Published

A New Era in Global Trade: The EU–India Free Trade Agreement

By: Koen Berden

Research Areas: EU Single Market, Institutions, and Governance Trade, Globalisation and Security

On 26 January 2026, the European Union and India formally concluded negotiations on one of the most significant trade pacts in recent history in terms of GDP and share of the global population. According to Von der Leyen: “In this increasingly volatile world, Europe chooses cooperation and strategic partnerships. Today, we have signed the EU-India Free Trade Agreement – the mother of all trade deals”.[1] With the conclusion of the EU-India FTA, relations between the EU and India enter a new phase. The long-anticipated Agreement arrives at a pivotal moment in global international relations: a period defined by rising protectionism, supply-chain reconfigurations, and tariff frictions. But while some hail the Agreement as the ‘mother of all trade deals’ others claim it is not an ambitious deal, with limited liberalisation only, focused on non-sensitive sectors, wrapped up for political reasons.

This insight looks into the following policy questions: What is the economic and geopolitical value of the recently concluded EU-India Free Trade Agreement (FTA)? Is it really ‘the mother of all trade deals’ or just a political statement in a time of geopolitical uncertainty?

Negotiating Timeline for the EU–India FTA

Negotiations for the EU-India FTA started 20 years ago and can be split into the 2007 – 2013 and the 2022 – 2026 periods.

First negotiation phase (2007 – 2013)

The first negotiation phase (2007 – 2013) started in 2004 when the EU and India established a Strategic Partnership. In 2006, the EU and India agreed to launch negotiations towards a Broad-based Trade and Investment Agreement (BTIA). They commenced in 2007. From 2008 – 2009, the first Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA) was carried out, published in May 2009 (by Ecorys, CUTS and CENTAD), looking at the potential economic, social, and environmental impact of a BTIA.[2] From 2007 to 2013, negotiations continued through multiple rounds, but no agreement was reached due to persistent differences between the Parties on tariffs, services, intellectual property (IP), agriculture, and investment. Talks were effectively suspended in 2013 (without a formal conclusion).

Second negotiation phase (2022 – 2026)

After an interim period (2013 – 2021) where no active negotiations took place, both sides reassessed their trade strategies amid global economic and geopolitical shifts and in May 2021, EU and Indian leaders agreed to relaunch FTA negotiations through three separate frameworks: a trade agreement, an investment agreement, and a geographical indications agreement. In June 2022, negotiations resumed along these lines. In 2023, a new SIA was conducted (by Trade Impact) and published in February 2024.[3] Throughout 2024 and 2025, multiple negotiation rounds took place, and several chapters on goods, services, IP and customs were concluded. Following a high-level meeting between the EU and India, negotiations intensified from February 2025 onwards. On 27 January 2026 a the negotiations were concluded and a deal was announced by European Commission President Von der Leyen, European Council President Costa and Indian Prime Minister Modi, at the high-level EU-India Summit in New Delhi.

Content of the EU–India Free Trade Agreement

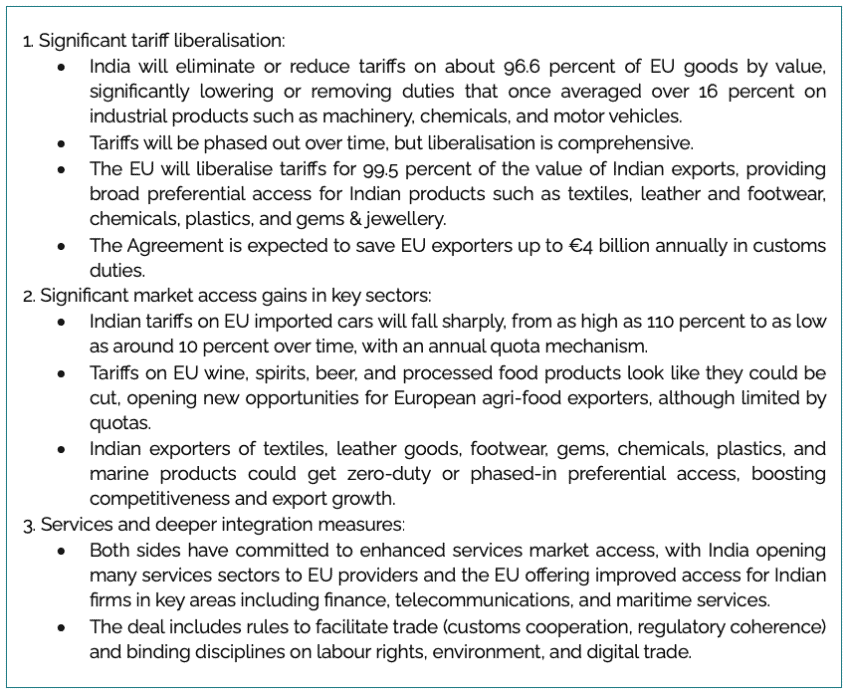

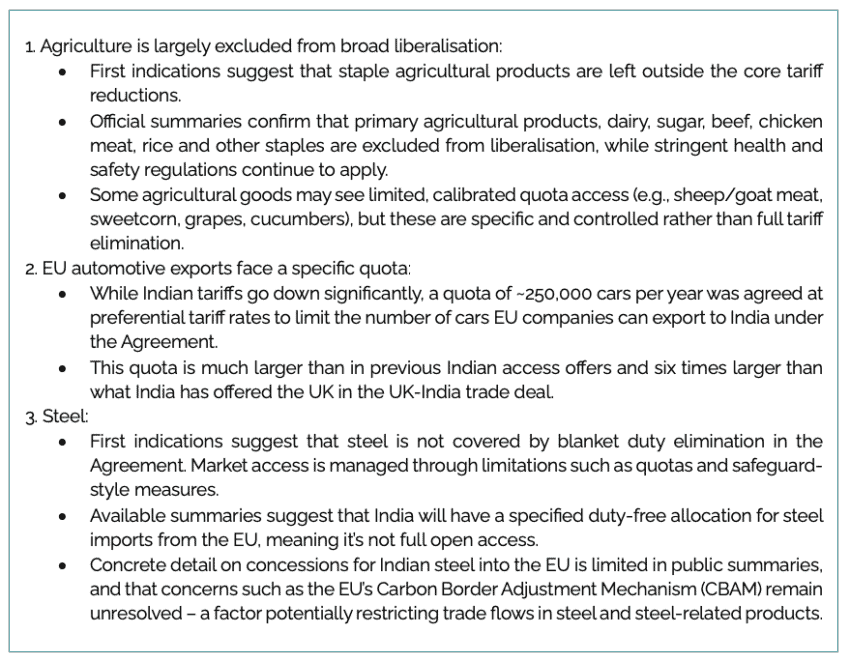

The question of whether this EU-India FTA is an ambitious one or not cannot be answered in full detail at this stage, because the exact provisions that have been agreed are not yet known, because the negotiated draft text still has to undergo legal revision, translation and internal approval procedures before formal publication and signature. While a final verdict on the level of ambition of the EU-India FTA is still not fully possible, based on summaries, chapter outlines and press statements known to date, it is possible to make a first analysis and share relevant insights.[4] The negotiated EU-India FTA looks like it is comprehensive in nature, but does also contain a few significant carve-outs where liberalisation is less ambitious or limited. Table 1 and Table 2 highlight the key aspects of the negotiated FTA known to date.[5] [6] [7]

Table 1: Ambitious elements in the EU-India FTA

Table 2: More limited trade liberalisation elements in the EU-India FTA So, while it looks like market access is significantly enhanced overall, sensitive agricultural products (e.g., dairy, rice, beef, sugar) seem to remain excluded and/or subject to safeguard/quota provisions to protect domestic producers on both sides. The deal maintains public health and safety standards (e.g. EU sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) and food-safety rules) to prevent disruptive import surges while expanding opportunities for specific processed products. The argument that geographical indications (Gis) are not included in the Agreement is correct, but that is because a separate GI agreement is still being negotiated in parallel to this FTA. As a result, the EU-India FTA seems to deliver on ambitious tariff liberalisations for goods, services access, regulatory cooperation, and strategic economic integration between two major global markets, while balancing domestic sensitivities, especially in agriculture through significantly lower levels of market access commitments both ways.

So, while it looks like market access is significantly enhanced overall, sensitive agricultural products (e.g., dairy, rice, beef, sugar) seem to remain excluded and/or subject to safeguard/quota provisions to protect domestic producers on both sides. The deal maintains public health and safety standards (e.g. EU sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) and food-safety rules) to prevent disruptive import surges while expanding opportunities for specific processed products. The argument that geographical indications (Gis) are not included in the Agreement is correct, but that is because a separate GI agreement is still being negotiated in parallel to this FTA. As a result, the EU-India FTA seems to deliver on ambitious tariff liberalisations for goods, services access, regulatory cooperation, and strategic economic integration between two major global markets, while balancing domestic sensitivities, especially in agriculture through significantly lower levels of market access commitments both ways.

Free Trade Agreement Benefits: Broad and Sector-Specific Gains

The conclusion of the negotiations is a key step, but ratification will need to follow. The Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA) of 2024 provides a rare degree of quantitative clarity on what industry could stand to gain from the EU-India FTA.[8] The view that this Agreement is merely a political statement does not seem to match with the aspects on the content of the FTA that have become public so far. The ex-ante Trade SIA has looked at moderate and ambitious scenarios. The currently agreed FTA seems to have most aspects in common with the ambitious liberalisation scenario, with some moderate elements as well (e.g. on agriculture, steel). The findings of the SIA confirm that the Agreement is economically meaningful for both sides. In Politico’s reporting on the conclusion of negotiations[9], EU trade officials highlight that services – including telecoms, maritime, and financial services – are expected to benefit from expanded cooperation under the Agreement, marking a strategic shift in India’s openness to new forms of economic engagement. For India, the Agreement supports its objective of greater integration into EU value chains via reduced tariffs and NTMs, improving market access for textiles, wearing & apparel and services industries.

For the EU, the SIA estimates that:

- Bilateral EU exports to India increase by 107.6 percent by 2032 because of an ambitious FTA.

- The largest market access (export) gains accrue to chemicals (€21.7 billion), machinery (€17.2 billion), electronics and electrical equipment (€17.5 billion), and pharmaceuticals (€3.3 billion).

- Transport equipment, including motor vehicles and parts, sees EU exports rise by 188 percent (€6.6 billion), reflecting the combined impact of tariff reductions and regulatory cooperation in automotive standards, a welcome boost to the EU automotive industry’s competitiveness.

- Overall EU GDP increases by €47.9 billion (+0.2 percent), while welfare gains reach €41 billion, indicating that export growth translates into broader macroeconomic benefits for EU citizens rather than only sector-specific windfalls.

- Real wages rise marginally for both skilled (+0.1 percent) and unskilled workers (+0.2 percent) in the EU, showing that the Agreement has a small positive distributional effect for the EU.

- In manufacturing sectors such as machinery, electronics, chemicals, and motor vehicles, NTM liberalisation accounts for the majority of export growth, confirming industry views that regulatory frictions, rather than tariffs, have been the principal constraint on access to the Indian market.

- Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) stand to benefit disproportionately. The SIA notes that over 70 percent of EU firms exporting to India are SMEs, and projects strong export growth in SME-intensive sectors such as machinery, metal products, rubber and plastics, paper, and leather.

For India, the SIA finds similarly robust outcomes:

- India’s bilateral exports to the EU rise by 86.6 percent under the ambitious EU-India FTA.

- The strongest gains occur in wearing apparel (€24 billion), chemicals (€16.3 billion), textiles (€8.4 billion), and leather (€5.3 billion), confirming the Agreement’s importance for labour-intensive manufacturing.

- India’s GDP increases by €69.6 billion (+1.0 percent), while welfare gains amount to €33.8 billion, driven by higher trade volumes and productivity effects, even with decreased tariff revenues.

- Real wages rise for both skilled (+0.6 percent) and unskilled workers (+1.3 percent), underscoring the Agreement’s distributional benefits within the Indian economy.

Notably, the SIA finds that no major sector in either the EU or India experiences a decline in bilateral exports as a result of the Agreement. While some sectors face output reallocation pressures domestically, the overall trade effect is strongly positive and complementary, rather than zero-sum. Taken together, the quantitative evidence from the SIA confirms that the EU-India FTA is not a marginal trade deal.

Strategic Imperatives in a Fragmented Global Economy

In addition to the economic aspects of the concluded EU-India FTA, this Agreement must also – or should maybe even more so – be seen through the lens of a shifting geopolitical and economic order. EU-India negotiations started almost 20 years ago, but more recent geopolitical shifts have likely helped this bilateral over the finish line. Trade relations among the world’s largest economies are experiencing turbulence. The EU and US have clashed over tariffs, green industrial subsidies[10], and regulatory approaches, while the EU has put countervailing duties on BEVs from China[11], is challenging IP policies and has put several Chinese and Hong Kong entities in EU sanctions packages for supporting Russia’s military-industrial base.[12] India, in turn, has faced US import tariffs of up to 50 percent on a range of goods, faces a trade deficit with China and is not participating in integration in the Indo-Pacific (e.g. in RCEP – the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership).[13] [14] This has reinforced both the EU’s and India’s resolve to diversify trade partnerships strategically.

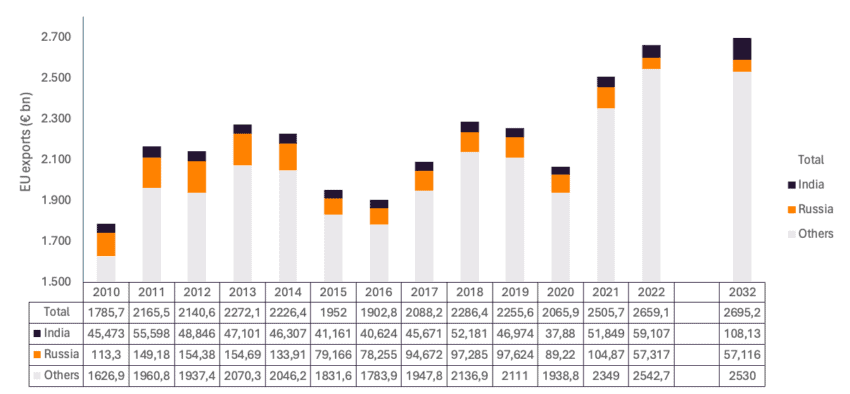

For the EU, the Agreement, that eliminates most tariffs and reduces NTMs, reinforces a policy of “open strategic autonomy.”[15] Rather than depending on a very small number of major partners for market access or supply-chain integration, the EU is cementing ties with other trading partners like Canada, Japan, Vietnam, Mercosur, and now also India; with India being the world’s fastest-growing major economy. The FTA broadens market access for EU exporters and lessens dependency on markets where tariffs are rising and markets where sanctions have blocked market access for EU firms. As an example, Figure 1 shows how EU exports to Russia have dropped from €105 billion in 2021 to €57 billion in 2022 (dropping further in 2023) as a result of the sanctions, while EU exports to India are expected to increase from €59 billion in 2022 to €108 billion in 2032 with an EU-India FTA. This is evidence that the FTA does act as an alternative outlet for EU companies, offsetting some of the losses incurred by blocked access to Russia after February 2022.

Figure 1: EU exports to India, Russia and all other countries (2010 – 2022, € billion) Source: Ruda et al. (2023)

Source: Ruda et al. (2023)

For India, the Agreement, through substantive duty elimination, accelerates diversification away from heavy reliance on China and the US, directly countering tariff and regulatory risk by anchoring India more deeply in global value chains with the EU, already one of its top trading partners. It also offers Indian firms market access opportunities as an alternative to the Indo-Pacific. In addition to an FTA with the EU, India – in February 2026 – also agreed on a framework with the US to address reciprocal tariffs – with more work ahead towards a full trade agreement.[16]

Indeed, the SIA also finds that the Agreement supports EU supply-chain diversification and resilience objectives, identifying India as a key partner for reducing over-concentration risks in critical sectors such as chemicals, pharmaceuticals, machinery, electronics, and transport equipment.[17] More in general, there is no doubt that this FTA and its timing, will have a geopolitically stabilising effect amid rising protectionism and strategic competition; a win for global rules-based trade.

Conclusion: The EU–India FTA Is a Win-Win for the Global Trade Order

The EU-India Free Trade Agreement is not just a political statement; it represents a milestone in 21st-century trade governance. It seems to be comprehensive in nature, but does also contain several carve-outs where liberalisation is limited (e.g. agriculture). As a result, the FTA appears to be closer to the ambitious than the modest scenario of the SIA. The ambitious scenario indicates that economic gains are likely to be significant. EU exports to India could increase by triple digits. Significant market access improvements for EU exporters are negotiated for chemicals, machinery, electronics and electrical equipment, motor vehicles and pharmaceuticals while Indian wearing apparel, chemicals, textiles and leather exporters also gain significantly. EU and Indian GDP stand to gain each year, real wages in both Parties go up, and SMEs are expected to benefit disproportionally.

But the FTA goes beyond simple tariff liberalisation, having strategic and geopolitical impact too. At a time when tariff tensions are at an 80-year high, structural pressures in global supply chains persist, current US and Chinese market pressures are increasing, and the rules-based trading system is under attack, this Agreement provides both the EU and India with increased levels of strategic economic insurance while reinforcing global trade norms. For the EU, the EU-India FTA, in combination with many other EU FTAs (e.g. with Canada, Singapore, Japan, Vietnam, Mercosur) forms a strong foundation of FTAs that: 1) support open strategic autonomy; 2) reduce dependencies on a very narrow number of large trading partners; 3) create a predictable environment of rules for EU companies to conduct their trade and investments; and 4) position the EU as a pivotal player in the Indo-Pacific. For India, this Agreement with the EU is another engine for growth and global value chain integration with a top-trading partner, essential for the Indian economy. For India the FTA completes a significant list of recently concluded Agreements with EFTA, the UK, New Zealand and Oman, while talks for an agreement with the US are ongoing. For India this FTA clearly offsets some of the relative losses in market access for Indian firms in Asian markets as a result of India not being a Party to RCEP.

If implemented effectively, this Agreement could act as a platform to build trust to enhance industrial cooperation, deepen regulatory dialogues, and promote inclusive growth at the heart of bilateral economic engagement. These effects, in turn, could help further deepen the EU-India relationship also in other key areas like security & defence, security information, critical technologies, innovation & research, clean energy & investment, global gateway green shipping corridors, and worker mobility – as part of the already endorsed “Towards 2030: EU-India Joint Comprehensive Strategic Agenda”.[18]

[1] European Commission (2026), “16th EU-India Summit: advancing our Strategic Partnership across trade and defence”, 27th of January 2026. URL: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_26_227

[2] Berden, K., F. Smakman, N. Plaisier and J. Francois (2009) “Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment for the FTA between the EU and the Republic of India”, February 2009. URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303297797_Trade_Sustainability_Impact_Assessment_for_the_FTA_between_the_EU_and_the_Republic_of_India

[3] Ruda, M., K. Berden, T. Berden-Antonenko, D. Bienen, and A. Oger (2023) “Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA) in support of Free Trade Agreement and Investment Protection Agreement negotiations between the European Union and the Republic of India”, Trade Impact BV study for DG Trade, December 2023, URL: https://www.eu-india-tsia.eu/resources

[4] European Commission (2026), “EU-India Agreement: documents”, URL: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/india/eu-india-agreements/documents_en

[5] Financial Times (2026), “EU and India seal trade pact to slash €4 bn of tariffs on bloc’s exports”, 27 January 2026. URL: https://www.ft.com/content/b03b1344-7e92-4d0d-b85e-5ed92fc8f550

[6] Reuters (2026), “India, EU reach landmark trade deal, tariffs to be slashed on most goods”, 27 January 2026, URL: https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/india-eu-slash-tariffs-autos-spirits-textile-landmark-deal-2026-01-27/

[7] Politico (2026), “EU, India reach agreement on trade deal”, 26 January 2026. URL: https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-india-trade-agreement-deal-telecoms-finance/

[8] Ruda, M., K. Berden, T. Berden-Antonenko, D. Bienen, and A. Oger (2023) “Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA) in support of Free Trade Agreement and Investment Protection Agreement negotiations between the European Union and the Republic of India”, Trade Impact BV study for DG Trade, December 2023, URL: https://www.eu-india-tsia.eu/resources

[9] Politico (2026), “EU, India reach agreement on trade deal”, 26 January 2026. URL: https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-india-trade-agreement-deal-telecoms-finance/

[10] Politico (2026), “EU faces up to US green subsidies with industrial overhaul”, 1 February 2023, URL: https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-faces-up-to-us-green-subsidies-with-industrial-overhaul/

[11] European Commission (2024), “EU imposes duties on unfairly subsidised electric vehicles from China while discussions on price undertakings continue”, 29 October 2024. URL: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_5589

[12] Politico (2025), “EU hammers Putin and charms Trump by targeting China, India in new Russia sanctions”, 19 September 2025, URL: https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-commission-approves-new-russia-sanctions-package-to-hit-putins-war-chest/

[13] CNBC.com (2024), “India rules out joining RCEP accuses China of non-transparent trade practices”, 23 September 2024, URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2024/09/23/india-rules-out-joining-rcep-accuses-china-of-non-transparent-trade-practices.html

[14] NDTV.com (2026), “Nothing on the table: India says it is not joining China backed trade pact”, 4 February 2026. URL: https://www.ndtv.com/world-news/nothing-on-the-table-india-says-it-is-not-joining-china-backed-trade-pact-10902365

[15] Financial Times (2026), “EU and India seal trade pact to slash €4 bn of tariffs on bloc’s exports”, 27 January 2026. URL: https://www.ft.com/content/b03b1344-7e92-4d0d-b85e-5ed92fc8f550?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[16] The Diplomat (2026), “Did Trump jump the gun with the US-India trade deal?”, January 2026. URL: https://thediplomat.com/2026/02/did-trump-jump-the-gun-with-the-us-india-trade-deal-announcement/

[17] Ruda, M., K. Berden, T. Berden-Antonenko, D. Bienen, and A. Oger (2023) “Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA) in support of Free Trade Agreement and Investment Protection Agreement negotiations between the European Union and the Republic of India”, Trade Impact BV study for DG Trade, December 2023, URL: https://www.eu-india-tsia.eu/resources

[18] European Commission (2026), “Towards 2030: A Joint European Union-India Comprehensive Strategic Agenda”, 27th of January 2026. URL: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_26_224