

A similar logic applies to the US–UK Economic Prosperity Deal. Under this arrangement, the UK is shielded from the full application of Section 232 tariffs through a series of preferential measures, including a 100,000-vehicle tariff-rate quota at a combined tariff of 10 per cent, prospective MFN-rate quotas for steel and aluminium, and tariff-free treatment for certain aerospace products. Unlike Japan’s 15 per cent maximum tariff ceiling, the US-UK agreement does not establish a blanket cap on reciprocal tariffs. UK exports remain, in principle, subject to the Liberation Day framework. Crucially, these preferences derive their legal force from the underlying emergency authority rather than from Section 232 itself. In a post-IEEPA scenario, Section 232 would continue to operate, but only in its original, unilateral form. Tariffs would revert to baseline levels and could only be suspended if the President determines that the national security threat identified in the original investigation has been mitigated — not as part of a negotiated trade framework.

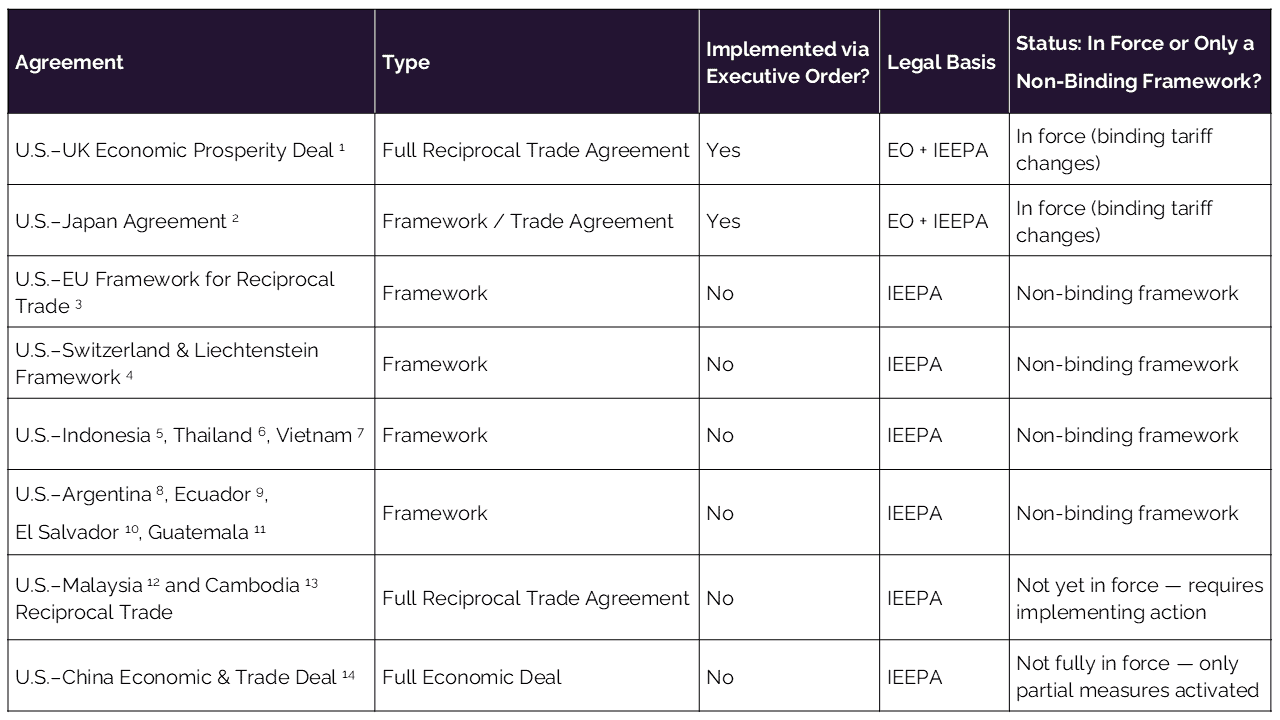

For agreements that remain at the framework level and are not yet in force (see Table 1), the administration would be unable to collect tariffs at agreed rates without congressional approval. In the absence of Trade Promotion Authority, any legislative pathway would be procedurally uncertain. Hence, a ruling against the IEEPA tariffs would significantly constrain the Trump administration’s ability to sustain negotiated tariff outcomes at agreed rates without congressional approval. Without a doubt, the White House is likely to seek alternative legal pathways to preserve a degree of legal ambiguity, maintaining room for negotiation and geopolitical pressure.

Table 1: Trade agreements and frameworks concluded under the Trump administration in 2025

Implications of the IEEPA Ruling for the EU’s Own Strategic Choices

For the EU, the significance of the IEEPA case lies in both the immediate fate of specific tariff arrangements and the EU’s security and strategic considerations. An adverse ruling on IEEPA tariffs would weaken the credibility of emergency-based tariff threats. In consequence, this would constrain the administration’s ability to extract concessions through immediate trade pressure, shifting the balance of leverage in ongoing negotiations. This is where a potential judicial invalidation of IEEPA-based tariffs becomes decisive for the EU. Recent threats to impose tariffs on some European countries over Trump’s fixation on annexing Greenland as part of the US territory reveal that trade measures will be deployed for any unexpected political purpose.

An adverse ruling on tariffs would provide the EU with a new and legitimate basis for addressing commercial policy disputes. This could be a golden opportunity to utilise established institutional mechanisms to settle commercial disputes, either by retaliating or by resorting to the EU’s trade defence mechanisms. For EU exporters, uncertainty will remain high in the short term, particularly in sectors exposed to Section 232, where tariffs are in place, such as steel, aluminium (and their derivatives), copper, autos, auto parts, and lumber. At the same time, additional Section 232 investigations are ongoing in strategically sensitive sectors, including semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, and medical supplies. This sequencing matters: by relying on IEEPA in the interim, the administration effectively gained time, ensuring that by the time emergency tariffs are legally challenged or curtailed, the outcomes of the USTR investigations may already be enforceable.

From a European perspective, this creates a difficult strategic environment, as market access will remain secured through conditional and reversible executive arrangements. Without IEEPA, trade relations would revert to a landscape shaped by unilateral, sector-specific measures grounded in statutory authority, with Section 232 once again becoming the primary instrument of trade restriction.

The current US–EU framework signed in Turnberry remains incomplete and not yet in force, leaving room for further negotiation but also prolonging uncertainty. Thus, a SCOTUS ruling against IEEPA would invalidate the US–EU framework, but it would not restore the status quo ante. Recent US threats to use tariffs in response to geopolitical disagreements further underscore how closely trade policy has become intertwined with security and foreign policy considerations, with some even suggesting the EU should decouple from the US. In a conversation, Prof. Timothy Garton Ash stated that if Europe wants to matter geopolitically, it must become a three-dimensional power – regulatory, economic and military: “strategic autonomy is not just about ideas, [economic competitiveness] but political will.” The EU must now embrace the fact that it needs to develop additional capabilities, but these must be anchored in the reality that this will take time. During that process, the EU can take advantage of this opportunity to galvanise its domestic political forces towards common objectives. On the trade front, this historical moment should encourage the EU to engage more openly with partners around the world – but from a position of greater internal coherence and strength.

1 Executive Order 14309—Implementing the General Terms of the United States of America–United Kingdom Economic Prosperity Deal | The American Presidency Project. (n.d.). https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-14309-implementing-the-general-terms-the-united-states-america-united

2 The White House. (2025, September 4). Implementing the United States–Japan Agreement. https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/09/implementing-the-united-states-japan-agreement/

3 The White House. (2025, July 28). Fact Sheet: The United States and European Union reach massive trade deal. https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/07/fact-sheet-the-united-states-and-european-union-reach-massive-trade-deal/

4 The White House. (2025, November 14). Joint Statement on a framework for a United States – Switzerland – Liechtenstein Agreement on Fair, Balanced, and Reciprocal Trade. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/11/joint-statement-on-a-framework-for-a-united-states-switzerland-liechtenstein-agreement-on-fair-balanced-and-reciprocal-trade/

5 The White House. (2025, July 22). Fact Sheet: The United States and Indonesia reach historic trade deal. https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/07/fact-sheet-the-united-states-and-indonesia-reach-historic-trade-deal/

6 The White House. (2025d, October 28). Joint Statement on a framework for a United States-Thailand Agreement on Reciprocal Trade. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/10/joint-statement-on-a-framework-for-a-united-states-thailand-agreement-on-reciprocal-trade/

7 The White House. (2025, October 28). Joint Statement on United States-Vietnam Framework for an Agreement on Reciprocal, Fair, and Balanced Trade. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/10/joint-statement-on-united-states-vietnam-framework-for-an-agreement-on-reciprocal-fair-and-balanced-trade/

8 The White House. (2025, November 13). Joint Statement on Framework for a United States-Argentina Agreement on Reciprocal Trade and Investment. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/11/joint-statement-on-framework-for-a-united-states-argentina-agreement-on-reciprocal-trade-and-investment/

9 The White House. (2025, November 13). Joint Statement on Framework for United States-Ecuador Agreement on Reciprocal Trade. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/11/joint-statement-on-framework-for-united-states-ecuador-agreement-on-reciprocal-trade/

10 The White House. (2025, November 13). Joint Statement on Framework for United States-El Salvador Agreement on Reciprocal Trade. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/11/joint-statement-on-framework-for-united-states-el-salvador-agreement-on-reciprocal-trade/

11 The White House. (2025, November 13). Joint Statement on Framework for United States-Guatemala Agreement on Reciprocal Trade. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/11/joint-statement-on-framework-for-united-states-guatemala-agreement-on-reciprocal-trade/

12 The White House. (2025, October 31). Agreement between the United States of America and Malaysia on reciprocal Trade. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/10/agreement-between-the-united-states-of-america-and-malaysia-on-reciprocal-trade/

13 The White House. (2025, October 28). Agreement Between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Cambodia on Reciprocal Trade. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/2025/10/agreement-between-the-united-states-of-america-and-the-kingdom-of-cambodia-on-reciprocal-trade/

14 The White House. (2025, November 5). Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Strikes Deal on Economic and Trade Relations with China. https://www.whitehouse.gov/fact-sheets/2025/11/fact-sheet-president-donald-j-trump-strikes-deal-on-economic-and-trade-relations-with-china/