Time is Money: The Cost of Delaying the Ratification of the EU-Mercosur Trade Agreement

Published By: Fredrik Erixon Oscar Guinea Philipp Lamprecht Elena Sisto

Research Areas: EU Single Market, Institutions, and Governance EU-Mercosur Project Latin America Trade, Globalisation and Security

Tags: EU Mercosur trade agreement

Summary

Between 2021 and 2025, the EU sacrificed €183bn in exports and €291bn in gross domestic product due to its failure to ratify the EU-Mercosur Agreement. These figures represent the net present value of economic activity that would have materialised had the agreement been implemented as originally scheduled in 2021. This accumulated nominal GDP loss, which reflects not only foregone exports but also unrealised gains from improved access to inputs and diversified supply chains, corresponds to approximately 1.6 per cent of the EU’s total economic output and is equivalent to roughly two years of nominal European economic growth at the rates observed in 2023 and 2024.

Should ratification continue to be deferred through 2026, the cumulative toll will continue to grow. Total foregone exports would reach €216bn, while lost GDP would climb to €344bn. To place this in perspective, the cumulative export loss would exceed the total annual trade of goods between the EU and Switzerland, the EU’s fourth-largest trading partner. Every additional month of delay during 2026 amounts to €4.4bn in foregone GDP and €3bn in missing exports.

The economic burden of delay is concentrated in economic sectors where the EU maintains a competitive advantage. Transport equipment faces the most severe impact, with a shortfall of €94bn in exports over the six-year delay scenario. Machinery and equipment constitute the second-largest loss category at €23.8bn, followed by chemicals at €21.2bn, iron and steel and agri-food at €12.6bn each, and pharmaceuticals at €11.5bn.

These sectors are precisely those that drive European economic dynamism. Pharmaceuticals and chemicals rank among the top five manufacturing sectors for labour productivity, while transport equipment and machinery sit in the top ten. For transport equipment, chemicals, and iron and steel, the six-year delay represents lost sales equivalent to more than two years of each sector’s annual research and development budget. The services sector has also experienced substantial forgone gains, with a five-year delay translating into €3bn in lost service exports, concentrated in trade and logistics (€1.9bn), communications (€0.6bn), and financial services (€0.4bn).

The costs of delayed ratification fall across every EU member state. Germany has had the largest absolute loss at €71bn, equivalent to 1.7 per cent of GDP, incurred during a period when the economy contracted. France experienced €38bn in foregone exports (approximately one year of nominal economic growth), while Italy lost €29bn (roughly 1.6 years of growth). Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, Sweden, Portugal, and Austria also had substantial absolute losses. While smaller, export-oriented economies have lower absolute losses, their relative exposure is significant: Portugal, Hungary, Belgium, Finland, and Sweden experienced losses exceeding 1 per cent of national GDP.

The cost of delaying the EU-Mercosur Agreement goes beyond sale losses. Faced with policy uncertainty, European firms are diverting capital and establishing supply chains that will not return to Mercosur, surrendering market share to China and eroding Europe’s influence in the region. Crucially, the delay is also detrimental to strengthening the EU’s economic resilience. By delaying the ratification of the agreement, the EU is losing preferential access to Mercosur’s vast critical raw materials. Ultimately, Europe’s hesitation prolongs its dependence on Chinese supply chains for these essential inputs.

The opportunity cost of continued delay substantially exceeds any remaining policy concerns. The political framing of delay as a cost-free option that allows for additional deliberation is inaccurate and counterproductive. The costs of postponement are real, measurable, and growing. For European policymakers, the imperative is clear: ratifying the EU-Mercosur Agreement is not merely a trade policy decision but an essential step toward strengthening Europe’s economic growth, competitiveness, and economic resilience.

Preface

At a time when protectionism and geopolitical challenges play a greater role, it is crucial for the EU to secure access to new markets whilst taking the global leadership for free, sustainable, predictable, and rules-based trade. Concluding new free trade agreements is therefore key for the global competitiveness of European businesses.

The most pressing agreement is with the Mercosur countries. After many years of negotiations, the agreement now needs to be finalised. The EU has already missed out on significant export gains and GDP growth due to the delayed implementation of the agreement since 2021. In light of this, the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise has commissioned ECIPE to calculate the costs of the delay, both in terms of export losses and GDP losses, including the effects of unrealised imports. The results speak for themselves.

It is critical that the agreement is approved and implemented swiftly to avoid further losses. The agreement will give European businesses better access to an attractive market that has traditionally been characterised by high tariffs and complex regulations – access that Chinese or American companies, for example, currently lack. It establishes long-term conditions for diversifying both imports and exports, gives businesses access to critical raw materials needed for the green and digital transition – and sends a signal to the rest of the world that Europe continues to support open and rules-based global trade rather than destructive protectionism.

Anna Stellinger, Deputy Director General, Head of International and EU Affairs

Confederation of Swedish Enterprise

1. Introduction

The European Union is finally getting closer to ratifying its trade agreement with Mercosur. In early 2026, EU member states voted to approve the agreement, and, in the next weeks and months, the European Parliament will cast its vote – hopefully an approval. As every observer of EU trade policy knows, the plan was for approval to happen years ago. The political agreement was signed already in 2019, and the expectation was that the EU would ratify it by 2021. Late last year, there was an attempt to push the agreement beyond the finishing line, but ratification was once again postponed, adding another chapter to a saga that first began in 2000. After a quarter century of talks, negotiations, and political intrigue, the deal could not be done – and powerful member states and organisations were yet again asking for “more time” and complained they have been rushed into the agreement.

There is an important lesson to be learned from the drama: the glacial pace of the EU-Mercosur trade negotiations has hurt the economy. Benjamin Franklin is said to be the source for a simple but important economic maxim: “time is money”. What we fail to achieve today, will impact us in the future. Delayed economic growth is also denied economic growth. For European businesses and consumers, the prolonged timeline for the trade agreement represents a significant economic loss. It is sometimes forgotten, it seems, that trade agreements do actually boost sales and economic activity. Hence, every day that passes without ratification translates into forgone sales, and when every day of missed opportunities is added up, it becomes a very big number of lost trade. Given that the EU economy grew by only 0.4 and 1.1 per cent in 2023 and 2024 – and only averaged an annual growth rate of 1.6 per cent between 2016 and 2024[1] – the unrealised gains from trade should not be dismissed.

The opportunity cost of delay, however, extends beyond these direct trade effects. Modern trade agreements do more than lower tariffs: they also influence where firms place production and how they organise value chains. When trade policy remains ambiguous, firms tend to reallocate resources towards jurisdictions offering greater certainty. This reorientation of supply chains away from the Mercosur countries represents a permanent loss of the EU’s competitive positioning in the region, as the delay in the ratification of the agreement postpones the critical ‘investment moment’ when firms decide whether to commit to the market.

This matters particularly in the context of Europe’s strategic supply-chain objectives. The EU-Mercosur Agreement is a key component of the EU’s strategy to diversify away from vulnerable dependence on China in critical raw materials. Moreover, the European Commission calculates that thanks to the agreement, the EU could reclaim its title as Mercosur’s leading supplier and cushion the blow of higher US tariffs by redirecting EU exports towards Mercosur.[2] This diversion would amount to nearly €3bn, a 6.2 per cent boost above the baseline gains expected from the EU-Mercosur deal. In the absence of the agreement, however, these benefits will never materialise.

This is a fundamental point. The opportunity cost of delaying the ratification of the agreement is huge. Europe’s inability to ratify the agreement is not only measured in terms of shrinking geopolitical clout but also in hard cash. This Policy Brief quantifies these forgone benefits, the unrealised exports and GDP growth since 2021 due to the ratification stalemate and the additional cost of delaying the ratification beyond 2025. It estimates how much export sales and GDP that the EU will have lost because of its inability to ratify the agreement, once it has been implemented in full.

The next chapter presents our estimates of the ‘missing trade’ resulting from the delays in ratifying the EU-Mercosur deal. It presents this ‘missing trade’ for two time periods. The first time period shows the trade foregone since the agreement-in-principle was reached, covering the period 2021-2025. The second time period projects the cost if the agreement remains unratified throughout this year (extending the period to 2021-2026) – in the event, for instance, that the European Parliament will not be willing to approve the agreement imminently. The results are broken down across economic sectors and EU countries. Chapter 3 concludes with a summary of the main findings. The Annex presents the methodology.

[1] Eurostat (2025). Gross domestic product (GDP) and main components (output, expenditure and income). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/NAMA_10_GDP

[2] European Commission (2025). Economic analysis of the negotiated outcome of the EU-Mercosur partnership agreement (EMPA). Publications Office of the European Union. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/6f1a741f-677e-11f0-bf4e-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

2. The Cost of the Delay in the Ratification of the EU-Mercosur Agreement

In June 2019, after 20 years of negotiations, the EU and Mercosur signed a political agreement that concluded the trade negotiations between the two sides. The then President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, called it “a historical moment.” Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström said that the new market access will provide “enormous opportunities for EU businesses and workers in countries with whom we have strong historical links and whose markets have been relatively closed up to now.” The Agricultural Commissioner, Phil Hogan, called it a “fair and balanced deal” with opportunities for European farmers.[1] After the summit, the agreement would go through a legal scrubbing and then be sent to the European Council and the European Parliament for ratification. By 2021, the deal would be implemented and the opportunities it created for European exporters would be there to use.

By the end of 2025, the EU-Mercosur Agreement should have been live and in operation for five years. Important for our calculation, is that the agreement includes a gradual phase-in period of up to 15 years during which tariffs and barriers are progressively reduced, meaning the economic benefits grow over time as market access expands. In other words, after five years the benefits of the agreement would have started to reach levels that mean sizeable contributions to the European economy. In this chapter we are estimating the net present value of the missing export gains in the past five years and the contribution the agreement would have made to the EU economy. The baseline estimate is for five years, assuming that the agreement would have operated for five years by close of 2025. We are also adding a 6-year scenario, estimating the costs to European exporters of another year of delayed ratification.

2.1 Aggregate Economic Impact

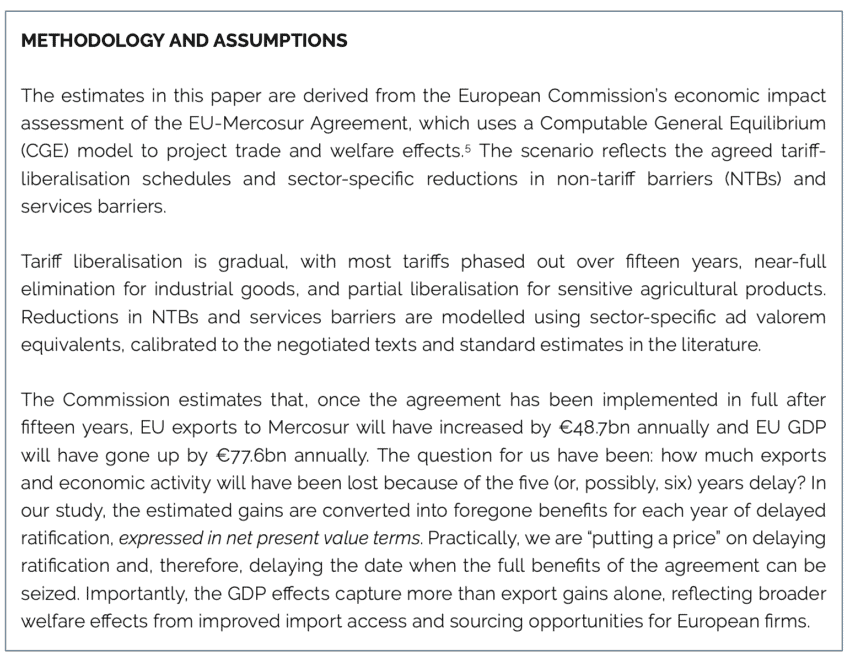

The economic costs of delaying the EU-Mercosur Agreement are the trade and economic activity forgone when the ratification of the agreement is postponed. The resulting annual losses are expressed in present-value terms: that is, future gains of the agreement are converted into today’s euros to reflect the fact that benefits received later are worth less than benefits received sooner – and then added up over time to show the total cost of delay.[2] The cost of the delay to the EU economy has been substantial. With a delay of five years for the deal to become effective, the EU has in net present value terms already forgone €183bn in exports and €291bn in GDP (see Table 1). Should ratification be delayed through 2026, total forgone exports amount to €216bn and GDP losses €344bn. To put these figures in perspective:

The cost of the delay to the EU economy has been substantial. With a delay of five years for the deal to become effective, the EU has in net present value terms already forgone €183bn in exports and €291bn in GDP (see Table 1). Should ratification be delayed through 2026, total forgone exports amount to €216bn and GDP losses €344bn. To put these figures in perspective:

- The €216bn in foregone exports exceeds the EU’s entire annual merchandise exports to Switzerland, the EU’s fourth-largest trading partner.

- The estimated €291bn GDP loss from a five-year delay represents around 1.6 per cent of EU GDP (2024: ~€17.9tn), equivalent to roughly two years of EU economic growth at the 2023-24 average pace (0.4 per cent in 2023; 1.1 per cent in 2024).[4] For an economy struggling to find growth momentum, this represents a substantial missed opportunity.

- The €344bn GDP loss is roughly twice the annual budget of the EU’s Multiannual Financial Framework.

Table 1: Economic cost of delaying the EU-Mercosur Agreement (net present value) Source: ECIPE calculations.

Source: ECIPE calculations.

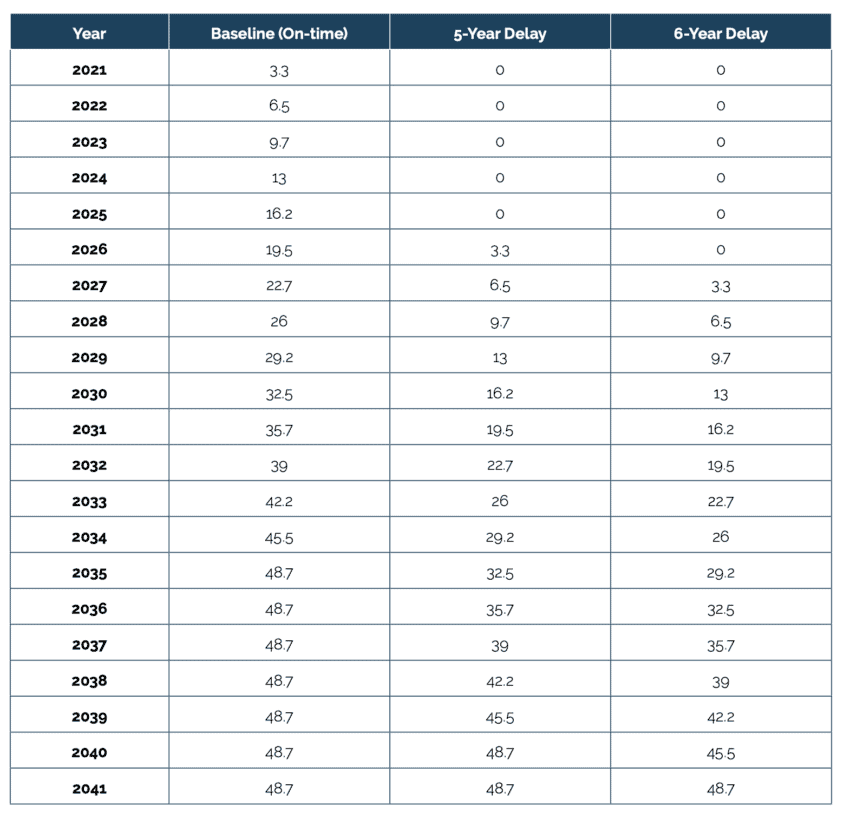

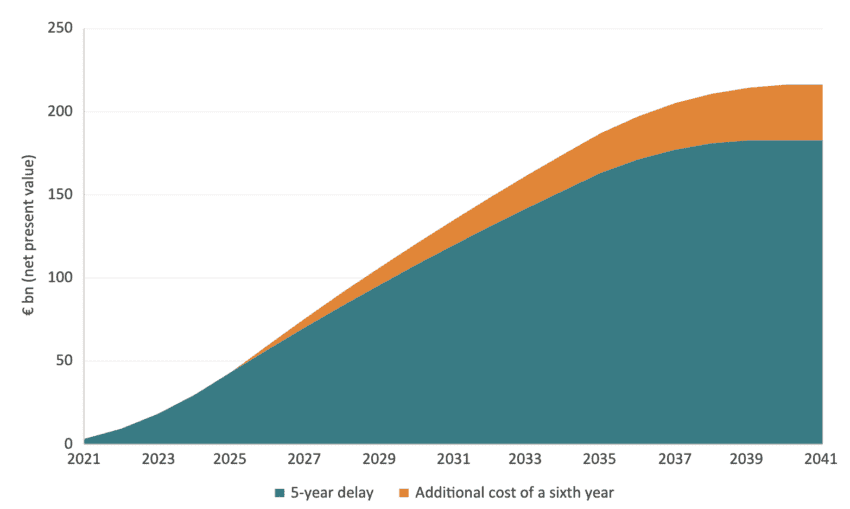

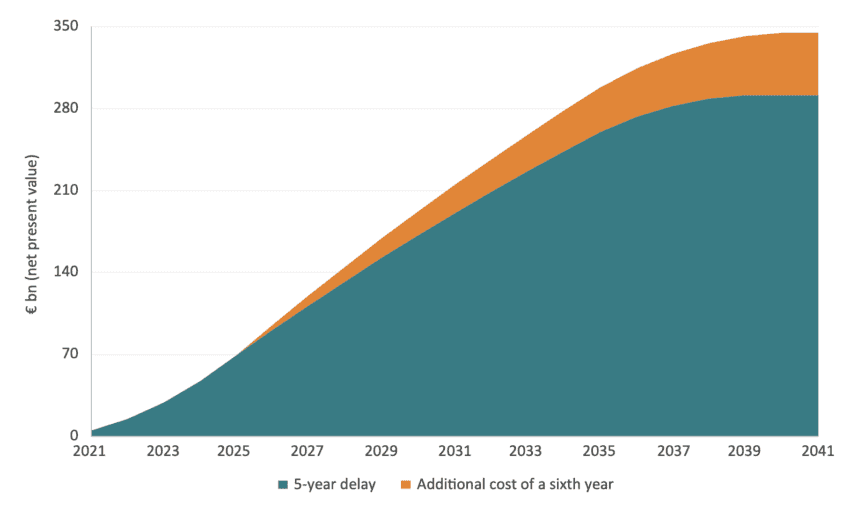

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the cumulative cost of delay, the running total of foregone exports and GDP that accumulates with each passing year. The height of the curve at any point represents the total exports (or GDP) lost up to that year compared to the case where the agreement was ratified on time in 2021. The dark blue area shows the cumulative shortfall under the five-year delay baseline – basically up to now. The light blue area shows the additional shortfall if ratification slips and the agreement cannot become effective until next year.

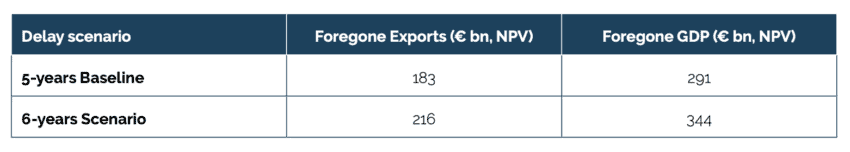

To illustrate how these cumulative costs build up, Table 2 shows the annual export gains under each scenario. In any given year, the difference between the baseline and a delay scenario represents that year’s foregone benefit. These annual gaps accumulate over time to produce the cumulative shortfalls shown in Figures 1 and 2. Once all scenarios reach full implementation (by 2041 for the 6-year delay), no new losses accrue, but the cumulative losses incurred during the delay period are permanent.

Table 2: Annual export gains by scenario (€ billion, net present value) Source: ECIPE calculations. Note: Figures represent annual export gains relative to no agreement. The baseline assumes implementation began in 2021; delayed scenarios shift the start date accordingly.

Source: ECIPE calculations. Note: Figures represent annual export gains relative to no agreement. The baseline assumes implementation began in 2021; delayed scenarios shift the start date accordingly.

Concretely, Figure 1 shows that by the end of 2021 the EU had foregone €3.2bn in exports. By the end of 2023, this number has risen to €18.2bn and, by now, the total reaches €43.7bn. The curve continues rising after ratification because the delayed scenario means the agreement needs time to catch up. The agreement still has to go through its phase in-period, so losses keep accumulating, albeit at a slower pace. By around 2040, the 5-year delayed scenario has fully caught up (phasing in complete) and no further losses are added. The final height of each curve (€183bn and €216bn for exports, €291bn and €344bn for GDP) represents the permanent cost of delay.

Figure 1: Cumulative forgone EU exports from delaying the EU-Mercosur Agreement Source: ECIPE calculations.

Source: ECIPE calculations.

Figure 2: Cumulative forgone EU GDP from delaying the EU-Mercosur Agreement Source: ECIPE calculations. Note: The GDP losses depicted incorporate both the direct impact of foregone exports and the indirect welfare gains from imports.

Source: ECIPE calculations. Note: The GDP losses depicted incorporate both the direct impact of foregone exports and the indirect welfare gains from imports.

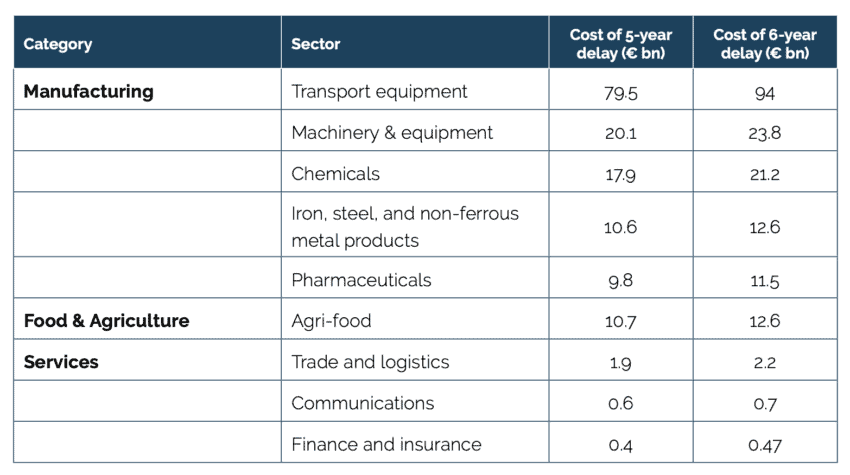

2.2 Sectoral Distribution of Missing Sales

The full economic effects of the delay will impact some economic sectors more than others. Table 3 illustrates how the missing exports are spread across key sectors (a full breakdown is provided in Table A1 of Annex I). The agri-food sector stands to lose €12.6bn under a six-year delay, especially in processed foods and beverages, sectors where Mercosur has historically maintained high barriers. Transport equipment, machinery, chemicals, iron and steel, and pharmaceuticals bear the brunt of the shortfall. For transport equipment, for example, a six-year delay would cost the sector €94bn in lost sales.

These sectors are hit hardest because they dominate EU exports to Mercosur. Machinery accounts for around 28 per cent of EU merchandise exports to the region, chemicals 25 per cent, and transport equipment a further 12 per cent. They face some of the highest remaining tariff barriers, with Mercosur import tariffs reaching nearly 20 per cent on motor vehicles and around 12 per cent on machinery. As a result, the delay in implementation disproportionately affects sectors where tariff elimination would have the largest and most immediate impact on EU export competitiveness.[5]

The delay also carries a wider competitiveness cost. The sectors most exposed to forgone exports are among the EU’s most productive and innovative. In 2023, out of twenty manufacturing sectors, pharmaceuticals and chemicals place in the top five for labour productivity, while transport equipment and machinery sit in the top ten.[6] These same sectors also lead EU business R&D investment, and the scale of forgone exports reflects this: for transport equipment, chemicals, and basic metals, the six-year delay represents lost sales equivalent to more than two years of each sector’s annual R&D budget.[7] These are precisely the high-value industries on which European economic dynamism currently depends.

The services sector also experienced forgone gains. For service providers, the delay holds back reductions in regulatory and “behind-the-border” barriers which are essential for meaningful market access.[8] For EU firms, services commitments matter because they reduce the regulatory costs of doing business, from maritime logistics to telecoms and business services. Moreover, the agreement locks in existing levels of openness and strengthens domestic-regulation disciplines, reducing uncertainty around licensing, authorisation, and market access for EU service providers. In contrast, each year of delay prolongs a period in which European firms face higher regulatory risk and less predictable operating conditions. A five-year delay represents €3bn in lost service exports, falling primarily on trade and logistics (€1.9bn), communications (€0.6bn), and financial services and insurance (€0.4bn). This aligns with the existing structure of EU-Mercosur trade; the EU is a major services exporter to the region, selling €29bn in 2023 with a persistent surplus.[9]

Table 3: Foregone EU exports across manufacturing and service sectors (net present value) Source: ECIPE calculations. Note: The table reports the sectors with the largest estimated costs of delayed implementation. Results for all remaining sectors are presented in Annex I Table A1.

Source: ECIPE calculations. Note: The table reports the sectors with the largest estimated costs of delayed implementation. Results for all remaining sectors are presented in Annex I Table A1.

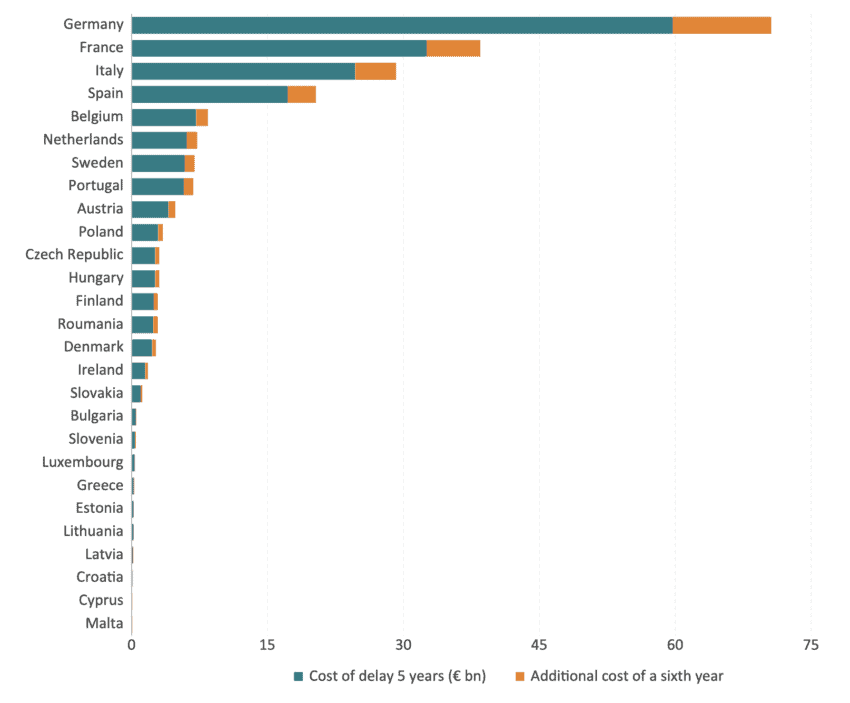

2.3 Exposure by Member State

EU countries differ in their export volumes and the sectors they trade with the Mercosur countries. To assess how EU-wide costs translate into national exposure, we distribute sector-specific losses across member states based on their export profiles to the Mercosur countries. This is calculated by weighting EU-wide losses against each country’s share of exports to Mercosur within each sector, using bilateral trade data from Purdue University’s Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) database. Crucially, this approach reflects the forgone exports across EU countries based entirely on existing trade patterns; it does not account for potential trade reallocation or the creation of new trade flows following the implementation of the agreement.

Figure 3 maps how the economic toll of delay is distributed across member states. It breaks down the total cost of a six-year delay, presenting the losses already incurred over the past five years and the additional penalty of a further twelve-month wait. Germany’s €71bn shortfall reflects its automotive and machinery dominance sectors where the agreement would have eliminated substantial tariffs. France’s €38bn loss stems heavily from transport equipment, aerospace components, and agri-food exports. Italy’s €29bn includes significant machinery, pharmaceuticals, and textile losses. For Spain, the €20bn represents not just industrial goods but also missing sales for Spanish service providers in transport, logistics, and tourism-related sectors that the agreement’s services provisions would have opened. Yet the toll is not confined to the largest countries; outward-oriented economies like Belgium and the Netherlands face significant losses of roughly €8bn and €7bn respectively. Similarly, Sweden, Portugal, and Austria suffer substantial missing export sales.

To put these figures in perspective: for France and Italy, the six-year delay represents forgone exports equivalent to roughly one and 1.6 years of economic growth, respectively, in 2023 and 2024.[10] For Germany, where the economy contracted in both 2023 and 2024, the €71bn shortfall amounts to 1.7 per cent of GDP, incurred during a period when growth was negative.

Figure 3: Foregone EU exports across member states (€ bn, NPV) Source: ECIPE calculations.

Source: ECIPE calculations.

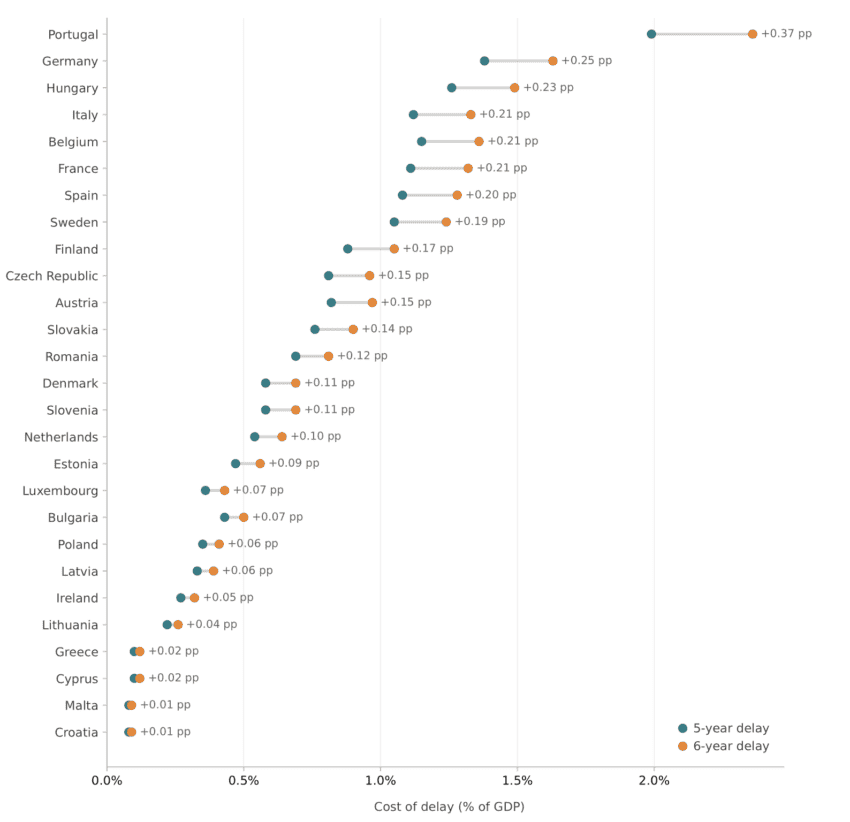

The net present value of these forgone exports represents a significant share of EU member states’ GDP today. Figure 4 illustrates export losses as a proportion of each member state’s GDP,[11] alongside the additional missing exports – expressed in additional percentage points between the 5 and the 6-year delay – of postponing ratification by another year. Across a broad range of member states, including Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Hungary, Belgium, Sweden, and Finland, the cumulative export shortfall of a six-year delay is projected to be the equivalent of 1 to 1.75 per cent of GDP.

Figure 4: Foregone EU exports across member states (NPV, percentage of GDP) Source: ECIPE calculations.

Source: ECIPE calculations.

2.4 Other Problems Caused by Delayed Ratification

There are other costs of delay. When trade policy remains ambiguous, firms tend to reallocate resources towards jurisdictions offering greater certainty. For example, a European automotive supplier considering an investment in a factory in Argentina faces a choice: wait for a ratification that may never materialise or divert that capital to a market such as Mexico or Vietnam, where market access is assured with FTAs. In this case, the ‘cost of delay’ is no longer limited to trade diversion but extends to a reorientation of supply chains. Once a factory is built in Vietnam, it does not relocate to Mercosur simply because the EU decides to ratify the EU-Mercosur Agreement.

This is crucial. Modern trade agreements do more than lower tariffs: they also influence where firms place production, how they organise value chains, and whether they scale up investment. Evidence on so-called ‘deep’ trade agreements shows that, beyond tariffs, provisions that reduce trade costs and uncertainty can strengthen participation in global value chains and encourage more integrated cross-border production. These effects are particularly relevant for high-value manufacturing and the business services that support it,[12] which – as we saw previously – stand to benefit the most from the EU-Mercosur Agreement.

Delaying implementation therefore weakens the EU’s competitive position not only by keeping border barriers in place, but also by postponing the critical “investment moment” when firms decide whether to commit to a market. This matters in a geoeconomic environment where supply-chain security and predictability have become policy objectives in their own right. Critical Raw Materials (CRMs) provide a clear example. In recent years, China has actively used its dominant market position to apply political pressure on other countries, including the EU, to advance its goals. As a result, the EU has adopted policies and regulations such as the Critical Raw Materials Act to support diversification away from China in these goods. The EU-Mercosur Agreement is a key component of this strategy. Argentina and Brazil are important suppliers for lithium, copper, and other raw materials central to Europe’s green and digital transitions.[13] Yet European firms operating in Mercosur sometimes face export restrictions, regulatory opacity, and policy volatility. The EU-Mercosur Agreement would help address these frictions by disciplining, and in some cases eliminating, export duties, strengthening transparency, and improving legal certainty for long-term investment. By delaying ratification, however, the EU constrains its own supply-chain diversification and reinforce its dependency on Chinese raw materials.

[1] European Commission. (2019, June 28). EU and Mercosur reach agreement on trade. Press release. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_19_3396

[2] A detailed methodology and data sources can be found in the Annexes.

[3] European Commission, Directorate-General for Trade. (2025). Economic analysis of the negotiated outcome of the EU–Mercosur Partnership Agreement (Publication No. NG0125012ENN). Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2781/1755921

[4] Eurostat (2025). Gross domestic product (GDP) and main components (output, expenditure and income). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/NAMA_10_GDP

[5] European Commission, Directorate-General for Trade. (2025). Economic analysis of the negotiated outcome of the EU–Mercosur Partnership Agreement (Publication No. NG0125012ENN). Publications Office of the European Union. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/6f1a741f-677e-11f0-bf4e-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

[6] Eurostat. (2025). Structural business statistics: Overview. https://doi.org/10.2908/SBS_SC_OVW

[7] Eurostat (2025). Business enterprise R&D expenditure (BERD) by NACE Rev. 2 activity, 2023. https://doi.org/10.2908/RD_E_BERDINDR2. Annual R&D investment: transport equipment €43.8bn, machinery €29.1bn, pharmaceuticals €18.8bn, chemicals €10.7bn, iron, steel, and metals €5.9bn.

[8] Azomahou, T. T., Maemir, H., & Wako, H. A. (2021). Contractual frictions and margins of trade. Journal of Comparative Economics, 49(4), 1048-1067. Hoekman, B. M. (2018). “Behind-the-Border” regulatory policies and trade agreements. East Asian economic review, 22(3), 243-273.

[9] Ibid

[10] Calculated using average GDP growth in 2023-24: France 1.3 per cent (1.4 per cent in 2023, 1.2 per cent in 2024), Italy 0.85 per cent (1.0 per cent in 2023, 0.7 per cent in 2024), Germany -0.7 per cent (-0.9 per cent in 2023, -0.5 per cent in 2024). Source: Eurostat, GDP and main components (NAMA_10_GDP).

[11] Eurostat (2025). Gross domestic product (GDP) and main components (output, expenditure, and income). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/NAMA_10_GDP

[12] Laget, E., Osnago, A., Rocha, N., & Ruta, M. (2020). Deep trade agreements and global value chains. Review of Industrial Organization, 57(2), 379-410.

[13] Guinea, O., & Sharma, V. (2023). European Economic Security and Access to Critical Raw Materials: Trade, Diversification, and the Role of Mercosur. ECIPE, Brussels, Policy Brief 9/2023, 28 p.

3. Conclusion

Time is money. Delaying the ratification of the EU-Mercosur Agreement has certainly not been a cost-free option. Since the agreement was effectively concluded in 2019, and should have been in operation by 2021, the EU has forgone a massive volume of trade and economic growth. Every year that ratification is deferred pushes the realisation of these gains further into the future, reducing the value of the agreement to European industry and citizens.

This analysis has quantified the ‘missing trade’ since the agreement was finalised for the EU, across economic sectors and EU member states. The methodology has been to calculate the net present value of the gains of the agreement, once it has been implemented in full. The results are striking:

Overall Economic Impact: the five-year delay (2021-2025) has already cost the EU an estimated €183bn in forgone exports and €291bn in gross domestic product. This represents, in today’s terms, 1.6 per cent of the EU’s total economic output and is equivalent to approximately two years of European economic growth at the rates observed in 2023 and 2024. Should the agreement remain unratified through 2026, these losses are projected to climb to €216bn in exports and €344bn in GDP. The cumulative export shortfall would exceed the EU’s entire annual merchandise exports to Switzerland, the EU’s fourth-largest trading partner. Every additional month of delay during 2026 imposes costs of approximately €4.4bn in foregone GDP and €3bn in missing exports.

Sectoral Losses: the unrealised sales are concentrated in the EU’s manufacturing sector and amount to billions of euros. The transport equipment industry faces a potential shortfall of €94bn in the scenario of a six-year delay; machinery and equipment (€23.8bn), chemicals (€21.2bn), iron and steel and agri-food (€12.6bn each), and pharmaceuticals (€11.5bn). Firms within these industries rank among the EU’s most productive and innovative. Therefore, the missing sales from the delayed ratification of the agreement are harming EU’s competitiveness. For transport equipment, chemicals, and basic metals, the six-year delay represents lost sales equivalent to more than two years of each sector’s annual research and development budget. The services sector has also incurred significant forgone exports, reaching €3bn, primarily in trade and logistics (€1.9bn), communications (€0.6bn), and financial services (€0.4bn). These are precisely the high-value industries on which European economic dynamism currently depends.

Country Impacts: Germany faces the largest absolute loss at €71bn in forgone exports in the scenario of a six-year delay, which is equivalent to 1.7 per cent of GDP in 2023 and 2024. France experiences €38bn in foregone exports (approximately one year of economic growth), while Italy loses €29bn (roughly 1.6 years of growth). Spain faces €20bn in losses. However, the economic pain is not confined to these countries. Every EU economy suffers from the delay in the ratification of the agreement. For export-oriented economies like Portugal, Hungary, Belgium, and Sweden, the cumulative export shortfall is, in today’s terms, equal to more than 1 per cent of their national GDP.

Supply-Chain Resilience: by postponing ratification, the EU constrains its own supply-chain diversification and reinforces its vulnerability to Chinese market dominance, particularly in critical raw materials. Faced with policy uncertainty regarding Mercosur market access, European firms redirect capital in alternative jurisdictions, where market access is assured. As European firms withdraw or fail to expand their presence in Mercosur, competitors – particularly China – consolidate their market positions and supply-chain links in the region. The result is a decline in Europe’s economic footprint and political influence in the Mercosur countries.

The evidence presented in this Policy Brief demonstrates that the opportunity cost of continued delaying the ratification of the EU-Mercosur Agreement substantially exceeds any remaining policy concerns. Swift ratification of the agreement is an imperative for European economic growth, competitiveness, and economic resilience.

References

Azomahou, T. T., Maemir, H., & Wako, H. A. (2021). Contractual frictions and margins of trade. Journal of Comparative Economics, 49(4), 1048-1067.

European Commission (2019, June 28). EU and Mercosur reach agreement on trade. Press release. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_19_3396

European Commission (2025). Economic analysis of the negotiated outcome of the EU-Mercosur partnership agreement (EMPA). Publications Office of the European Union. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/6f1a741f-677e-11f0-bf4e-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

Eurostat (2025). Business enterprise R&D expenditure (BERD) by NACE Rev. 2 activity, 2023. https://doi.org/10.2908/RD_E_BERDINDR2

Eurostat (2025). Gross domestic product (GDP) and main components (output, expenditure and income). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/NAMA_10_GDP

Eurostat (2025). Structural business statistics: Overview. https://doi.org/10.2908/SBS_SC_OVW

Guinea, O., & Sharma, V. (2023). European Economic Security and Access to Critical Raw Materials: Trade, Diversification, and the Role of Mercosur. ECIPE, Brussels, Policy Brief 9/2023, p. 28.

Hoekman, B. M. (2018). “Behind-the-Border” regulatory policies and trade agreements. East Asian economic review, 22(3), 243-273.

Laget, E., Osnago, A., Rocha, N., & Ruta, M. (2020). Deep trade agreements and global value chains. Review of Industrial Organization, 57(2), pp. 379-410.